Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (38 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

This game was easily recognizable by those diligent investors that read Tenet’s financial reports. As presented in the box, the company clearly disclosed in its March 2004 10-Q that it planned to keep $394 million in receivables in connection with the sale of 27 hospitals. Careful investors were not misled into thinking that this gimmick actually produced sustainable CFFO.

TENET’S DISCLOSURE ABOUT THE SALE OF HOSPITALS, 3/04 10-Q

Because

we do not intend to sell the accounts receivable

of the asset group, except for one hospital, these receivables, less the related allowance for doubtful accounts, have been included in our consolidated net accounts receivable in the accompanying condensed consolidated Balance Sheets. At March 31, 2004,

the net accounts receivable for the hospitals to be divested aggregated $394 million.

[Italics added for emphasis.]

Looking Back

Warning Signs: Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals

• Inheriting Operating cash inflows in a normal business acquisition

• Companies that make numerous acquisitions

• Declining free cash flow while CFFO appears to be strong

• Acquiring contracts or customers rather than developing them internally

• Boosting CFFO by creatively structuring the sale of a business

• New categories appearing on the Statement of Cash Flows

• Selling a business, but keeping the related receivables

Looking Ahead

The next chapter completes our discussion of shenanigans that companies use to inflate operating cash flow. Unlike the first three Cash Flow Shenanigans, which all involved shifting the “bad stuff” out and pushing the “good stuff” in, the fourth one discusses onetime unsustainable boosts to operating cash flow—not shifting or pushing from one section to another, but just plain old one-time boosts that investors should not expect to see in future periods.

13 – Cash Flow Shenanigan No. 4: Boosting Operating Cash Flow Using Unsustainable Activities

With local versions in more than 100 countries, the hit game show

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

is one of the most internationally successful television franchises of all time. The game is alluringly simple: contestants are asked up to 15 trivia questions. Answering all questions correctly will win the grand prize; however, if the contestant gives one wrong answer, he or she goes home.

If a contestant is struggling with a question, the rules allow for the use of a “lifeline.” For example, one lifeline allows the contestant to ask an expert for help, and another polls the studio audience for its opinion. These lifelines can prove very valuable and often keep struggling contestants afloat. However, they must be used judiciously, since there are just three of them, and once they’re gone, they’re gone.

Similarly, struggling companies often use valuable “lifelines” to help them keep their cash flow afloat. Just as in the game show, it is often wise and certainly legitimate for companies to use these lifelines. Unlike in the game show, however, companies may fail to disclose the use of these nonrecurring cash flow lifelines. It is up to you to spot them, because once they’re gone, they’re gone.

In Chapter 13 we discuss four unsustainable lifelines that companies use to boost their cash flow from operations (CFFO).

Techniques to Boost Operating Cash Flow Using Unsustainable Activities

1. Boosting CFFO by Paying Vendors More Slowly

2. Boosting CFFO by Collecting from Customers More Quickly

3. Boosting CFFO by Purchasing Less Inventory

4. Boosting CFFO with One-Time Benefits

1. Boosting CFFO by Paying Vendors More Slowly

Want to save a little more cash this year? Use your “delay payments” lifeline: wait until the beginning of January to pay your December bills. If you push your payments out a month, your end-of-year bank balance will be higher, and it will cosmetically seem as if you generated more cash this year. However, you certainly would not be under the delusion that you had found a recurring way to grow your cash flow each year; rather, you would realize that this was a one-time benefit. To grow your cash flow again next year, you would have to push two months’ worth of payments into the following January.

Your “delay payments” lifeline may be a helpful cash-management strategy, and there is certainly nothing wrong with holding your money a month longer. In the same way, it is completely appropriate for a company to take longer to pay back its vendors and reap the immediate cash-management benefits. However, just like you, companies cannot continue to delay payments into eternity. The cash inflow from pushing out payments (i.e., an increase in payables) should be considered a one-time activity, not a sign that the company has found a lasting way to generate more cash. While this may seem like common sense, you would be surprised at how many companies tout their CFFO strength and forget to mention their little secret: that they increased CFFO by stringing out vendors and not paying them in a timely fashion.

Home Depot Squeezes Its Vendors

Just days after losing an internal management succession battle to replace the legendary Jack Welch at GE, Bob Nardelli’s consolation prize was the top job at The Home Depot Inc. Appointed in December 2000, Nardelli immediately was hailed as the master operating executive that the unruly home improvement retail chain desperately needed. The board loved his GE pedigree and rewarded him right off the bat with an extremely generous compensation package. And Nardelli definitely knew how to please. In his first year on the job, he more than doubled CFFO—from $2.8 billion to nearly $6 billion. Investors who were not too worried about the details were thrilled.

