Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine (29 page)

Read Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine Online

Authors: Julie Summers

Tags: #Mountains, #Mount (China and Nepal), #Description and Travel, #Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Andrew, #Mountaineering, #Mountaineers, #Great Britain, #Ecosystems & Habitats, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Irvine, #Everest

The route through the forest from Pedong ‘was very delightful through sunlit glades over roads of stone full of mica which looked like silver in the sun’. From Rangli the road began to rise and the bathing stopped, much to Sandy’s regret. The route led up towards the first of the high passes the expedition would encounter and it was on this road through the forest that Sandy had his second incident with his pony. He was in the process of trying to overtake a mule loaded with cotton when it was nipped in the bottom by another mule from behind. The loaded mule did not take kindly to this aggressive nibble and leapt forward, dislodging a bale of cotton which knocked into Sandy’s pony and sent them both tumbling down the hill from the narrow rocky path. Fortunately there was a ledge some ten feet below which broke the fall and the pony scrambled at the edge just long enough for him to jump clear before they both rolled down the hillside together. ‘Fortunately the beast came off with only a slightly cut hock & I got away with a scraped knee.’ In a similar incident some days later Odell did not come off so well and had his knee badly crushed in a fall from his pony. Riding seems to have been altogether one of the main hazards of the trip.

Another, unseen hazard was the stream water. They had been given a long lecture before they left Darjeeling on the dangers of drinking from the streams and rivers. One of the recurring themes of the previous two expeditions had been the debilitating gastric problems that had afflicted several members and which had contributed to the death of Kellas in 1921. General Bruce, mindful that he needed the very fittest and strongest team of climbers available when it came to making the assault on the mountain, asked Hingston to make every effort to keep the men as healthy as possible. Thus, when confronted with thirst and a fresh stream, they all felt a great deal of guilt as they broke the pledge and drank from the waters.

As the route rose out of the valleys they reached their first pass, above Sedongchen. At 5500 feet it was the same height as the peak Sandy climbed in Spitsbergen with Odell the previous summer. They stopped at the little tea house at the top of the pass and agreed that this march was the most beautiful one they had done up to now. The forests were of rhododendron all mauves, pinks, cerise, cream and white with butterflies and birds darting in and out above their heads. The march passed through several villages with their mud-lined huts and rush roofs. Sandy thought the people to be very cheery and friendly, much more so than the folk in the Indian villages closer to Darjeeling. He couldn’t resist a familiar comparison: ‘some of the women look just like Aunt T.D. in spite of the rings in their noses’ and the very pretty girls pleased him greatly as they knew ‘how to turn themselves out to the best advantage’. As if to reassure his mother that it was not only the girls who fascinated him, he went on to describe in some detail his feelings about the religion, which he found very romantic. ‘Most of the houses have tall bamboo poles with a strip of flay all the way down with prayers written all the way down in their strange hieroglyphics. The idea is that the wind wafts the prayers off to their gods … I think it’s a shame that missionaries come and put strange and far less romantic ideas into their heads.’ Naïve and innocent as this remark might seem, I don’t think it would have gone down particularly well at Park Road South, where several Irvine relatives had worked as missionaries in India. With the knowledge that he was several thousand miles away from home he probably felt comfortable at making a gentle dig at his family’s devout religious beliefs. This theme recurs again, later in the trek, when he gets to Shekar Dzong.

