Authors: Sergei Kostin

Farewell (42 page)

Then, a medical examiner, always the same one, certified the death. At the same time, the unit leader (number two) drew up the sentence execution certificate that had then to be signed by the prosecutor, the medical examiner, and himself. As the superiors were dealing with the paperwork, numbers five and six, usually the drivers of the vehicle used for the mission, wrapped the corpse in burlap. Then they carried the “package” away to a special section of a cemetery where it was buried with no distinguishing mark that would have helped find the grave.

Families of convicts who were executed, or died while in prison, were never allowed to recover the corpse or even find out which mass or anonymous grave held their loved one.

9

This is what happened in Vetrov’s case.

Svetlana and Vladik found themselves in a complete vacuum. No more phone calls, no more visits, as if the Vetrovs had never socialized with anybody. Only a few friends with no links to the KGB were there for them. Svetlana herself severed most of her relationships; she did not want to cause problems for the people she knew. Furthermore, she knew her phone was tapped. She did not care about being tailed in the street.

This affair, however, was not over for everybody.

“The Network”

Overnight, several people in Vetrov’s entourage found themselves closely watched by the KGB. A revealing fact is that the dragnet did not aim at Vetrov’s superiors nor at PGU internal counterintelligence officers who were in charge of preventing possible treason in their service. Saving the honor of their uniform once again, the PGU acted as if, having isolated the black sheep, its staff was beyond reproach. Any investigation was bound to expose serious negligence, to say the least.

Vetrov actually had the perfect profile of the average traitor. General Vadim Alexeevich Kirpichenko, who served twelve years as PGU first deputy head, must have been well-versed in Treason 101 since he formalized it in an article published in 1995.

1

He has passed away since then. Among other things, he supervised Directorate K (internal counterintelligence). Sergei Kostin had the opportunity to meet him in August 1996. This seventy-four-year-old man, unquestionably intelligent and stern looking, was still eager to learn. It was not possible to obtain much information from him about Vetrov, for whom he had only one word: “bandit.” According to the general, it was extremely difficult to spot a mole in one’s own ranks. In his article, he referred to the “recruitability model” articulated by the CIA, which on his own admission did not differ that much from the KGB’s. Intelligence officers likely to respond to rival services are characterized by “double loyalty” (loyalty in words only), narcissism, vanity, envy, ruthless ambition, a venal attitude, and an inclination to womanizing and drinking. Two categories of individuals deserve special attention. First, there are those who are not happy at work, thinking their professional accomplishments are not appreciated. Then, there are those going through a crisis, in particular in their family relationships, causing stress and psychological conflicts.

Summarizing the personality traits of promising recruitment targets, a CIA methodology document describes three types of potential traitors:

- The adventurer.

He aspires to a more important role than the one he has, and more in line with the abilities he attributes to himself; he wants to reach maximum success by any means. - The avenger.

He tries to respond to humiliations he believes he is subjected to, by punishing isolated individuals or society as a whole. - The hero-martyr.

He strives to untangle the complex web of his personal problems.

Vetrov combined all three types of traitor.

The general climate within the PGU was not conducive to showing attentiveness to others, helping a comrade, or simply being vigilant. The main concerns were getting a post abroad, climbing the hierarchical ladder, and being promoted. The competition was too fierce all around to afford the time to take an interest in guys who were finished, sidelined, and were no longer a threat as rivals.

The two men in charge of internal security within Soviet intelligence services provide a convincing case in point.

In the early eighties, department 5K was run by Vitaly Sergeyevich Yurchenko. This former submariner initially served in the KGB Third Chief Directorate (military counterintelligence and security). Transferred to the PGU Directorate K, he was nominated to the post of security officer at the Soviet embassy in Washington DC in the late seventies. Yurchenko had his moment of fame thanks to an unusual gesture, if not a suspicious one. He handed the FBI an envelope containing secret documents that had been thrown over the Soviet embassy’s wall by a former member of American secret services. The “walk-in” was arrested. To show its gratitude, the FBI sent a detective with a flower bouquet to bid farewell to Yurchenko when he left Washington in 1980.

