Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine (12 page)

Read Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine Online

Authors: Julie Summers

Tags: #Mountains, #Mount (China and Nepal), #Description and Travel, #Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Andrew, #Mountaineering, #Mountaineers, #Great Britain, #Ecosystems & Habitats, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Irvine, #Everest

Odell left London on Maundy Thursday afternoon. Sandy had already arrived by train from Oxford and was installed at Highfield when he and his wife Mona arrived. After a good dinner and an excellent breakfast the following morning, the Odells, Geoffrey Summers and the two Irvine brothers left for Capel Curig. Then, as now, Capel Curig was the major destination of all climbers in North Wales. From there the Snowdon range is easily accessible, as is the Carneddau range and, slightly further afield, the splendid rocks of Cader Idris, which boasts some of the most spectacular mountain scenery in the area.

Odell was a meticulous diarist and kept careful jottings of each key place they passed, every familiar view he saw and everybody he met. They drove, via Ruthin, passing by the great shadowy hulk of Moel Famau and down into the Vale of Clwyd and across the Denbigh moors to Betws y Coed and then on to the Royal Hotel in Capel Curig where they were to be based for the weekend. They were a very congenial and cheerful party when they met up in Capel with Woodall, an old friend of Odell’s, who was also spending his Easter climbing. It was a fair bet that Odell would meet several acquaintances and friends over the course of the weekend, so small was the climbing world at the time, but Sandy was nevertheless very impressed by the fact that people recognised him. That afternoon they made a brief excursion to clamber on some rocks near Capel and came back to the Royal for dinner.

The following morning they set off in glorious sunshine to climb the Great Gully on Craig yr Ysfa. The Great Gully was described by the Abrahams in their pre-First World War book on the rock climbs of North Wales, as a ‘lengthy expedition of exceptional severity’. This was a far more technical climb than either Sandy or Hugh had ever done before, so Odell led and gave instruction. He noted in his diary: ‘found great chimney v. wet & difficult, & after 2 failures to get above chockstone, Sandy got up it with great difficulty a fine effort for 1

st

lead! I led remainder to top of climb: we all got v. wet in gully; took about 5 hrs, but v. fine climb.’ Odell was clearly very impressed by Sandy’s ability to overcome the difficulties of the gully, referring to it in his obituary notice in the 1924

Alpine Journal

as ‘a brilliant lead for a novice’.

The following day the weather was not as beautiful as it had been on the Saturday, but the team, this time including Mona, was not daunted. They drove via Beddgelert, past the Pen-y-Gwryd hotel in Snowdonia, a hotel frequented by mountaineers both then and now, where the Odells had spent their honeymoon. The hotel’s bars are full of climbing memorabilia and photographs of famous climbers who have stayed there. When I visited it with my father we were delighted to see a photograph of Sandy at Everest Base Camp in the bar.

The party had planned to walk and climb in the Cader Idris group which they approached from Dolgellau, a road that meanders along the shore of Llyn Trawsfynydd. They left the car on the road and went up the track to Llyn y Gadair from where they climbed a very difficult buttress called the Cyfrwy Arête, a superb climb and always thrilling. It took about four hours to climb to the top where they had lunch looking down an almost vertical drop onto Llyn Cau. There, according to Odell’s diary, it hailed on them. On the summit of Pen y Gadair (2927 ft) the weather picked up and they were afforded magnificent views as they descended via Fox’s path to the west of the lake Llyn y Gadair and back to the car. The whole excursion took a good twelve hours and they didn’t get back to Capel until midnight.

On Easter Monday they drove to Pen y Pas which, in the pre-First World War years had played host to Geoffrey Winthrop-Young’s climbing parties in which George Mallory had frequently been included. From there they climbed Route II at Lliwedd in the Snowdon massif where they met Winthrop-Young, David Pye and two other well-known Alpine Club members, Shott and Bicknell.

