Feminism (13 page)

Authors: Margaret Walters

Tags: #Social Science, #Feminism & Feminist Theory, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #History, #Social History, #Political Science, #Human Rights

The situation changed forever as a result of the First World War. In August 1914 Emmeline Pankhurst sensibly announced that the campaign for the vote was suspended. Christabel – whose sojourn in France seemed to have atrophied her ability to think clearly –

remarked melodramatically that ‘a man-made civilisation, hideous and cruel in time of peace, is to be destroyed’. The war, she continued, was ‘God’s vengeance upon the people who held women in subjection’. Sylvia, always far more thoughtful, remarked in

The

Suffragette Movement

that

Fightin

men and woman had been drawn closer together by the suffering and sacrifice of the war. Awed and humbled by the great

g for th

catastrophe, and by the huge economic problems it had thrown into

e v

naked prominence, the women of the suffrage movement had learnt

ot

that social regeneration is a long and mighty work.

e: su

ffr

a

In 1918, women over the age of 30 were given the vote; and in

gett

March 1928, under a Conservative government, they finally won it

es

on equal terms with men.

85

During the early 20th century, English women achieved legal and civil equality, in theory if not always in practice. Some women, those over the age of 30, were allowed to vote from 1918, and there were arguments about whether their priority was to press hard for enfranchisement on the same terms as men, or to concentrate on women’s other needs and problems. Some women, and some men, felt that a woman’s party might have helped them build on the gains they had already achieved, but the opportunity was let slip.

The effects of the First World War had been so complex that it is impossible to generalize about them. It had allowed some women the opportunity to work outside the home; in the war years, the number of women employed outside the home rose by well over a million. Some worked in munitions factories and engineering works, others were employed in hospitals; many demanded pay rises, sometimes insisting their wages should be equal to men’s. A Women’s Volunteer Reserve was formed, and there were some Women’s Police Patrols. Their contribution during the war, both domestically and as workers outside the home, almost certainly contributed to their partial enfranchisement in 1918. But many women were left widowed or unmarried, and the war-time press had talked darkly about ‘flaunting flappers’. Sylvia Pankhurst commented, sarcastically, that ‘alarmist morality-mongers conceived most monstrous visions of girls and women . . . plunging 86

into excesses and burdening the country with swarms of illegitimate children’. One feminist paper remarked that military authorities did not realize that ‘in protecting the troops from the women, they have failed to protect the women from the troops’.

As early as 1918, MPs agreed that women could actually sit in parliament, though it was only slowly that women were actually elected. Christabel Pankhurst stood for Smethwick in 1918, but lost by 700 votes. In 1919 and 1920, two women – the Conservative Lady Astor and the Liberal Margaret Wintringham – succeeded to their husbands’ seats. Astor had never been particularly involved in the long struggle for the suffrage, but Wintringham had been a member of the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC), and also of the Women’s Institute. She went on to proclaim, publicly, that homemaking was a ‘privileged, skilled and nationally

Early 20th-centur

important occupation’.

The Labour Party member Ellen Wilkinson – an unmarried woman with a trade union background – was elected in 1924, and she was

y feminism

impressively outspoken on a whole range of issues; she was keenly interested in women’s domestic role and argued for family allowances; she supported trade union rights; and she was a member of an International League for Peace and Freedom delegation that investigated reports of cruelty by British soldiers in Ireland. ‘The men come in the middle of the night and the women are driven from their beds without any clothing other than a coat’, she wrote: ‘They are run out in the middle of the night and the home is burned.’

In 1929, Lady Astor suggested that women MPs form a women’s party, but the notion fizzled out when Labour women were reluctant to support the idea. (Some modern historians have argued that this was a real opportunity that was thrown away.) As late as 1940, when a coalition government was formed, there were only 12

women MPs. Local government seemed a more favourable area for politically concerned women. Ever since the 1870s, women had 87

been actively serving on school boards and other local bodies, and their numbers increased after the war.

NUSEC’s broader aim had been to ‘obtain all other reforms, economic, legislative and social as are necessary to secure a real equality of liberties, status and opportunities between men and women’. Its members campaigned, for example, to open the professions to women, and argued their right to equal pay. In 1919, the Sex Discrimination (Removal) Act, in theory at least, opened the professions and the civil service to women. According to Virginia Woolf, the Act did more for women than the franchise, but modern historians have expressed doubts, at least about its short-term efficacy. In 1923, a Matrimonial Causes Act established equal grounds for divorce between men and women.

But NUSEC was concerned, not simply with equality, but with

difference

; its members tried to tackle women’s special problems and needs. When Eleanor Rathbone became president, she argued

minism

that women should demand, not equality with men, but ‘what

Fe

women need to fulfil the potentialities of their own natures and to adjust themselves to the circumstances of their own lives’. Their demands included reform of the laws governing divorce, the guardianship of children, and prostitution. In 1921, the Six Point Group was founded; it included some former militants, including the journalist and novelist Rebecca West, but its demands, and methods, were hardly radical. They too addressed women’s special problems, arguing for a better deal for unmarried women, and for widows with children, as well as reform of the law on child assault.

They wanted equal rights of guardianship for married men and women, equal pay for women teachers, and they challenged discrimination against women in the civil service. They issued a blacklist of MPs hostile to women’s interests, urging women, whatever their political loyalties, to vote against them.

Several new magazines directed at women appeared in the 1920s, though their titles –

Woman and Home

,

Good Housekeeping

–

88

clearly signal the limited expectations of their audience. But there were also dissenting voices, with a more radical take on women’s position, in

Time and Tide

, which was launched in 1920, its distinguished contributors including Virginia Woolf, Rebecca West, and Rose Macaulay. This magazine argued that women should act, independently, to put pressure on

all

the political parties to tackle women’s concerns, and it raised a whole range of women’s issues, including the position of unmarried mothers and of widows, and the guardianship of children. West wrote in 1925, as so often deliberately provocative:

I am an old fashioned feminist, . . . when those of our army whose voices are inclined to coolly tell us that the day of sex-antagonism is over and henceforth we have only to advance hand in hand with the male, I do not believe it.