2

Department 5K performances under Yurchenko in Yasenevo were modest. Investigations against officers suspected of being double agents were extremely rare, and none of them led to the unmasking of an agent guilty of sharing intelligence with a foreign power. This was attributed to the department’s lack of training and experience in counterintelligence, and also to the prevailing attitude rejecting the mere idea that an elite organization like the PGU could have traitors in its ranks.

3

There had to be another reason, and the future proved it with an event that was testimony to the decay within the Soviet intelligence services. Yurchenko, this guardian of officers’ loyalty and morality, defected!

4

Recently nominated to the post of PGU First Department deputy chief (field of operations: USA and Canada), he disappeared in Rome on August 1, 1985. Shortly thereafter, he emerged in Washington DC, where he underwent intense debriefing by the CIA. He is the one who, along with other information, gave American secret services the details about Farewell’s end and Howard’s treason. Strangely, three months later, he decided to go back to the USSR, and escaping the surveillance of two “guardian angels” from the FBI, he managed to reach the Soviet embassy. He told them a preposterous story. He had been kidnapped by the CIA in the Vatican, locked up in a secret villa, drugged with a psychoactive medication to make him talk, and so forth. Since his defection involved too many high-ranking KGB officials, this version was the one retained for public consumption. The KGB directorate behaved as if Yurchenko’s round trip to the United States was simply a PGU disinformation operation. Yurchenko was even awarded an Honored Chekist badge, presented by Vladimir Kryuchkov in a solemn ceremony, sickening all the intelligence officers present.

5

After having accepted these honors, Yurchenko disappeared. Some even think he was shot by firing squad. This is not the case. Sergei Kostin, with the help of his KGB contacts and through a next-door neighbor of Yurchenko’s in the countryside, was able to establish that Yurchenko was lying low. He refuses to meet journalists, whatever the subject matter.

Sergei Golubev, whom we met earlier, had a career path that, according to his superior, Oleg Kalugin, should have made him the perfect bait for any counterintelligence service in the world.

6

In the sixties, when he was operating under the cover of the Soviet consulate in Washington DC, he committed the same transgression as Vetrov did later in Paris. Driving his car while intoxicated, he hit a lamppost and was arrested by American police. He was not repatriated, though, and the incident had no adverse effect on his career. In 1966, he was nominated KGB resident in Cairo. Shortly before his transfer back to Moscow in 1972, he caused a drunken scandal in a public place. Again, what would have been fatal for the career of a mere mortal did not prevent Golubev from moving up the ladder. After his transfer back to Moscow from Cairo, he was appointed head of internal security for the PGU Second Service (counterintelligence). While at this post, Golubev was one of the linchpins in the assassination of Bulgarian dissident writer Georgi Markov in London in 1978, an event known as the infamous “poisoned umbrella” stabbing.

7

The permissive atmosphere prevailing in Yasenevo in those years and the grim aura that earned him his Great Inquisitor’s functions were no incentives for Golubev to reform. At the time Golubev was overseeing the Vetrov case, he was found one day, at five in the morning, dead drunk in his office, his desk strewn with dirty glasses, and his safe wide open. They claim he dropped to his knees, in tears, begging Kryuchkov for forgiveness.

Golubev survived, even after his former subordinate Yurchenko defected. Edward Howard’s defection to the Soviet Union in the mid-eighties amply compensated for the prolonged state of lethargy in the PGU security service. Directorate K took credit for the series of arrests in Russia after Howard revealed the names of Soviet CIA agents. This was the long-awaited hour of glory for the PGU counterintelligence service and his boss. Golubev was awarded the Order of Lenin, became a general, and was moved to deputy head of Directorate K. He retired and, like Yurchenko, declined to meet journalists until his death in 2007.

It is understood that if Vetrov’s treason had no adverse consequences at Directorate K, it caused even less of a stir at Directorate T. Only a few of Vetrov’s superiors were slightly reprimanded, including his department chief, Dementiev, and the head of Directorate T, Zaitsev. The most severe disciplinary action in the aftermath of the Vetrov case was the demotion of two employees for slacking off in controlling the use of the copy machine.

A few authors

8

mention a confession written by Vetrov shortly before his execution, which was a true indictment of his service. “I am adamant: there was no ‘last letter,’” protested Igor Prelin.

9

“I understand that the French and the Americans would like their agents to be their friends out of ideological beliefs, fighting the power of the Soviets. It would embellish their efforts. It’s one thing to recruit an agent through blackmail and corruption, but it’s another to win over a soul mate. There is nothing of the sort in Vetrov’s case.”

