Fat Ollie's Book (3 page)

Authors: Ed McBain

“Then who?”

“I have no idea. My guess is he works here at the Hall.”

“Who would know?”

“You got me.”

“I thought you supplied everything. The sound, the lighting⦔

“The

onstage

lighting. Usually, when we do an auditorium like this one, they have their own lighting facilities and their own lighting technician or engineer, they're sometimes called, a lighting engineer.”

“Did you talk to this guy in the booth? This technician or engineer or whatever he was?”

“No, I did not.”

“Who talked to him?”

“Mr. Pierce was yelling up to himâHenderson's aideâand so was the councilman himself. I think the college kid was giving him instructions, too. From up in the balcony.”

“Was the kid up there when the shooting started?”

“I think so.”

“Well, didn't you look up there? You told me that's where the shots came from, didn't you look up there to see who was shooting?”

“Yes, but I was blinded by the spot. The spot had followed the councilman to the podium, and that was when he got shot, just as he reached the podium.”

“So the guy working the spot was still up there, is that right?”

“He would've had to be up there, yes, sir.”

“So let's find out who he was,” Ollie said.

A uniformed inspector with braid all over him was walking over. Ollie deemed it necessary to perhaps introduce himself.

“Detective Weeks, sir,” he said. “The Eight-Eight. First man up.”

“Like hell you are,” the inspector said, and walked off.

WHEN OLLIE GOT BACK

to his car, the rear window on the passenger side door was smashed and the door was standing wide open. The briefcase with

Report to the Commissioner

in it was gone. Ollie turned to the nearest uniform.

“You!” he said. “Are you a cop or a doorman?”

“Sir?”

“Somebody broke in my car here and stole my book,” Ollie said. “You see anything happen, or were you standin here pickin your nose?”

“Sir?” the uniform said.

“They hiring deaf policemen now?” Ollie said. “Excuse me. Hearing-

impaired

policemen?”

“My orders were to keep anybody unauthorized out of the Hall,” the uniform said. “A city councilman got killed in there, you know.”

“Gee, no kidding?” Ollie said. “My

book

got

stolen

out

here!

”

“I'm sorry, sir,” the uniform said. “But you can always go to the library and take out another one.”

“Give me your shield number and shut up,” Ollie said. “You let somebody vandalize a police vehicle and steal valuable property from it.”

“I was just following orders, sir.”

“Follow this a while,” Ollie said, and briefly grabbed his own crotch, shaking his jewels.

Â

DETECTIVE-LIEUTENANT ISADORE HIRSCH

was in charge of the Eight-Eight Detective Squad, and he happened to be Jewish. Ollie did not particularly like Jews, but he expected fair play from him, nonetheless. Then again, Ollie did not like black people, either, whom he called “Negroes” because he knew it got them hot under the collar. For that matter, he wasn't too keen on Irishmen or Italians, or Hispanics, or Latinos, or whatever the tango dancers were calling themselves these days. In fact, he hadn't liked Afghanis or Pakis or other Muslim types infiltrating the city, even

before

they started blowing things up, and he didn't much care for Chinks or Japs or other persons of Oriental persuasion. Ollie was in fact an equal opportunity bigot, but he did not consider himself prejudiced in any way. He merely thought of himself as discerning.

“Izzie,” he saidâwhich sounded very Jewish to him, the name Izzieâ“this is the first big one come my way in the past ten years. So upstairs is gonna take it away from me? It ain't fair, Izzie, is it?”

“Who says life has to be fair?” Hirsch said, sounding like a rabbi, Ollie thought.

Hirsch in fact resembled a rabbi more than he did a cop with more citations for bravery than any man deserved, one of them for facing down an ex-con bearing a grudge and a sawed-off shotgun. Dark-eyed and dark-jowled, going a bit bald, long of jaw and sad of mien, he wore a perpetually mournful expression that made him seem like he should have been davening, or whatever they called it, at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, or Haifa, or wherever it was.

“I was first man up,” Ollie said. “That used to mean something in this city. Don't it mean nothing anymore?”

“Times change,” Hirsch said like a rabbi.

“I want this case, Izzie.”

“It should be ours, you're right.”

“Damn right, it should be ours.”

“I'll make some calls. I'll see what I can do,” Hirsch said.

“You promise?”

“Trust me.”

Which usually meant “Go hide the silver.” But Ollie knew from experience that the Loot's word was as good as gold.

Like a penitent to his priest, or a small boy to his father, he said, “They also stole my book, Iz.”

Â

HE TOLD THIS

to his sister later that night.

“Isabelle,” he said, “they stole my book.”

As opposed to her “large” brother, as she thought of him, Isabelle Weeks was razor-thin. She had the same suspecting expression on her face, though, the same searching look in her piercing blue eyes. The other genetic trait they shared was an enormous appetite. But however much Isabelle ateâand right this minute she was doing a pretty good job of putting away the roast beef she'd prepared for their dinnerâher weight remained constant. On the other hand, anything Ollie ingested turned immediately toâ¦well, largeness. It wasn't fair.

“Who stole your book?” Isabelle said. “What book?” she said.

“I told you I was writing a novel⦔

“Oh yes.”

Dismissing it. Shoveling gravied mashed potatoes into her mouth. Boy, what a sister. Working on it since Christmas, she asks

What

book? Boy.