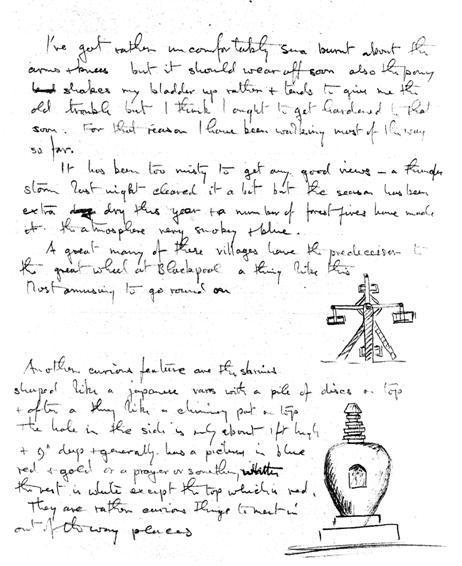

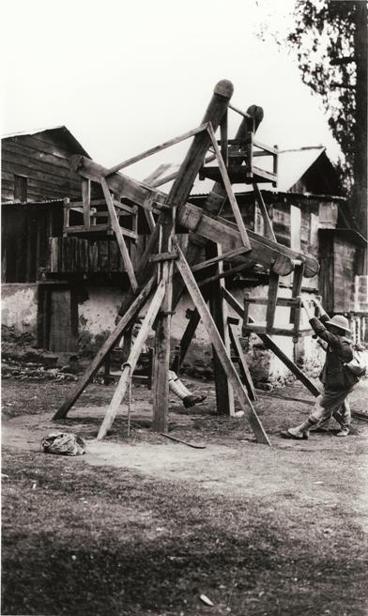

Several of the villages had a form of merry-go-round which Sandy described as ‘the predecessor to the great wheel in Blackpool’ and on which he and Mallory were photographed by Odell. He made a sketch of it in a letter as it had clearly caught his eye, as had the Tibetan shrines which he also drew for his mother. ‘They are rather curious things to meet in out of the way places.’

Letter from Sandy to Lilian

Letter from Sandy to Lilian

Sandy pulling Mallory on ‘the predecessor to the great wheel in Blackpool’ photographed by Odell

Sandy pulling Mallory on ‘the predecessor to the great wheel in Blackpool’ photographed by Odell

From the very beginning of the march Sandy’s fair skin caused him great problems. He burned his elbows and knees badly in Sikkim but it was his face that was to cause him the greatest agony later on. By mid-April he had serious sunburn to his face and had lost several layers of skin around his nose and mouth. Most of the other members grew beards to protect their faces, but Sandy, for some reason, elected to keep himself free from facial hair. He was also painstaking about his daily washing and this did not go unremarked by the other members of the party. Norton, in a dispatch to the Times, went into some detail about the habits of the expedition members. ‘The effect of the sun and wind is less felt than previously, thanks to the early issue of lanoline and vaseline, and to the cautious avoidance of the ultra-English vice of cold bathing in the open. Thus we have retained a high average proportion of skin on the nose, lips and finger-tips. … In this respect a fair man offers the most vulnerable target, and the Mess Secretary seems to have hit on the expedient of growing a new face every second day, but then he is suspected of indulging in the said English vice, or why his frequent pilgrimages in the direction of a frozen stream, clad principally in a towel?’

The trek followed the route from Guatong to Langram where they encountered snow for the first time. ‘It was very curious’, Sandy wrote, ‘to change from almost tropical climate to above the snow line in 3 hours.’ The going was much rougher here than it had been up until now and several of the ponies slipped and fell. When they arrived in Langram Sandy settled down to another afternoon with the oxygen apparatus. More trouble. He found that all but one of the oxygen frames had been more or less damaged in transit and worked away well into the night repairing them with copper rivets and wire.

As the route gained height so the affects of altitude were beginning to be felt. On 1 April they crossed the Jelap La, at 14,500 feet, from Sikkim into Tibet. Sandy climbed 3000 feet in one morning and noted that he ‘felt a slight headache towards the top, especially if my feet slipped & shook my head much. I felt quite tired in my knees & panted a good deal if I tried to go fast. At the top of the pass put the largest stone I could lift on the cairn from about 20 yards away, just to make sure that the altitude wasn’t affecting me unduly! Anyway I was quite glad to sit down for a few minutes, the altitude being my record up to date, 14,500 ft.’ He took photographs of the cairn with its prayer flags fluttering in the wind and continued down from the pass into Tibet on foot. He was interested in the different characteristics of this side of the pass, where the tree line was some 2500 feet higher than on the other side. They had come from a valley of lush vegetation into a dryer and cooler valley in the lee of the pass where the trees were now predominantly pine.