All the same, the existence of such a document seems plausible. It would be totally in line with his French handlers’ testimony regarding Vetrov’s hatred of the regime and of the KGB. Moreover, this confession, which told too many truths to be popular among the PGU readership, might very well have been buried in the safe of the Department 5K chief, Vitaly Yurchenko.

It would certainly have gone unheeded if Yurchenko had not decided to go for his short-lived defection to the West. An account of his testimony about this famous indictment was supposedly transmitted to the DST by the CIA as early as October 1985. The document appears to remain classified to this day. The DST, who would benefit from making the document public, denied us access to it and kindly invited us to come again, fifty years from now.

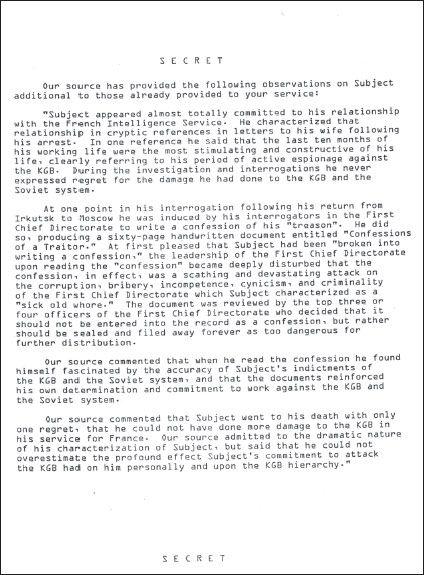

Certainly such a document would make Vetrov sound like a hero from an ancient classical tragedy, accusing his executors from a rostrum for all to be judged by history. The existence of this confession may sound too good to be true. Yet, after a few more weeks of research, repeatedly lodging requests with another fully credible source, we eventually found a copy of Yurchenko’s testimony; a few excerpts are reproduced here (

see Figure 9

).

Upon reading this CIA memo, it becomes clear why the KGB had all the reasons in the world to get rid of Vetrov’s confession.

It all began with one of Vetrov’s investigating magistrates asking him to write a letter in which he would express his regrets for having betrayed his country. By way of regrets, they received a last and exceptionally violent salvo. Although Vetrov’s last words are read here through the softening prism of a CIA memo, one can nevertheless sense his anger.

“[According to our source (Yurchenko)] Subject appeared almost totally committed to his relationship with the French Intelligence Service. […] During the investigation and interrogations he never expressed regret for the damage he had done to the KGB and the Soviet system. […] He was induced by his interrogators in the First Chief Directorate to write a confession of his ‘treason.’ He did so, producing a sixty-page handwritten document entitled ‘Confession of a Traitor.’ At first pleased that Subject had been ‘broken into writing a confession,’ the leadership of the First Chief Directorate upon reading the ‘confession’ became deeply disturbed that the confession, in effect, was a scathing and devastating attack on the corruption, bribery, incompetence, cynicism, and criminality of the First Chief Directorate which Subject characterized as a ‘sick old whore.’

Figure 9. CIA memo sent to the DST in October 1985. In his testimony, Yurchenko (former head of Soviet counterintelligence, who had temporarily defected to the West) gives a gripping account of the end of the Farewell affair, casting a vivid light on Vetrov’s last “Confession of a Traitor.”

“[…] Our source commented that when he read the confession he found himself fascinated by the accuracy of Subject’s indictments of the KGB and the Soviet system […].

“[…] Our source commented that Subject went to his death with only one regret, that he could not have done more damage to the KGB in his service for France. […]”

If, according to the investigation file, Vetrov never stopped prevaricating to reduce his sentence, this letter seems to bear the stamp of sincerity. With no hope left, he had nothing to lose. It is thus reasonable to consider his last cry for revenge as his legacy.

An exceptional event like treason in the ranks of the PGU required them to “bustle about” and “report about the progress made on the case.” Considering the extensive damage caused by Vetrov, it was concluded that he could not have possibly acted alone; there must have been a network.

And so, off went the KGB, launching a sweeping operation aimed at monitoring the main “suspects.” They were the Rogatins and a few individuals among their friends and relations. The campaign lasted over a year.