Films of Fury: The Kung Fu Movie Book (20 page)

Read Films of Fury: The Kung Fu Movie Book Online

Authors: Ric Meyers

By the time New Line Cinema made a deal to distribute Chan’s new films in America, and Dimension Films arranged to screen some of his older movies, the audience that made

Star Trek

,

Star Wars

,

Superman

, and

Batman

famous were already well aware of Jackie’s talents. Now all he had to do was create new films for the international market that lived up to his past classics. Easier said than done.

“American stuntmen try to teach me how to fight,” Jackie recalled. “I ask them, ‘How long have you been fighting?’ Two years. I studied Northern Style ten years, Southern style five years, hapkido

, six months, karate

, four months, boxing three months…. ‘How long have you been in the movie business?’ Three years. I’ve been in the action movie business for more than forty years. Most people who choreograph martial arts films in the U.S. only know how to fight. They don’t know about their audiences, and the effects needed to excite that audience.”

Still, Double-Boy wasn’t giving up on his American dream. First came

Rumble in the Bronx

(1995), fueled by an exceptional New Line promotional campaign. It made more than thirty million dollars, a respectable sum for a film where the kung fu finale had to be scrapped because Jackie broke his ankle. It was infuriating. While Chan was used to being injured on his sets in some spectacular way, now his ankle was snapping after a mere hop from a bridge to a hovercraft. Even so, he merely had a sock painted to look like a sneaker, put it over his cast, and reworked the ending so it could be a car stunt instead of an extended kung fu fight.

Then, much to his fans’ dismay, Jackie discovered that he liked replacing his tiring, challenging, final, extended, fight scene with a car stunt.

Thunderbolt

(1995), a wild, aimless auto racing thriller that starred Jackie as an erstwhile

Speed Racer,

featured two great Sammo-choreographed fight scenes but little else to recommend it.

First Strike

(1996) was a surprisingly tepid spy saga.

Mr. Nice Guy

(1997) and

Who Am I

(1998) — both set in Australia — had some fine fights as well, but that hardly made up for their amateurish acting and feeble plotting.

The year 1998 saw Jackie Chan

’s American hopes under siege. His U.S. box office had been hurt by the re-editing, re-scoring, re-dubbing, re-titling, and re-releasing of his older movies in America. Chan’s movies kept making money, but not the kind of money they could have been making, and one American filmmaker was getting pretty fed up with it. So he took a script about a married couple of cops who bicker their way to find the abducted child of a Chinese diplomat, rewrote it to replace the married couple with a fast-talking, streetwise African-American cop and a straight-laced kung fu cop from China, recruited an actor from his previous film,

Money Talks

(1997), then went to Jackie with a promise: to make him as big in America as he was in the rest of the world.

Brett Ratner

was as good as his word, despite the fact that

Rush Hour

(1998) was only his second major feature film. But although Ratner loved Jackie’s Hong Kong films and was certain he could translate their joys into the “buddy cop” idiom, it seemed that Jackie didn’t like being just an actor, nor being at the mercy of co-star Chris Tucker

’s quick improvisational wit — especially in a language he had always been uncomfortable with. At first his worries seemed justified. Studio execs who viewed the footage, and critics who attended the premiere, gave the picture only a middling chance of success. Even the director himself was reported to have thought that the movie would probably gross only thirty million, tops.

But those who went to the movie its opening weekend knew different. In hundreds of cinemas across the country, the seats were filled with young and old, male and female, black, white, and Asian — and all of them were smiling. Rarely had any movie attracted such a cross section of filmgoers, and rarely had any movie pleased every one of them.

Rush Hour

turned out to be the movie Jackie Chan

had been promising for years — fast, funny, warm, action-filled entertainment with virtually no swearing and essentially no a

ctual violence. Instead, viewers were treated to an effective synthesis of Jackie’s trademarks: an inventive use of props as well as an amalgamation of kung fu, wushu, acrobatics, and imagination — all layered with Chan’s anti-Bruce approach (humor, showing pain, etc.).

The stars’ real-life distrust of one another and their own career ambitions blended perfectly with their characters’ motivations, and their well-honed performing skills only inspired each other to greater heights. Tucker’s mind and mouth aligned with Jackie’s brain and body, resulting in a consummate crowd pleaser.