“Anyway, it was in the back seat of the car, and somebody spotted it, and smashed the window, and stole it.”

“Why would anyone want to steal your book?” she asked.

She made it sound as if she was saying “Why would anyone want to steal your

accordion?

” or something else worthless.

Ollie really did not wish to discuss his novel with a jackass like his sister. He had been working on it too long and too hard, and besides you could jinx a work of art if you discussed it with anyone not familiar with the nuances of literature. He had first titled the book

Bad Money,

which was a very good title in that the book was about a band of counterfeiters who are printing these hundred-dollar bills that are so superb you cannot tell them from the real thing. But there is a double-cross in the gang, and one of them runs off with six million four hundred thousand dollars' worth of the queer bills and stashes them in a basement in Diamondbackâwhich Ollie called Rubytown in his bookâand the story is all about how this very good detective not unlike Ollie himself recovers the missing loot and is promoted and decorated and all.

Ollie abandoned the title

Bad Money

when he realized the word “Bad” was asking for criticism from some smartass book reviewer. He tried the title

Good Money,

instead, which was what writers call litotes, a figure of speech that means you are using a word to mean the opposite of what you intend. But he figured not too many readers out thereâand maybe not too many editors, eitherâwould be familiar with writers' tricks, so he abandoned that one, too, but not the book itself.

At first, the book itself was giving him trouble. Not the same trouble he'd had learning the first three notes of “Night and Day,” which he'd finally got through, thanks to Miss Hobson, his beloved piano teacher. The trouble was he was trying to sound too much like all those pissant writers out there who were not cops but who were writing what they called “police procedurals,” and by doing this, by imitating them, actually, he was losing track of his own distinctiveness, his very Oliver Wendell Weekness, no pun intended.

And then he hit upon his brilliant idea.

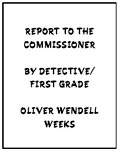

Suppose he wrote the book like a Detective Division report? In his own language, the way he'd type it on a DD form, though not in triplicate. (In retrospect, he wished he had written it in triplicate.) Suppose he made it sound like he was writing it for a superior officer, his Lieutenant, say, or the Chief of Detectives, orâwhy not?âeven the Commissioner! Write it in his own language, his own words, warts and all, this is me, folks, Detective/First Grade Oliver Wendell Weeks. Call the book “A Detective's Report” or “Report from a Detective” orâ

Wait a minute.

Hold it right there.

“Report to the Commissioner,” he said aloud.

He'd been eating when the inspiration came to him. He yanked a paper napkin out of the holder on the pizzeria table, took a pen from his pocket, outlined a rectangle on the napkinâ¦

â¦and then began lettering inside it:

And that was it.

He had found a title, he had found an approach, he was on his way.

“It was in the dispatch case you gave me,” Ollie said, “he prob'ly thought it was something else. Up the Eight-Eight, the only thing anybody carries in a dispatch case is hundred-dollar bills or cocaine. He prob'ly thought he was making a big score.”

“Well, hey,” Isabelle said, “your big

novel!

”

He would have to tell her sometime that skinny people shouldn't try sarcasm.

“Also they're tryin'a take away this big homicide I caught.”

“Maybe they'll show more respect once your big

novel

is published.”

“It's not that big,” Ollie said. “If you mean long.”

“Anyway, what's the big deal? Print another copy.”

“Do what?”

“Print another copy. Go to your computer and⦔

“What computer?”

“Well, what'd you do? Write it in longhand on a lined yellow pad⦔

“No, I⦔

“Write it in lipstick on toilet paper?” Isabelle asked, and laughed at her own witticism.

“No, I typed it on a

typewriter,

” Ollie said. “You know, Isabelle, somebody should tell you that sarcasm doesn't work when a person weighs thirty-seven pounds in her bare feet.”

“Only large persons should try sarcasm, you're right,” Isabelle said. “What's a typewriter?”

“You know damn well what a typewriter is.”

“Are you saying you don't have a

copy

of the book?”

“Only the last chapter. The last chapter is home.”

“What's it doing home?”

“I may need to polish it.”

“Polish it? What is it, the family silverware?”

“Nothing's finished till it's finished,” Ollie said.

“So as I understand this, everything but the last chapter of your book was stolen from your car this morning.”

“Five-sixths of my novel, yes.”

“What's it about?”

“About thirty-six pages.”

“Isn't that short for a novel?”

“Not if it's a good novel. Besides, less is more. That's an adage amongst us writers.”

“Didn't you writers ever hear of carbon paper?”

“That's why there are Kinko's,” Ollie said, “so you don't have to get your hands dirty. Besides, I didn't have time for carbon paper. And I didn't know some junkie hophead was going to break into my car and steal my book. It so happens I'm occupied with a little crime on the side, you know,” he said, gathering steam. “It so happens I'm a professional

law

enforcement officer⦔

“Gee, and here I thought you were Nora Roberts⦔

“Isabelle, sarcasm really⦔

“Or Mary Higgins Clark⦔

“I am Detective Oliver Wendell Weeks,” he said, rising from the table and hurling his napkin onto his plate. “And don't you ever forget it!”

“Sit down, have some dessert,” she said.

Â

DETECTIVE STEVE CARELLA

first heard about Fat Ollie Weeks being assigned to the Henderson homicide on Tuesday morning, when Lieutenant Byrnes called him into his corner office and tossed a copy of the city's morning tabloid on his desk.