Norton was very pleased to record in his diary that he had felt absolutely no effects at all from the same altitude, observing that his performance to this height was considerably better than it had been in 1922. This concurs exactly with Hingston’s later findings, that the climbers who had already been to altitude on previous occasions acclimatized far more quickly than those who had not. Whenever Sandy reached a new altitude record he was blighted with a headache. Odell, too, was suffering somewhat from the altitude, but he was also affected with a gastric complaint: ‘mountain trots, I expect’, Sandy noted somewhat disingenuously in his diary. A fall with his pony only added to his woes. It fell and landed heavily, crushing Odell’s knee and leaving him stiff and sore for a few days. Mallory, however, was full of energy and bounding ahead of the others on the march. When Sandy was not keeping up with Mallory he walked with Shebbeare. The two of them seemed to have a good understanding and Sandy described him as ‘a very fine specimen of a man & most awfully wise. He impresses me more every day.’

They spent the night of 1 April in a ‘no good’ guest house where the first party had stayed the previous night and Geoffrey Bruce had left them a half bottle of whisky with a note saying that they had plenty with them. They were all delighted by the find and, with the prospect of five teetotal months ahead of them, spent quite some time discussing the best way to make the most of this unexpected gift. In the end they decided to take it in their tea and they all declared they’d loved it until Shebbeare tried a drop neat and discovered it was the dregs of the whisky bottle filled up with tea. It was only then that they recalled the date. ‘We’ll have to hush this up from the first party!’ Sandy wrote. Being only a few days into their march and still full of the beer and the benevolence of civilization, they thought it quite a good April Fool’s joke. ‘I doubt is we should have thought it funny a few weeks later when we were beginning to feel the strain.’ Shebbeare wrote, ‘There were times later on when we ran short of sweet things (we were never short of food) when an irregularly broken stick of chocolate seemed a premeditated plot to defraud us of our share.’

The Chumbi valley, which leads down from the Jelap La, has a very different climate from that of the Sikkim side. Now they were walking in warm rather than hot sunshine and the whole area was dryer and the going on the roads much rougher. They arrived in Yatung where they joined the first party and were entertained by the son of the British trade agent, John MacDonald, who instructed them in Tibetan etiquette and table manners. ‘The chief difference between Tibetan and English table manners (besides the use of chopsticks) is that the more noise you can make in dealing with such things as vermicelli soup the better from the Tibetan point of view,’ Shebbeare recalled. Fully briefed the party was given seats of honour and treated to a performance of Tibetan Devil Dancers. This weird and wonderful performance lasted for four and a half hours during which time they were plied with rakshi and chang by two very attractive girls, one Tibetan, one Chinese. Rakshi is distilled barley which the Tibetans claim to be 100 per cent proof, while chang is their local beer which Sandy described as looking like ‘very unfiltered barley water’. Tibetan hospitality brooks no refusal so the wise men among the party, including Shebbeare, kept strictly to the Chang and remained almost sober. Others, less experienced, were somewhat worse for wear the following morning. The dancing was extraordinary and they were all fascinated by the performance. Shebbeare described it most evocatively: ‘The best of the performers seemed to be leaning inwards at quite 45°, spinning on their own axes as well as working round the ring and looking, in their long dokos, like milk churns being trundled along a platform.’ Towards the evening Sandy ran back to his tent to put a colour film in his camera and photographed the dancers in the evening light. They were all in very good spirits by the time they left the performance and had to negotiate a single tree bridge above the foaming river Amo-Chu in order to get back to their camp. Some of the porters were in a bad state and had to be helped across the bridge. Fortunately no one ended up in the river.

The next morning one of the girls who had been serving drinks came over to the camp selling blankets and coloured garters. Sandy, clearly quite taken by her, bought three pairs of garters and took a colour photograph of her. That day the first party left with Norton, while the general, who was not feeling well, remained with the second party in Yatung. Sandy spent the day wrestling with the badly smashed-up oxygen carriers and taking a short walk with Mallory where they hoped to find some rocks to climb on. The cliffs were full of grass and gave no good holds so they had to give up and return to camp. That night two muleteers got very drunk and bit a Tibetan woman. Bruce fined the men and their punishment was to carry the treasury, which weighed 80 pounds, as far as Phari, a three-day march. In order to ensure that none of the porters was carrying a load lighter than 40 pounds the expedition had a set of brass scales where the loads would be checked regularly. Bruce was fair but tough with the men and this punishment meant they had to carry twice the normal weight.