Financial Markets Operations Management (21 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

In this chapter we have seen how the buy-side and sell-side institutions participate in the markets. We examined how investors can access the markets and the intermediaries who assist in this. There are different types of investor, from private investors (retail) to institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies that can either invest their own assets or appoint fund managers to do this for them on a discretionary basis.

Banks play a vital intermediary role whether on a commercial, investment, private or central banking basis.

The financial markets should be regulated in order to provide investors with a transparent and fair means to invest. We therefore have domestic regulators that consider local requirements and regional regulators for a broader geographical/political region such as Europe.

There are trade associations that focus on specific markets (e.g. the FSA in Japan), products (e.g. the ISDA for derivatives) and intermediaries (e.g. the various central securities depositories associations).

Finally, we looked at regulated and OTC markets where the transactions are executed. We have seen that the traditional Stock Exchanges (where securities are listed, derivatives created and both are traded) are being challenged by alternative platforms such as Multilateral Trading Facilities, Alternative Trading Systems and Electronic Communications Networks. Furthermore, additional platforms are being introduced as a result of regulatory changes in the USA and Europe (i.e. Organised Trading Facilities and Swap Execution Facilities) in order to transition OTC derivatives onto more transparent, regulated platforms.

Clearing Houses and CCPs

Part Two of this book will take you through the post-trade processing of the financial instruments that you looked at in Chapter 2: Financial Instruments. We will do this by considering market infrastructures and trade lifecycles in the ways outlined in

Table 5.1

.

TABLE 5.1

Market infrastructures and trade lifecycles

| Market Infrastructure | Trade Lifecycle |

| (a) Clearing houses and CCPs | Clearing |

| (b) Central securities depositories | Settlement and settlement fails management |

| (c) Custody intermediaries | The role of the custodians |

It is not possible to cover every financial product in every market; this would indeed be a very large book! Instead, we will look at the major types of financial product with a brief description of the appropriate clearing system, depository and custody intermediaries; in particular, we will look at:

- Equities;

- Government bonds;

- Eurobonds;

- Exchange-traded derivatives (futures and options);

- Centrally cleared OTC derivatives (interest rate swaps);

- Non-cleared OTC derivatives (forward rate agreements).

In Section 5.5 at the end of this chapter you will find some useful information sources for infrastructural organisations such as the clearing houses, depositories and custodians together with statistical information. You might like to bookmark these organisations' URLs so that you can access their websites without too much trouble.

For many people, the terms

clearing

and

settlement

are synonymous. This is not strictly true; clearing is the first step in the post-trade process that leads to settlement.

If only buying a new property was this straightforward! It does, however, make a good analogy to our world of equities, bonds and derivatives, as shown in

Table 5.3

.

TABLE 5.3

Property and securities analogy

| Step | Analogy |

| 1. Find the property | Price discovery (Front Office) |

| 2. Make an offer on your chosen property | Transaction execution (Front Office) |

| 3. Preliminary activities | Clearing (Operations) |

| 4. Contract exchange date | Settlement (Operations) |

| 5. Obtain ownership | Registration of a change of legal and beneficial ownership (Safekeeping) |

Let us define what we mean by the terms

clearing

and

settlement

, according to the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (CPSS):

1

In Chapters 7 to 9, we will explore clearing and settlement both in terms of structure and how these two overall processes work.

The CPSS defines a clearing house as:

The key words and phrases in this definition are shown in

Table 5.4

.

TABLE 5.4

Clearing house definition

| Extract | Implications |

| Central location | There might be one clearing house per financial instrument in any one location, or There might be one clearing house for all financial instruments in any one location. |

| Institutions agree to exchange | This is an agreement rather than the actual exchange itself. |

| Institutions settle ⦠at a designated time based on the rules and procedures ⦠| The clearing house dictates how and when financial instruments are processed. |

| The clearing house may assume significant counterparty, financial or risk management responsibilities | This is very true; we will explore this in more detail when we consider central counterparties (CCPs). |

Details of executed transactions in financial instruments are passed down from the relevant securities/derivatives exchange to the appropriate clearing house, and typically both the buyer and seller will confirm these transactions by submitting receive and delivery instructions respectively.