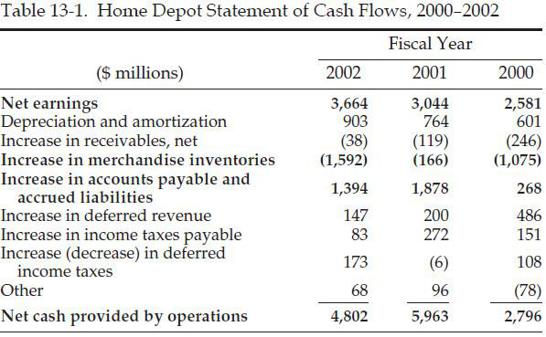

This cash flow growth, however, would prove to be unsustainable and unrelated to increasing sales at the business. In that first year, Nardelli did a masterful job of redefining the way Home Depot did business with its vendors. Specifically, the company started treating them very badly by paying them much more slowly. By the end of fiscal 2001, Home Depot had successfully stretched out accounts payable to 34 days from 22 the year earlier. The company’s Statement of Cash Flows (SCF) (Table 13-1) reveals that this seemingly small change in accounts payable was the primary driver of the company’s impressive cash flow growth. Another large component of CFFO growth was a decrease in the amount of inventory at each store (as we discuss later in this chapter).

Okay, mission accomplished for 2001. The next year, Home Depot was faced with the challenge of improving upon an incredible 2001. In order to grow CFFO again, however, the company first would have to replicate the 2001 boost that it would no longer receive in 2002. The company was able to stretch payables again in 2002, but not to the extent of the prior year (as payables reached 41 days from 34 days). CFFO for 2002 fell to $4.8 billion from $6.0 billion in 2001.

Accounting Capsule: Days’ Sales of Payables (DSP)

Days’ sales of payables (DSP) is generally calculated as follows:

Investors should analyze payables in terms of days’ sales, in much the same way that they analyze receivables (days’ sales outstanding, or DSO) and inventory (days’ sales of inventory, or DSI). An increase in DSP means that the company is paying off its payables over a longer period of time. A decrease in DSP means that the company is paying its bills more quickly.

Investors should note that Nardelli’s cash-management techniques certainly were not inappropriate and seemed beneficial to the company’s operations. The takeaway here, however, is that the $3 billion increase in CFFO during 2001 should have been viewed as nonrecurring. Alert investors would have correctly anticipated that CFFO would shrink in 2002.

Watch for an Increase in Payables.

An increase in payables relative to cost of goods sold (COGS) tells you that the company has probably stretched out its payments to vendors. Assess the extent to which CFFO growth is derived from stretching out payments to vendors and consider that amount an unsustainable boost that is unrelated to improved business activities.

Look for Large Positive Swings on the Statement of Cash Flows.

A quick review of Home Depot’s CFFO in 2001 shows that improvements in accounts payable and inventory were the primary drivers of CFFO growth. (See Table 13-1.) In the following year, it is evident that Home Depot’s inability to sustain that improvement was the primary source of CFFO deterioration.

Be Alert When Companies Use Accounts Payable “Financing.”

Auto parts retailers Advance Auto Parts, AutoZone, and Pep Boys all used bank loans to pay their vendors in 2004 (think of these arrangements as accounts payable “financing”). While the arrangements were essentially identical at all three companies, interestingly, each company recorded the cash flow impact differently. According to a report by the Center for Financial Research and Analysis (CFRA), Advanced Auto Parts recorded its loans as a Financing activity, AutoZone recorded them as Operating, and Pep Boys used a curious hybrid approach—inflows as Operating, but outflows as Financing. We believe that Advanced Auto Parts’ approach makes the most economic sense, since these arrangements are essentially financing activities.

This anecdote shows the enormous management discretion available in classifying a fairly straightforward transaction on the Statement of Cash Flows. In order to properly compare cash flow generation at these competitors, investors must adjust for this difference in policy. Each company provided sufficient disclosure to understand its SCF classification. Diligent investors would have used those disclosures to reflect both sides of the loan transaction (inflows and outflows) as Financing, not Operating.

Tip:

Accounts payable is a relatively straightforward account. If you see a discussion of accounts payable that is longer than a couple of sentences, there is probably something in there that you want to know (for example, accounts payable financing arrangements).

Watch for Swings in Other Payables Accounts.

Accounts payable is not the only obligation that companies can use to manage their cash flow. CFFO can be influenced by the timing of payments on many liability accounts, including tax payments, payroll or bonus payments, and pension plan contributions. Consider how Callaway Golf Company’s tax situation resulted in unsustainably strong CFFO in 2005.

Callaway spent the off-season working on its long game. The dedication seemed to pay off. In 2005, Callaway drove its CFFO up to $70.3 million—quite an improvement from the $8.5 million duff in 2004. A quick check of the Statement of Cash Flows reveals that CFFO growth came from an improved swing—that is, a $55.8 million “swing” in the impact of tax payables and receivables (apparently as a result of net tax refunds and settlements). It should not have been too rough for investors to spot this tax swing on the Statement of Cash Flows and deduce that Callaway’s strong CFFO growth would not recur.