Fatal North (24 page)

Authors: Bruce Henderson

Joe, “Eiberbing” (

NARRATIVE OF THE SECOND ARCTIC EXPEDITION COMMANDED Br CHARLES F. HALL

, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1879. From the collection of Chauncey Loomis.

)

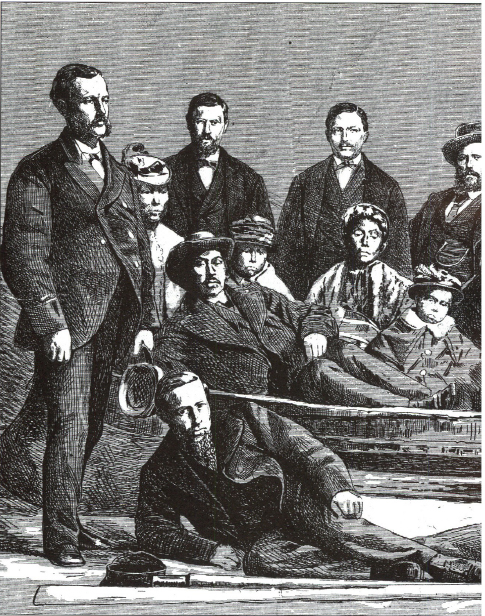

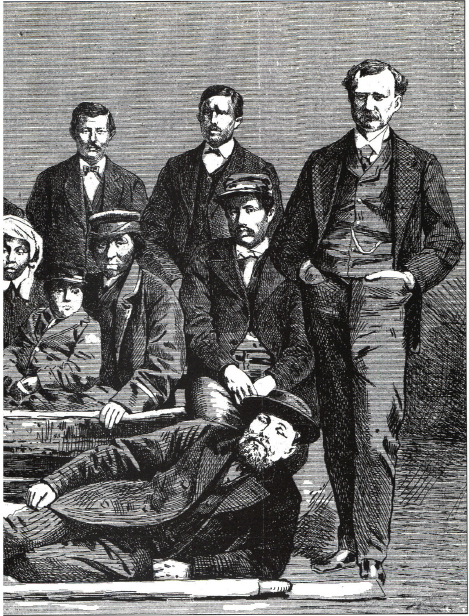

Captain Tyson and the Party Who Spent a Half Year on an Ice Floe

(from left to right)

Front row:

Peter Johnson, Frederick Anthing

In the boat:

The EskimosâHannah, Joe, Punny, Merkut Hendrik, Succi Hendrik, Augustina Hendrik, Tobias Hendrik, Hans Hendrik, and William Jackson, the cook (seated on the boat)

Standing:

Captain George Tyson, Gustavus Lindquist, William Nindemann, John Herron, John W.C. Kruger, Frederick Jamka, Sergeant Frederick Meyer (

The Tyson Collection, National Archives

)

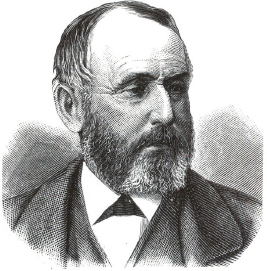

Sidney O. Buddington (

ARCTIC EXPERIENCES

, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1874

)

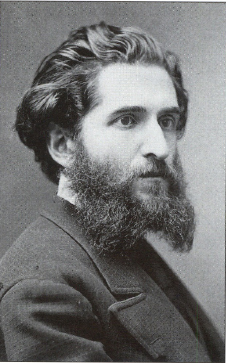

Dr. Emil Bessels (

Photograph by Julius Ulke. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

)

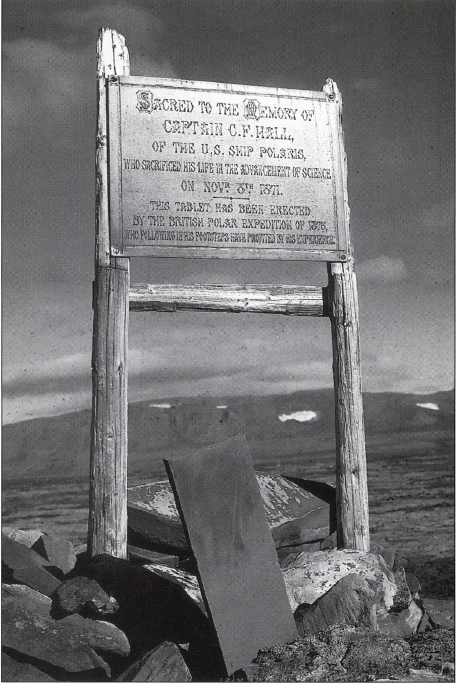

Grave site of Charles Francis Hall. (

Photograph by Chauncey Loomis

)

Charles Francis Hall in his grave, 1968. (

Photograph by Chauncey Loomis

)

15

Terror and Beauty

A

lone in the igloo he shared with Joe and Hannah, Tyson was startled when German seaman John Kruger barged in uninvited.

Wearing a long-barreled pistol at his side, Kruger angrily accused Tyson of “spreading lies” about his stealing food and committing other improprieties. The seaman berated Tyson in the most foul and hateful language, even threatening him with personal violence.

Tyson did not have far to be pushed. Fed up with the likes of this troublemaker, whom he had been ready to shoot a few days earlier for seizing Joe's seal catch, he coolly told Kruger that he was willing to let him try his “skill or luck” in any contest.