The clearing house will then take the necessary actions in order to make the transactions available for eventual settlement. In accordance with local practice, settlement is intended to take place at some predefined time after the trade date. Depending on the financial instrument and the location in which it was traded, typically settlement can take place from the trade date itself to one or more business days after the trade date. Settlement on the trade date is referred to as trade date T+0. Settlement three business days after the trade date is referred to as T+3.

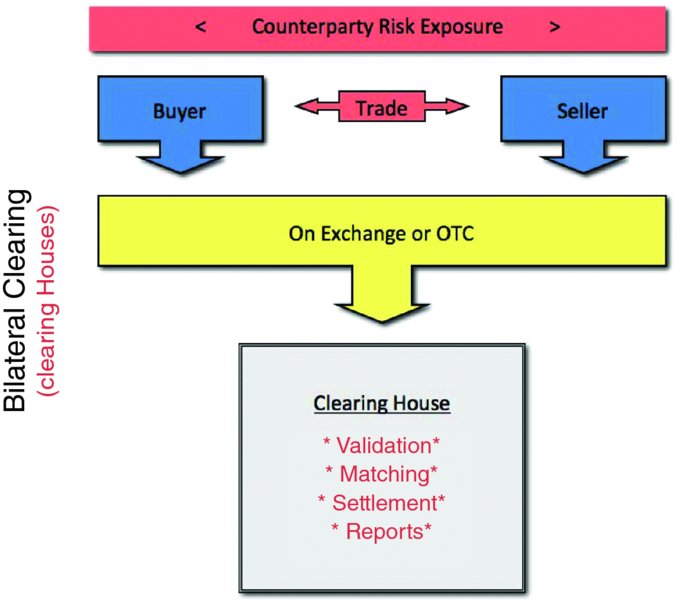

In the clearing house model (see

Figure 5.1

), the clearing house will perform the following activities:

- Validate incoming instructions from the buyer and seller (or their agents). The validation process ensures that the instructions are potentially correct (e.g. that the board lot size matches with the reference database, the price is within a prespecified tolerance and the correct amount of accrued interest accounted for).

- Match the buyer's receive instructions to the seller's delivery instructions. If the details in both instructions agree, then the clearing house can assume that these instructions refer to the same underlying transaction and that both parties agreed to the economic terms. Where instructions do not agree, the clearing house will mark these with the status “Unmatched”. The clearing house will not allow any unmatched transactions to go forward for settlement and both the buyer and the seller will be required to investigate the reasons why their instructions do not match.

- The clearing house will judge whether there are sufficient assets to enable settlement to take place. This includes sufficient cash (or credit or access to financing) for the buyer and asset availability for the seller.

- On the intended settlement date the clearing house will allow the transaction to settle, subject to availability, and will pass details of this to a third party where the transaction will actually settle. This third-party entity is known as a

central securities depository

.

FIGURE 5.1

Clearing house model

Please note that in this model the clearing house is acting as a facilitator and does not assume any credit risk in terms of the buyer and the seller. We refer to this type of credit risk as

counterparty risk

and it is the risk that one counterparty or another will not be in a position to honour its obligations concerning the transaction or transactions executed between the two counterparties. The counterparty risk remains with both counterparties until such time as the transaction is finally settled.

The following organisations are examples of this particular model:

- CETIP (Brazil);

- CCASS (for exchange trades executed on the Isolated Trade System and non-exchange trades) (Hong Kong);

- Saudi Arabian Clearing House;

- Strate (South Africa);

- Fixed Income Clearing Corporation: Mortgage-Backed Securities Division (USA).