Rush Hour

went on to gross more than two hundred million dollars, and instigate a series of sequels … each less effective than the last. And even though Jackie was happy to finally be king of the American hill, he far preferred it on his own terms. The British lease on Hong Kong had run out in 1997, so, as Hong Kong was returned to Chinese rule, Jackie Chan

returned to China.

From then until now, he has bounced back and forth between America and Asia, making films in both countries that have ranged from uninspired, though well-meaning, to merely agreeable. In 1999, there was

Gorgeous

, his middling remake of Kevin Costner

’s romantic comedy

Message in a Bottle

(1999), with some good fight scenes. There he showcased another on-going technique: the imaginative use of putting on, and taking off, his jacket as a martial weapon.

In 2000, he was back to America for a “wushu Western” with Owen Wilson

,

Shanghai Noon

(which begat the loosely limbed

Shanghai Knights

in 2003). In 2001, he had the anticlimactic, confusing

The Accidental Spy

in China and

Rush Hour

2

in the U.S. 2002 was a bleak year, indeed, giving rise to, arguably, Chan’s worst films: America’s

The Tuxedo

and China’s

The Medallion

. It was obvious that his fight scene prowess had reached a physical and mental crescendo. There was precious nothing new, even in the action.

Even Jackie realized he had scaled new lows, so he attempted a return to glory with the tough-minded (but weak-willed)

New Police Story

in 1994. But rather than find new ways of integrating kung fu, he merely ramped the emotional content up to eleven, seemingly crying every chance he got. The American weak-kneed

Around the World in 80 Days

remake during the same year didn’t help matters. 2005 saw Jackie in India for

The Myth

— another ultimately unsuccessful attempt to meld his kung fu with special effects. He tried to do a Chinese take on

Three Men and a Baby

(1987) in 2006 with the awkwardly structured (and awkwardly titled)

Rob-B-Hood

. 2007 was marred by the indifferent

Rush Hour

3

.

2008 was the best of Jackie times and the worst of Jackie times. As an example of what American studios can do badly, Lionsgate and The Weinstein Company hired the three greatest kung fu film minds in the world — stars Jackie Chan

, Jet Li

, and choreographer Yuen Wo-ping

— then apparently told them how to do what they did better than anyone else.

The Forbidden Kingdom

is supposedly a film created to honor kung fu, but it has virtually no kung fu in it. There’s “martial arts,” sure, but from all the balance-robbing-wires, and stiff-armed, stiff-legged, muscle-driven, hip-less action going on, it certainly appeared that someone told the trio to do “mixed martial arts … that’s what all the kids are digging these days.”

There’s a joke in Jiang Hu

: know what mixed martial arts is mixed with? Crap.

It’s just a joke.

Anyway, the finished film is a mass of misplaced homages, messy battles, ham-fisted story development, and missed opportunities by the dozens. The nominal hero doesn’t even learn to avoid a bully’s kick, despite the fact that it is used in the exact same way repeatedly throughout the film. When he finally does counter it, it’s with a ridiculously self-damaging defense that has as much to do with kung fu as a swan has to do with a dead cow.

Meanwhile, on the other side of town, DreamWorks Animation decided that their first cartoon that wasn’t created to undercut or satirize Disney/Pixar would be about a

Kung Fu Panda

. More about that in a later chapter, but suffice to say that Jackie Chan

did the voice of the Monkey, and the Chinese Government chided its own cinema industry for not coming up with something as excellent and accurate as it.

Jackie kept busy in 2009 with the well-intentioned

Shinjuku Incident

, a crime thriller devoid of all kung fu, the idolizing mock documentary

Looking for Jackie

(aka

Jackie Chan

and the Kung Fu Kid

aka

Jackie Chan

Kung Fu Master

), and

The Founding of a Republic

, the Chinese Government’s sixtieth anniversary latter-day propaganda film. Chan started 2010 with

The Spy Next Door

, a demoralizing Disney-produced, agonizing American family comedy. But then came the summer and the Will Smith

-produced remake of

The Karate Kid

, starring his son Jaden and Jackie in the “Mr. Miyagi” role.

Although the Smiths had lobbied for a title change (and, indeed, the film is known as

The Kung Fu Kid

elsewhere in the world), the studio marketing department demanded “brand recognition” — even though calling this remake

The Karate Kid

would be like calling the tale of a young baseball player

The Football Kid

. Nevertheless, the Harald Zwart

-directed remake, although overlong and featuring another fairly ludicrous final defense, is honorable and enjoyable in the extreme, featuring one of Jackie’s best performances and an extended central training travelogue sequence that’s worth the price of admission.