Tyson placed his hand on the butt of his loaded pistol.

Kruger, twenty-nine, seemed surprised by the overt challenge. He had apparently expected Tyson, older by more than a decade, to back down. When he left shortly thereafter, the seaman seemed to have shrunk a size or two. Perhaps, Tyson thought, he had been boasting to his cohorts about what he could do to the American officer and had been dared by them to act imprudently.

I know not how this business will end; but unless there is some change, I fear in a disastrous manner,

Tyson wrote in his journal.

They are like so many willful childrenâall wanting to do as they please, and none of them knowing what to do.

The next day, Tyson received word that the Germans had decided against trying for Greenland, at least for the time being. He found himself thinking the decision had less to do with their collective wisdom than the fact that they had been housed all winter, safely out of the worst elements and not having to fend for themselves. While in their igloo the men might talk bravely about their plans, but let them get out in the cold for a short time and all their pluck was frozen out of them.

For two days in a row Joe brought home game, a small seal on January 23 and a considerably larger one the next day. He had been obligated to go about six miles, hopping dangerously from one floe to another, until finding seal. Joe had staked out blow holes, and the moment a seal put up his snout to breathe, he was quickly speared.

Both seals were taken into Joe's hut to be cleaned and divided. The men had learned that skinning a seal was not pleasant work, and they were now willing to have it done for them. As a precaution against accusations of unfairness, Tyson invited two of the men to watch, but they declined. He instructed that half the meat, blubber, and skin go to the men's igloo, and the other half was divided amongst the two Eskimos huts.

The larger seal in particular furnished a fine meal for all. Tyson hoped that with full stomachs, everyone would find themselves in an improved frame of mind. As for himself, he dined on a small piece of raw liver, warmed seal meat, and pemmican tea with a little fresh seal blood. He now wholeheartedly agreed with the Eskimos about the recuperative benefits of seal blood.

Hannah prepared “tea” by pounding a slice of bread very fine, then for flavor melting a few chunks of saltwater ice in a tin can over the lamp. She then mixed in the pounded bread and

pemmican, and warmed up the mixture. It reminded Tyson of greasy dishwater, but when a man was near starvation, he could ingest many things that his stomach would otherwise find revolting.

The offal of better days is not despised by us now.

For dessert he had sliced blubber seared over the lamp.

As they dined, they were permeated with dirt not seen at a civilized table. They could scarcely get enough water melted to serve for drink, and could spare no hot water for bathing. The “carpet” spread out over their floor of ice was a bit of old canvas. When Hannah had taken it into the sunshine to pound out for the first time, it was a sight to behold: clinging black icicles hanging on a cloth encrusted with the accumulated drippings of grease, blood, saliva, ice, and their dirt for four wearying months, not all of which could be removed with their limited means of cleaning. Tyson was glad the interior of the hut was not well lit, for some things were best left unseen.

Settling back for a smoke of his pipeâhe still had a little tobacco left for that daily comfortâhe kicked his heels together, trying to get some warmth back in his feet. Finally, as satisfied as one could be trapped on an Arctic ice floe in subzero temperatures, he slipped beneath thick musk-oxen skins and turned in for the night. He awakened in the morningâtheir one hundred and third on the iceâto the coldest temperature they had yet experienced on the floe: minus 42 degrees.

As a ship's captain, Tyson had relieved parties stranded on ice. They had not drifted so long, to be sure, nor come so far, nor had there been so many of them, and they were always men, not women and children. But they had been far away from their ships, hungry and destitute. He had rescued some runaways from the

Ansel Gibbs,

and another party separated by accident from the brig

Alert.

He had also relieved Captain Hall twice on his earlier land expeditions, at times when Hall was most pleased to see a relief ship.

Tyson prayed that Providence might send his party a rescue before it was too late.

* * *

The hunters each took a dog in the hope of tracking a bear. Hans lost his dog when he removed its harness and they became separated from each other in a gale; the dog was never seen again. Joe returned with “Bear” loyally at his side, but upon their arrival, the large dog lay down, closed his eyes, took a few shallow breaths, and died.

Without a surviving dog, it would be a difficult matter to hold a bear at bay for a hunter to get off a shot. The dogs would be missed, too, for their usefulness in pulling loads over the ice.

The loss of the party's last and favorite dog was a sad event. Tyson had fed Bear the night before, sharing what he was eating: seal skin and some well-picked bones. It may, he thought, have been the bones that caused the dog's death, as Bear had hungrily swallowed large pieces.

Bear's passing was the first and only natural deathâanimal or humanâto occur on the ice floe in three months; surely a wonder considering the conditions they all had endured. Tyson wondered if hope played a role in survival. Hope could help keep humans alive but not a poor beast like Bear. The Newfoundland had felt all their present miseries, no doubt, but could not anticipate relief. Had Bear given up? Had he died from lack of hope?

Even now, with a new storm raging without, and while fierce hunger raged within, and though sometimes overcome with great sadness and despair, Tyson could think of family, children, and friends at home; he was not without hope.

Feb. 1. God, in creating man, gave him hope. What a blessing! Without that we should long since have ceased to make any effort to sustain life. If our life was to be always like these last months, it would not be worth struggling for; but I seem to have a premonition, though it looks dark just now, that we shall weather it yet. Hope whispers, “You will see your home again. The life-spark is not going to be extinguished yet. You shall yet tell the story of God's deliverance, and of this long trial.”