Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (39 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

From their offices down on Lafayette Street, the city planners were saying it just couldn’t be—that so topsy-turvy a mix of new and old,

residential and grittily industrial, charming and unlovely,

necessarily

made for a slum. To prove the contrary, Jane and her neighbors invited journalists and others to visit West Villagers in their homes. However awful the neighborhood was supposed to be, went the strategy, it wouldn’t square with what you’d see right in front of your nose. A building at 661 Washington Street? Well, yes, a bit run-down—yet with clean hallways, tidy apartments. The borough president came through in March and, according to a

New York Times

reporter, was “impressed by the

generally high standards of the living quarters he saw within outwardly shabby buildings,” and “by the intensity of feeling among tenants who were clearly not slum dwellers.”

“During the West Village neighborhood fight, we had a penny sale at St. Luke’s Church,” Jane wrote of this photo. “Penny sales were not part of the Anglican tradition, but they were a part of the Catholic tradition in the neighborhood, so they ran the sale and St. Luke’s gave the space. This was the first ecumenical thing I know of that had ever occurred in the area. It was a great success.”

Credit 22

During March, the West Village committee

surveyed all fourteen blocks in the threatened area, systematically reporting on renovations made to homes in recent years: A new roof at 739 Greenwich in 1951, new wiring in 1953, new bathrooms in 1956. At Jane’s neighbors’ at 561 Hudson, new plumbing and oil burner, windows repaired, new paint inside and out, new kitchen fixtures. Over on West Eleventh, a whole row of houses completely renovated. At 115 Perry, the halls painted the previous year, along with new pipes, plumbing, and windows. Page after

page it went on like this. As for West Village businesses, 140 of them, they included a uniform maker, a dance studio, a bookstore, a cabinet maker, a motor scooter shop, a clothing store, a locksmith, a tax consultant, bars, sculptors, artists, printers, importers. They employed 1,950 men and women. If the cheek-by-jowl quality of homes and businesses in the West Village’s twentieth of a square mile was supposed to be so bad, virtually the definition of blight, it didn’t come out that way in the survey.

In late April, the committee distributed a letter to the planning commission by two members of the Municipal Art Society’s Historic Architecture Committee. “The 14-block area of West Greenwich Village that has been proposed for urban renewal,” these experts led off, “is

fundamentally as attractive as other portions of Greenwich Village, and in some ways more unusual in much of its architecture,” some of which dated to the early 1800s, when a section of it was a river landing. They referred to its “waterfront town architecture”; pointed up “a rare group of early workaday structures” on Greenwich and West Eleventh; Greek Revival interiors on Charles Street; some bright, many-windowed tenements that showed off a “surprising exuberance of decorative masonry treatment.” This was 1961, before the demolition of Penn Station had sparked the historic preservation movement, but the writers were anticipating what today is called “adaptive re-use”: some “inherently messy or unattractive [uses], such as paper baling, exist like hermit crabs in buildings which might quite easily be put to other uses—and if the natural history of the structures is not cut short by urban renewal,” they added, “undoubtedly will be.”

Much the same, different in detail but identical in principle, could have been said of East Harlem before the projects went up, or of Boston’s West End before it was razed. This time it was being said

before

the damage was done.

Bruno Zevi, a distinguished Italian architect, historian, and former Village resident, author of an influential book called

Towards an Organic Architecture

, weighed in: “I have

no romantic attitude toward slums,” but no part of Greenwich Village, he declared, was a slum. Cities, he went on, had a “natural texture” that needed respect; to tamper with it was to destroy it.

In a community such as the west Village, where residential and industrial uses are mixed, one can never know if the community has created its own pattern and architecture, or if the architecture creates the community. Where the result is admirable, as it is in the west Village—that is, where integration is complete and viable—it should not be questioned. Yet I understand that your city planners have stated that they will segregate residential and non-residential uses. What can be considered bad about industry if it does not pollute the air and soil of the community?

Save the West Village’s campaign was a relentlessly negative one—by design. It said

No.

It asked for nothing but a reversal of the city’s plans. It sought no compromise.

The West Village was no slum, went its drumbeat of a message. Don’t mess with it.

No slum; block its designation as one.

No slum; don’t let urban renewal get its mitts on it.

This tack, Jane would explain, had its roots in their group’s efforts to bring influential outsiders to the neighborhood. One was a federal housing official whose tour of the West Village surprised him with its range of incomes and convinced him it was not a slum. Along the way he bestowed on Jane what became a central tenet of their strategy—a “secret” she’d reveal numerous times over the years: “Never ever tell anyone in state or city government what you want for improvements because then you’re considered a ‘participating citizen.’ Then they can say they have citizen participation and do whatever they want. He told us not to be afraid of being considered ‘merely negative.’ ” And

that

, to the endless annoyance of city officials, was exactly what they were: first overturn that damning slum designation, went the idea. Only then come back with positive and constructive plans—which, as we’ll see, is just what Citizen Jane and her friends later did.

“We’ve had to become experts in everything from how to run torchlight parades to how to analyze typewriter type and collect legal evidence,” Jane wrote while in the thick of the fight. At one point they sent an audio engineer around town to

record sound levels; of course, he found the West Village quieter, presumably more peaceful, than some of New York’s tonier districts. Pierre Tonachel, a young lawyer enlisted early in the fight, remembers Jane saying of their opponents, “You have to make them feel they’re being

nibbled to death by ducks.” Fresh out of Cornell, Tonachel was living in a nineteenth-century house on a busy block of Bethune Street not far from Jane’s place when he was introduced to her.