On Tuesday on their return from the hills they found a large Summers party at Capel who had arrived for dinner. Doris, Marjory and Dick Summers, who was presumably buttonholed to drive the ladies from Flint, left Capel Curig with Sandy after the meal and motored back to Highfield. Odell and Mona stayed on and left the following morning after breakfast, catching the train from Chester. Sandy had passed the test as far as Odell was concerned and moreover had impressed him with his strength, determination and agility.

Odell very quickly became a role model for Sandy. He had the knack of making people feel comfortable and Sandy responded to his gentle but perceptive humour. He was always happy to share his vast experience and as a superb raconteur he found a very willing and avid listener in his young protégé. What strycj Sandy about Odell more than his climbing record and the contacts he had in the mountaineering world, two of whom – George Abraham and Arnold Lunn – he was subsequently to meet and who played a major role in his life, was Odell’s ambition. Not only was he about to embark on a second Spitsbergen expedition but he was also on the short list as a member of the climbing party for the 1924 Mount Everest expedition and this could not have failed to register with Sandy.

In the spring of 1923 Willie had taken a lease on Ffordd Ddwr Cottage, Llandyrnog which the family used as a weekend retreat. Sandy couldn’t pronounce the Welsh spelling of the name so immediately christened it ‘fourth door’, a name which stuck for the two years the family had the house. How this tiny half timbered seventeenth century cottage accommodated the family and the children’s university friends remained a mystery until I came across a photograph of the cottage with two bell tents standing in the field immediately in front of the house. The family regularly attended Sunday worship at St Tyrnog’s church and I discovered that the rector, the Reverend William T. Williams, was not only another Willie, but quite a figure in the locality. He was known as Pink Willie by virtue of his prominent red nose and was a keen supporter of the Irvine family, congratulating Sandy in the summer 1923 parish magazine on his rowing Blue and Evelyn on her hockey Blue. Sandy was staying in Ffordd Ddwr before he left for Spitsbergen and his adventures on that expedition, as well as on the Everest one were closely followed by the locals. They took quite as much pride in their ‘son’ as others.

It was at about this time that Marjory really set her sights on Sandy. She had known him as a regular and entertaining visitor to Cornist as a friend of Dick’s since early in her marriage to HS. A natural flirt and one who adored the limelight, she had begun to find Sandy increasingly interesting. In addition to his striking good looks and charming manner there had been added the heroic win over Cambridge in the Boat Race with all its attendant publicity. It was, for Marjory, an intoxicating mix and one she was unable to resist. Sandy was surprised, delighted and flattered by her attentions and over the spring and summer of 1923 the flirtation blossomed into a non too discreet love affair. She loved to be seen with him and, to Dick and Evelyn’s horror, turned up all over the place in his company. There was nothing they could do or say, Majory was her own woman and Sandy did not take kindly to interference in his private affairs; in fact it was something which he never tolerated and both Dick and Evelyn knew better than to comment. Marjory went to Henley where she conspicuously joined him and his Merton friends; she took him out to the theatre in London, she joined in picnics and walks in Wales not caring what anyone thought of her and was a frequent visitor to Highfield, Geoffrey Summers’s home, for Sunday lunch with Sandy. She seemed unconcerned for HS’s feelings, and indeed for those of his children and pursued Sandy with abandon.

Sandy and Marjory at Cornist Hall, April 1923

Sandy and Marjory at Cornist Hall, April 1923

Preparations for the Spitsbergen expedition took up a good deal of Sandy’s time during the summer of 1923. In a frequent exchange of letters he received instructions from Odell about equipment and clothing. Sandy’s aneroid barometer and compass were the subject of much of the correspondence. The barometer required calibration and the compass had to be filled with 60 per cent absolute alcohol since the usual 40 per cent would freeze in the Arctic. Odell, utilizing Sandy’s organising skills, put him in charge of getting Milling properly kitted out with Shackleton boots, crampons and skis and reminded him that the boat was leaving two days earlier than originally planned.

Odell himself was busy with his own preparations and also with testing the proposed oxygen apparatus that the 1924 Everest expedition would be taking with them the following spring. He had been appointed oxygen officer for the expedition by the oxygen subcommittee and June 1923 found him climbing with Percy Unna on Crib Goch in North Wales testing the kit.