Early 20th-centur

West was a socialist and a suffragist, an effective propagandist who always enjoyed a scrap – and who believed that women still had plenty to fight about.

y feminism

But her writing covers a whole range of subjects, and she is perceptive and often sharply witty. She mocks masculine sentimentality about women: ‘If we want to make every woman a Madonna we must see that every woman has quite a lot to eat’, she remarked, but she is equally scathing about idle upper-class women who spend days ‘loafing about the house with only a flabby mind for company’.

In later years Rebecca West went on to write very effectively on the trials of Nazi war criminals; and in the late 1930s produced a long and very interesting book on Yugoslavia. Her novels, on the other hand, reveal an unexpected and often cloying sentimentality about the relations between men and women.

Perhaps this sprang from what seems to have been an unhappy private life: she had an illegitimate child by H. G. Wells and, though they stayed together for a few years, she essentially 89

brought up her son Anthony alone. He later turned nastily on his mother, apparently without any understanding of what must have been a difficult time for her.

All through this period, the popular press, whether nervously or sarcastically, tended to portray the feminist as a frustrated spinster or a harridan; one journalist remarked that, because of war, many young women ‘have become so de-sexed and masculinised, indeed, and the neuter states so patent in them, that the individual is described (unkindly) no longer as ‘‘she’’ but ‘‘it’’ ’. Women teachers, as well as women in the civil service, sometimes had to fight against discrimination. The 1920s also saw the beginnings of economic recession and, as so often, women were the first to face unemployment.

But there were certainly more women being adequately educated, at schools and also at university level, thanks in large part to the work of Emily Davies (see Chapter 5). However, in

A Room of One’s Own

,

minism

Virginia Woolf, in her typically oblique way, suggested the ways in

Fe

which women were second-class citizens in Cambridge: she describes being barred from entering a famous library, and how she and a friend, a fellow in a women’s college, dined, not like the men on sole and partridge, but on gravy soup and beef. In 1935 another writer, Dorothy L. Sayers, gave in her novel

Gaudy Night

a much more generous and affectionate account – based on her own education at Somerville College, Oxford – of the integrity, high intelligence, and conscientious concern for other people shown by the women dons (even though she had to import her male detective to sort out a criminal problem for them). As one of her dons remarks, cheerfully, they have indeed achieved a great deal – and it has all been done by ‘pennypinching’.

The battle for legal, civil, and educational equality has been – and to some extent still is – a central element in feminism; but the movement has also highlighted the differences between the sexes, and asked for a new and deeper understanding of women’s special 90

needs as wives and mothers. One of the most interesting – and in the long run, most significant – episodes in the early 20th century concerned a subject that had rarely been publicly discussed, and which could still arouse bitter opposition: contraception. As early as 1877, the pro-birth control organization the Malthusian League had issued propaganda about ways of controlling conception; two of its most prominent members, Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh, were put on trial for publishing an American tract on the subject, called

The Law of Population

. (This was the same Annie Besant who became a vociferous supporter of the strike of female workers over conditions at the Bryant and May match factories in the 1880s.)

The Law of Population

was written by Margaret Sanger, who had worked as a nurse with women in the New York slums, as well as

Early 20th-centur

setting up a monthly magazine,

Woman Rebel

, which not only called for revolution but – apparently more dangerously – also offered contraceptive information. In a pamphlet called

Family

Limitation

, she argued that contraception enabled ‘the average

y feminism

woman’ to have ‘a mutual and satisfied sexual act . . . the magnetism of it is health-giving and acts as a beautifier and tonic’. Sanger left the United States the day before she was due to be tried under the Comstock Law, which, in 1873, had made it an offence to send

‘obscene, lewd or lascivious’ material through the mail. She arrived in Glasgow in 1914, then came to London in July 1915, where she met Marie Stopes.

In spite of their shared interests, their relationship was by no means easy. Stopes was a complicated and difficult woman. As a girl, she had been both clever and ambitious, and, encouraged by her father, was educated to university level, gaining a BSc. But – presumably like many other well-brought-up girls of the period – she knew almost nothing about sexuality. Nevertheless, her very prolonged ignorance does seem unusual; after a long, intense, but sexless love affair with a Japanese man called Fujii, she married a man called Reginald Gates. This marriage was never consummated, but it took 91

minism

Fe

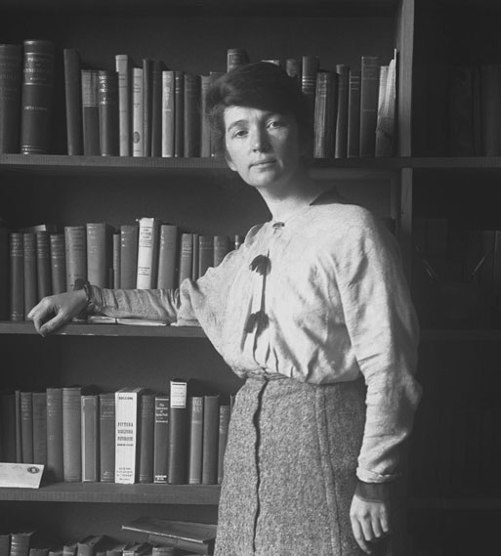

10. Margaret Sanger, a nurse working with women in the New York

slums, made contraceptive advice widely available – a very courageous

act at the time – and had to flee the country to avoid court action against

her.