The CPSS defines a central counterparty (CCP) as:

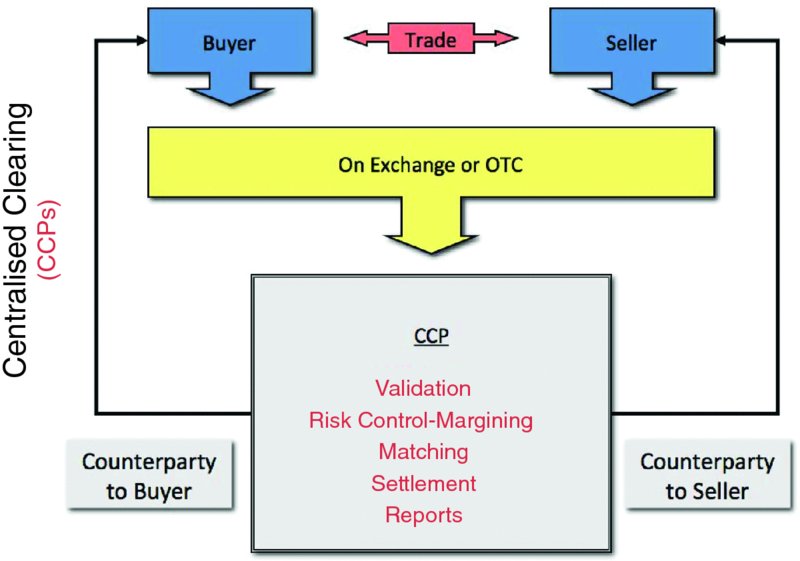

We saw above the role the clearing house plays. It is similar to that of a CCP with one key difference: the CCP novates the transactions and assumes the counterparty risk of the buyer and, separately, the seller. Once a transaction is novated, the original counterparty risk exposure between the buyer and seller is eliminated.

What does this change in counterparty risk mean for the CCP? In the clearing house model, if one party defaults before settlement, the risk lies with the counterparty to that trade. By contrast, in the CCP model (

Figure 5.2

), that risk exposure now rests with the CCP itself. The CCP, therefore, must have very robust risk-mitigation procedures in place otherwise there is the risk that a default, or a series of defaults by more than one party, might cause the CCP to default.

FIGURE 5.2

Central counterparty model

On 15 September 2008, the American investment bank, Lehman Brothers, failed.

2

The reasons why are outside the scope of this book. However, for our purposes, one of the key issues that arose from this failure concerned the bank's OTC interest rate swap positions with a notional value of USD 9 trillion. This portfolio consisted of 66,390 trades across five major currencies.

3

LCH.Clearnet, together with member firm participation, had, by 3 October 2008, successfully auctioned off the portfolio without any damage to the CCP.

CCPs manage their risk mitigation by:

- Maintaining policies on the many different types of risk, e.g. counterparty credit risk, business risk, operational risk, regulatory and compliance risk;

- Applying a margin to CCP member firms' transactions;

- Maintaining default funds which are sufficient to withstand the default of one or more members;

- Protecting client positions by transferring them to another clearing member if a clearing member firm defaults;

- Collecting eligible/acceptable collateral to which appropriate haircuts have been applied;

- Covering the relationship between CCP and member firms through a rule book.

All of the above should be regularly stress-tested and updated as market conditions change.

In the event that a member firm defaults, its CCP should apply a “waterfall” line of financial defence, as shown in

Table 5.5

.

TABLE 5.5

CCP â line of financial defence

| Defaulting member's margin (e.g. initial margin, variation margin, etc.), then, if insufficient ⦠|

| Defaulting member's contribution to a default fund, then ⦠|

| The CCP's reserve fund, then ⦠|

| Clearing fund contribution of other members, and finally ⦠|

| Equity of the CCP. |

We can observe that the first line of defence is the defaulting member's own financial resources followed by the CCP's and other members' reserve funds. Finally, the CCP's equity acts as the last line of defence.

The following are examples of the CCP model:

- ASX Clear (Australia);

- CDS Clearing & Depository Services (Canada);

- China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation

4

(China); - Eurex Clearing (Germany);

- LCH.Clearnet (France, Belgium, Italy, Netherlands and UK);

- CCASS (for trades executed on the Exchange Trades-Continuous Net Settlement System) (Hong Kong);

- Japan Securities Clearing Corporation (Japan);

- National Securities Depository (Russia);

- SGX-Central Depository (Singapore);

- OMX Derivatives Markets (Sweden);

- SIX x-clear (Switzerland);

- National Securities Clearing Corporation (USA).