George Binney was hoping that his expedition would be able to carry out survey work in the hitherto unexplored regions of the ice-capped island of North Eastland. The only maps in existence dated from the eighteenth century and were known to be inaccurate. In his expedition prospectus, a closely typed sheet of foolscap, he stated the aims of the expedition:

George Binney was hoping that his expedition would be able to carry out survey work in the hitherto unexplored regions of the ice-capped island of North Eastland. The only maps in existence dated from the eighteenth century and were known to be inaccurate. In his expedition prospectus, a closely typed sheet of foolscap, he stated the aims of the expedition:

Exploration

(if Ice conditions are favourable) of the many islands of the Franz Joseph Land or East Spitsbergen Archipelago or the coastline of North East Land.

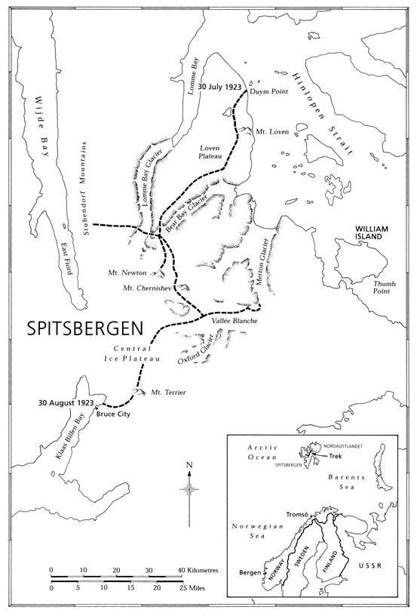

It is further hoped to continue the work of the exploring party of the 1921 Oxford University Spitsbergen Expedition. They attempted to traverse from West to East Spitsbergen but were unable to complete it. It would be possible, working from the East Coast, to complete this important piece of work. Any observations the expedition can make on the coastline of North Eastland will be of importance, as practically nothing is known of portions of this coast.

Full data of the ice conditions and of the temperatures and such errors as are discovered in the charts (which are by no means perfect) will be recorded and placed at the disposal of the Admiralty on the return of the expedition.

Details of the natural history, glaciology and geology follow with the last paragraph alluding to the hunting and shooting of polar bear, walrus, whale, seal and reindeer.

‘The expedition will first attempt to reach Franz Joseph Land. If headed off by the ice pack, we will make for the East Coast of Spitsbergen, and, given favourable conditions, attempt the circumnavigation of North Eastland (from East to West) and reach East Spitsbergen from the North through the Hinlopen Straits.’

The plan relied heavily on the weather and the state of the ice pack being in their favour but Binney’s experience in 1921 had lead him to caution: ‘I have stated the possibility of the expedition work, but decisions can only be made on the spot. It is useless to formulate an accurate plan beforehand.’ It was an ambitious venture for a small expedition team with only a month at their disposal.

Each member of the expedition had to pay a sum towards the cost of their second class travel, the share in the charter of the ship and ‘adequate food throughout the expedition’ although alcoholic drinks were not included.

There was much interest in the expedition, particularly from the press, and Binney was called upon for interviews and, from the expedition itself, dispatches. Before leaving he told a journalist: ‘The expedition is fully equipped for scientific work in the fields of survey, ornithology, geology, and the study of glacial conditions, and a collection will also be made of flora and fauna.’ He added, ‘It will be necessary to depend to some extent on “shooting for the pot”, and it is hoped that reindeer and polar bears may be found as well as seal and walrus. In fact, the expedition has undertaken, if possible, to capture a walrus for the Zoological Gardens.’ They could not rely, however, on the pot shot, and the sledging party, especially, had to cater for extreme conditions when they might be prevented from reaching the ship and therefore having to survive for a longer period on their rations. As they sailed from Newcastle on the SS

Leda

they had with them four and a half tons of provisions, enough food for one year, in part organized by Willie Irvine, who was acting as agent to the expedition. The press was particularly interested in the consignment of bull’s eyes (peppermint sweets) which ‘have a real value in the Arctic, as they are nutritive and stimulating in cold weather’.