It was also abundantly clear that, unlike certain aforementioned films I could rename, the kung fu on screen was left up to Jackie. Naturally his veteran fans got a little boost from seeing his “jacket-on, jacket-off” technique return as a fitting, effective, accurate replacement of the witty “wax on, wax off” of the original (although I’m sure the ludicrous final move would not have been Chan’s first choice … but what American would go for a subtle devastating technique when they can do a circus aerialist routine?). Happily, the film was a surprise box office hit, and a sequel was planned.

As of this writing Jackie Chan

is still considered the reigning emperor of kung fu films, despite the fact that he is planning to slowly phase out his on-screen involvement in the genre — but not before two farewell productions: the prequel

Drunken Master 1945

, and his ultimate statement in kung fu films,

Chinese Zodiac

, which is about … surprise, surprise … the illegal selling of Chinese antiquities. Although he will always be mentioned immediately after Bruce Lee

, he has secured his legacy as the anti-Bruce, remaining a vitally important pioneer, a welcome diplomat, a generous philanthropist (with a specialty for education), and an influential ambassador for all good things.

“Before, when I made a movie, it was for money,” Jackie told me. “But now when I make a movie, it is my craft. Money comes second. These movies are my babies. To me, movies are my life.”

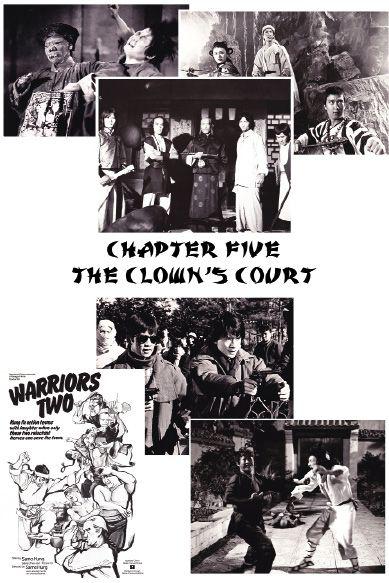

Picture identifications (clockwise from upper left):

Sammo Hung

in

Spooky Encounters

; Lam Ching-ying

, Chung Fat, Li Hai-sheng

, Fung Hak-on

, and Yuen Mao in

The Magnificent Butcher

; Moon Lee

, Yuen Baio

, and Mang Hoi

in

Zu Warriors of the Magic Mountain

; Sammo in

The Dead and the Deadly

, Yuen Baio and Jackie Chan

in

My Lucky Stars

;

Warriors Two

.

J

ackie Chan

’s ascension to the top of the Hong Kong cinematic heap had no real precedent in terms of speed and strength. When

Bruce Lee

burst upon the scene, it came as a total surprise. No one had done the kind of kung fu he was displaying. But Jackie’s way had been prepared for — by Bruce and, especially, Liu Chia-liang

, who had conceived the kung fu comedy Jackie perfected. So, by the time Chan did his

Drunken Master

thing, it seemed a welcome, subconsciously anticipated, delight — as if even the audience was his appreciative collaborator.

Although some attributed the success of

Eagle’s Shadow

and

Drunken Master

to novice director Yuen Wo-ping

, it became rapidly apparent that these films’ winning formula was more Chan than Yuen. Wo-ping, born in 1945, and an experienced stunt coordinator, performer, and kung fu choreographer since 1971, subsequently displayed a much rougher, more bizarre bent than Jackie.

Following the success of his first two, Jackie-starring, films, Yuen instituted The Wo Ping Film Company to make a series of increasingly crazier films. He started by cementing his father’s fame with

Dance of the Drunken Mantis

(1979), a semi-sequel in which Simon Yuen

Siu-tien’s “Sam the Seed” (aka Beggar Su) discovers his son, Foggy, only to almost lose him to a vengeful drunken mantis fist fighter named Rubber Legs (Huang Jang-li

).

Beyond the odd story, Yuen filled the crude-looking film with family, as well as truly weird comedy characters and situations. He also gave the “Jackie” role to his brother Sunny Yuen Shun-yi

, who, although an exceptional martial artist, was hardly what anyone would call classically handsome. He also cast Sunny as the star of

The Buddhist Fist

(1980), another weird, cheap-looking, kung fu-filled effort that combined truly peculiar comedy with a nasty plot about a masked killer rapist (played by Tsui Siu-ming

, a Sammo Hung

look alike who has had an extensive, eclectic career).