Inside of fifteen minutes, he concluded that he stood in the presence of some odd breed of genius. She was smart, but much more. She

always

knew what she was talking about. She possessed capacious warmth yet, faced with duplicity or stupidity, could express withering contempt. “She didn’t suffer fools gladly,” Tonachel says. “She got impatient with drivel.” Under Jane’s leadership, it seemed to him, the West Village war was being waged not by some ragtag community militia but by real pros; everything was more professional than it had any right to be. Even “the quality of the paperwork” the committee put out, he marvels, “was stunning; Jane inspired that.”

Another veteran of the West Village, Nate Silver, who met Jane in November 1961, would conjure up a bad movie of those years, down to “

an action-packed montage of calendar pages flipping,” people marching with placards, fund-raising parties, “now a medium shot of Jane Jacobs speaking at a public hearing in the balustraded Old-Bailey-style municipal council chamber of New York and the shot should take in Italian laps with babies, black faces, defensive-looking city officials.”

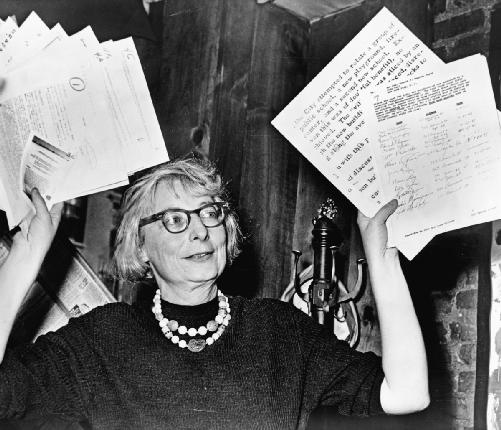

Jane, as chairman of the Committee to Save the West Village, presents evidence at a press conference at the Lion’s Head restaurant, New York, 1961.

Credit 23

A public meeting on June 8 dragged on until four in the morning, fresh speakers summoned by telephone to testify into the night. Planning commission head James Felt would remember the meeting’s “

unreal and almost dreamlike quality.”

On the eve of a key primary election, Mayor Wagner asked the planning commission to withdraw its proposal, “so as not to leave an integral portion of Greenwich Village in a state of limbo.” But affirming its own independence, the commission ruled at its October 18 meeting that the neighborhood was indeed blighted and thus eligible for urban renewal. “The villagers, led by Mrs. Jane Jacobs,”

The New York Times

reported, “

leaped from their seats and rushed forward,” shouting that a deal had been made with a builder, that the mayor had been double-crossed, that the commission’s action was illegal. Chairman Felt pounded his gavel, demanding that order be restored, called in police. Shouted protests only increased. Felt called a recess, sent for more police, and, with the other commissioners, left the room. The West Villagers stayed where they were, chanting “Down with Felt!” When later chastised for their behavior Jane coolly replied, “

We were not violent. We were only vocal…We had been ladies and gentlemen and only got pushed around. So yesterday we protested loudly.”

Early the following year, responding to the neighborhood’s relentless pressure, Mayor Wagner finally prevailed on the planning commission to see things his way, which was Jane’s way; a newsletter of the Citizens’ Housing and Planning Council, a group supporting the commission, described the mayor as like “

a weary father asking his son to drop a young lady of dubious repute.” The neighborhood had won, as Jane would calculate, “

eleven months and ten days after our ordeal began.”

The victors, it is said, write the history books. But this time, the losers got their say, too. In his October 18 ruling, soon to be reversed by the mayor, Chairman Felt, troubled and resentful after what for him had been an ordeal, too, set out a long, measured, even philosophical defense of the commission’s action. The stance of the “

highly sophisticated and articulate opposition leadership,” he wrote, was rooted in “two premises,” with both of which he disagreed. First, that neither the planning commission nor public officials generally “mean what they say, can be believed, or can be trusted to do what they say they intend to do.” Second, that urban renewal and housing programs were inherently destructive, “and that only local residents, if left to their own efforts without the

interference of government,” can renew the city. This he called “the

laissez faire

theory of urban renewal.” He was right; this

was

, more or less, what Jane and her friends were saying. Today, for better and for worse—perhaps equally so—versions of both premises are deeply ingrained in American public life.

When it was all over, a friend from the United Housing Foundation, which had helped bring cooperative housing to poor areas of the city, wrote Felt a letter of sympathy and lament. It was fortunate, he wrote, that people like the West Villagers had never tried to block cooperative housing projects like those successfully brought to the Lower East Side: “They would have

discovered beauty in the colored drapes of the stores behind which the gypsies lived and in the old clothes shops that lined both sides of Grand Street from the East River to Third Avenue. The capacity of these people to find beauty in the cold water flats and the belly stove never ceases to amaze me.”

At a public lecture around this same time—she was back at

Forum

now and

Death and Life

was in print—Jane told of a rumor “that I had somehow

whipped up this book during the fight as a campaign document.” In a way, this was flattering. “I would love to be able to carry on a job, and a fight against the city, and whip up a book at the same time,” she said, but it was a long and lonely job to write a book, one that meant talking to herself interminably. Just now, she said, she was happy to be talking again with others besides herself.