Speaking of Sammo, he and Golden Harvest

came calling on Wo-ping to essentially say, “You know what you did for Jackie in

Drunken Master

? Could you do that for me, please?” The request was not unnatural. Fans had been waiting years for Sammo to play rotund Butcher Wing, one of Huang Fei-hong’s favorite disciples (who, in real life, was sifu to Liu Chia-liang

’s father). So Wo-ping and his own father set to work on

The Magnificent Butcher

(1979), which promised to do Jackie’s films one better by having

Kwan Tak-hing play the “real” Huang Fei-hong in it. Then, tragically, midway through production, Simon Yuen

passed away, requiring a hasty recasting of veteran character actor Fan Mei-sheng

in the Sam Seed role.

Although Fan was famous for his many Shaw Studio performances (such as Black Whirlwind in

All Men Are Brothers

), he was hardly as venerated as Simon. Wo-ping attempted to compensate by creating some of the best, and most memorable, Huang Fei-hong scenes in history (including a calligraphy fight that ranks amongst the best ever conceived), but, as good as it was,

Magnificent Butcher

didn’t do for Sammo what

Drunken Master

did for Jackie.

Even so, it did great, so naturally, it was Third Brother Yuen Baio

’s turn to say “please?” That resulted in

Dreadnaught

(1981), Kwan Tak-hing’s final Huang Fei-hong performance, where-in a young launderer (Baio) runs afoul of a psychotic murderer (Yuen Shun-yi

again) hiding out in a Peking Opera

troupe. Wo-ping tries to do the calligraphy scene one better with a “mad tailor” sequence in which an assassin tries to kill Huang while measuring him for a suit, but it didn’t cut it (all puns intended).

Those responsibilities to Jackie’s classmates concluded, Yuen returned to his predilections, leading to two of the strangest kung fu films ever foisted by a major talent.

The Miracle Fighters

(1982) and

Taoism

Drunkard

(directed by Wo-ping’s brother Cheung-yan

in 1984) have to be seen

not

to be believed. Featuring much of the family as always, it also portrayed such things as a “banana demon” — a black, Pac-Man-like, ball on legs with antennas and a watermelon-slice-shaped, chomping mouth lined with shark teeth.

Whether the film is wacky or wonderful, Wo-ping approached the kung fu choreography in the same way. “I know the plot from start to finish,” he explained, “how it progresses and develops. I study how many action scenes, and work out which should be big ones and which should be small ones. Each scene should have its special theme, and they should progress and develop the way the rest of the film does.” But within a year, he would find a new path amongst his peers via a developing appreciation of taichi

. His directing

Drunken Tai Chi

in 1984 would announce his intentions, as well as introduce a new star to the world: Donnie Yen

. But more on him later.

Ironically, Simon Yuen

’s final appearance as Sam Seed wasn’t directed by Yuen. It was in

World of Drunken Master

(1979), which was directed by Joseph Kuo Nam-hung

. Simon appeared only in the prologue — replaced for the bulk of the film by Li Yi-min

as “young Beggar Su.” Joseph Kuo (aka Kuo Qing-chi) is generally considered the monarch of Taiwan martial art moviemakers, which was a bit like being one-eyed amongst the blind. As mentioned earlier, Taiwan produced literally thousands of genre films, so any that even approached Hong Kong quality were considered genius. Kuo approached approaching genius throughout his (unsurprisingly) prolific career. He made dozens of films in a variety of genres, but his best known kung fu efforts include

The Blazing Temple

(1976),

The Seven Grandmasters

(1978),

The Mystery of Chess Boxing

(1979), and

The 36 Deadly Styles

(1979) — while his

Swordsman of all Swordsmen

(1968) and

The 18 Bronzemen

(1978) were landmarks in Taiwan cinema.

By that time, he had hit upon a winning kung fu formula. Using brothers Jack Long Sai-ga

and Mark Long Kwan-wu

(as well as Corey Yuen Kwai

and Yuen Cheung-yan

) as choreographers, he filmed fight after fight, and plotline after plotline, and then pieced them together until they filled ninety minutes. Anything left over was saved for the next ninety-minute slot. However disjointed his stories, there was always ample entertainment value in the fighting.

The same was true of Lee Tso-nam

, another Taiwan moviemaker who rose to the top. He co-starred in Kuo’s

Swordsman of All Swordsmen

, and was assistant director on

The Big Boss

— learning his mentors’ lessons well. He became a full-fledged director in 1973, and quickly made his name with such fun, catch-all, kung fu films as

The Hot, The Cool and The Vicious

(1976),

Eagle’s Claw

(1977), and

Fatal Needles vs. Fatal Fists

(1978). They were also elevated by the assured, pleasantly complex choreography by Tommy Lee Gam-ming

, who learned his craft in a Taiwanese Opera School, and was exceptional at designing multi-group fight scenes of eight or more, so the camera could move seamlessly from one group of fighters to the next.

All these starred Delon Tan (aka Tan Tao-liang

) and Don Wang Tao

(who was once groomed as a “new Bruce Lee

”). The Bruce connection was not lost on Tso-nam, since he also made some of the most enjoyable “Bruce Clone” films, such as

Exit the Dragon,

Enter the Tiger

(1976, with Bruce Li),

Chinese Connection 2

(1977, with Bruce Li),

The Tattoo Connection

(1978, with Jim Kelly

), and

Enter the Game of Death

(1978, with Bruce Le).

Both Kuo and Tso-nam benefited greatly by filling their films with the best acting and fighting talent they could find. Their cast lists are a who’s who of superior supporting players, including Ku Feng

, Bolo, Bruce Leung Siu-lung

, Li Hai-sheng

, Philip Kao Fei

, Chen Kuan-tai

, Shoji Kurata

, Lo Lieh

, and Chang Yi

. If you watch kung fu movies at all, you’ll see these guys again and again.

But beyond the relative quality of their work, Joseph Kuo and Lee Tso-nam

assured their international fame through a stroke of luck. Both made deals with pioneering exporter Ocean Shores Limited

to sell their flicks internationally for the home entertainment market, catching the first wave of American interest in the genre. While the rest of Hong Kong was belittling kung fu films, Ocean Shores and its farsighted boss Jackson Hung

, was instituting a ground-breaking Los Angeles office (run by Matthew Tse

), and selling its made-in-China videotapes to whoever would buy or rent them. They even instituted a then-revolutionary rent-by-mail program for the individual American kung fu movie fan.

Although they tried to follow fads (shoving the word “ninja

” into any title they could) and swallowed a lot of producers’ propaganda (that Americans didn’t want widescreen or subtitles), many Asian filmmakers might never have been known on these shores without Ocean Shores. Following quickly into the fray was Tai Seng

Entertainment — its American office run by general manager Helen Soo

— who snapped up many VHS Ocean Shores videotapes to make the transition onto DVD. This included Sammo Hung

’s seminal

The Victim

(1980), not to mention the best independently-produced Liu Chia family films (such as 1977’s

He Has Nothing But Kung Fu

, 1978’s

Dirty Kung Fu

, 1980’s

Fists and Guts

, and 1984’s

Warrior

from Shaolin

).

Back in the early 1980s, Jackie Chan

’s Peking Opera

school senior, Sammo, was chafing a bit over his “younger brother’s” mega-success. Born in 1950 and nicknamed after the famous Chinese cartoon character “Sam-mo” (meaning “three hairs”), Hung Kam-po enrolled at the Peking Opera School at the age of ten, started appearing in films at age eleven, then became a freelance stuntman at sixteen. Show business, it seemed, was in his blood.

“I was born into a movie family,” he told me. “My father and mother both worked in the Hong Kong movie industry. I learned karate

, judo

, taekwondo

and hapkido

, which were the basic needs of my profession then. I worked for all the studios. Even though they didn’t look real on screen, I had to spend a lot of time preparing for the fight scenes. It was old-fashioned, traditional kind of kung fu before the stardom of (Jimmy) Wang Yu

.

“Actually, I like every kind of kung fu. I didn’t think about which one was better than the other, I just learned everything I could. [Style] names were not important. The most important thing was how to defeat somebody. When I was young, things could get very violent. I had a lot of fights. That’s how I got my facial scars. I was in a nightclub, and some drunk got so angry that I did a flip on the dance floor. When I got to my car, there were three people waiting to ambush me. One comes up behind me and swings a broken bottle into my face. I’m actually very lucky. If it had gone into my eyes, that would have been it. Even so, it took twenty-three stitches.”