First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam (33 page)

Read First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam Online

Authors: Daniel Allen Butler

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027130

BOOK: First Jihad: Khartoum, and the Dawn of Militant Islam

5.59Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Events reached their inevitable climax as past, present, and future—the Sudanese rebellion, Gordon’s defense of the city, the Mahdi’s revolt, the mission of the Relief Expedition—all came together in the early morning of January 26, 1885.

In the still grayness of the pre-dawn, Faraz Pasha, an Egyptian lieutenant whose loyalty Gordon had doubted, opened the main gates of the city.

Forewarned of his actions, the Mahdi’s army was waiting below the walls, and when the portal was opened, rushed in and spread out down the streets and alleys of Khartoum.

Exhausted and weakened by months on reduced rations, the defenders could put up only a feeble resistance.

Soon they were overwhelmed by a flood of Arab warriors, hacked to death by scimitars or run through by Dervish spears.

It took three hours for the Mahdi’s followers to overrun the whole of the city, and even as they were advancing toward the Governor’s Palace the looting, plunder, rape and murder had begun.

Shrieks and screams, pleas for mercy or forgiveness, cries of agony and despair, sounded down the alleys and streets.

The Ansar were making good on the Mahdi’s promise of a torrent of blood in Khartoum once it fell.

Gordon himself had been sleeping when the Mahdi’s army broke into the city.

The sound of gunfire awakened him, and he dashed up to the roof, where he saw a mob surging toward the palace.

For a while he was able to hold them off with a Maxim gun mounted there, but eventually the crowd got so close to the building that he couldn’t depress the muzzle sufficiently to fire on them.

He then went back to his quarters, quickly changed into the white uniform by which he was known throughout the city, buckled on his sabre, and picked up two revolvers.

Stepping out onto the head of the stairs leading up from the courtyard, he waited for the Arabs to burst in.

Gordon had long debated with himself what his action should be at the supreme moment.

He had once told Sir Evelyn Baring, “I shall never be taken alive.” Now that moment had come.

What happened next is still debated.

The Mahdi’s followers had hesitated to enter the Governor’s Palace, fearing both the possibility of mines on the palace grounds and the chance that the entire building might blow up in their faces if Gordon indeed lit the fuse to the tons of powder stored in the palace cellars.

A few of the braver among them finally charged into the palace and were quickly followed by hundreds more.

The Palace Guard, fighting desperately and selling their lives dearly, were massacred.

When the Arabs at last pushed into the courtyard, they found Gordon waiting, still at the head of the stairs leading up to his quarters.

One version of the next few moments has Gordon rushing down the stairs, charging into the midst of his attackers, emptying both revolvers before drawing his sword and hacking at them until he was overwhelmed in a flurry of spear thrusts.

Another version tells of Gordon fleeing the Governor’s Palace and attempting to reach the American Consulate, where, it is said, he believed he would find sanctuary.

As this story has it, Gordon was recognized by the Arabs while still in the streets of the city and was killed in a flurry of rifle fire.

The most popular telling of how General Gordon met his end has him standing motionless at the top of the steps of the Palace courtyard, his icy blue eyes staring down his assailants, who suddenly halted their headlong rush when they caught sight of him.

For a moment, there was a silence as still as death, as Gordon surveyed his attackers.

They were led by four of the Mahdi’s fiercest Dervish warriors, swords gleaming and spearpoints glittering in the torchlight.

Gordon met them at the top of the staircase.

They all stood motionless for several moments, until one of the Dervishes cried out, “O cursed one, your time has come!” Gordon is supposed to have said nothing in reply but merely made a dismissive, almost scornful gesture, and began to turn away.

It was then that one of the Arabs threw a spear at him, driving it deep into Gordon’s chest and through his heart.

The General’s body toppled off the stairs and was immediately set upon by the jubilant Ansar, who hacked at it for some minutes until they were sure he was dead.

While this latter version of Gordon’s death was immediately immortalized in the lore of the Empire—and as a display of heroic disdain in the best “stiff upper lip” British tradition, it was inevitable that it would be so—later observers came to believe that the version of Gordon’s death which had him, revolvers in hand, submerged in a sea of hacking, slashing enemies was more likely the way the General had actually met his end.

Certainly it would have fit his character, for someone of Gordon’s personality could only go down fighting.

The idea of Gordon seeking sanctuary in the American consulate is simply impossible to believe given his strong fatalistic streak.

Having many years earlier expressed his belief that he was God’s tool to be used or discarded when and as the Almighty saw fit left no room for such efforts at self-preservation.

If Khartoum fell, Gordon could only believe that his usefulness had ended, and so with it should his life.

And yet, there is an element about the third version, with Gordon standing atop the steps, staring down his would-be assailants, which has a certain ring of truth to it as well.

Most certainly it was an almost stereotypical Victorian demise: the victim, noble but flawed, looking Death squarely in the eye, without the slightest evidence of fear or dismay, showing only disdain for the fate that was about to overtake him.

It was an image that Victorian Britain embraced without question or shame, for it was the portrait of the death of a man who was perceived, with some justification, to personify all that Victorian Britain stood for.

And while there is an element of romanticism in this vignette, there is also an element of validity: Gordon could have died in exactly this manner.

The steely-eyed stance at the top of the stairs, the contemptuous dismissal of his would-be executioners, the sheer theatricality of the entire scene, is one that would have appealed to Gordon, who understood the dramatic gesture better than most of his contemporaries.

Given the sort of man he was, it would have been a fitting death.

Whichever version is true, what happened next is unquestioned.

Gordon’s head was cut off and placed atop a pike, where it was paraded through the Arab camps and then taken before the Mahdi as a trophy.

The body was left to lie in the street, where any passing Ansar was encouraged to jab his spear into it; later, that afternoon, it was thrown into a well.

When the head was brought to the Mahdi, Muhammed Ahmed was horrified.

He had given, he thought, strict orders that Gordon’s life be spared, and had no wish to see his antagonist’s body mutilated.

Whether this decision was made out of a grudging respect for Gordon or because he wished to have the General join his other European captives, as one more living trophy and proof of his invincibility, is unknown.

What is known is that the Mahdi feared that he would be accursed because Gordon’s death had come at the hands of his followers.

The pillage and plunder, rape and murder, lasted the better part of a day.

Exactly how many lives were lost is unknown, although some figures run as high as thirty thousand men, women, and children being either executed out of hand and or sold into slavery, which was hardly the better fate.

Two days later, the steamer

Bordein

chugged up the Nile and came within sight of the city.

Heavy rifle fire and some artillery shells greeted the boat, which was, of course, carrying the advance party of Relief Expedition.

The sheer volume and intensity of the Arabs’ fusillade, along with the absence of any British or Egyptian flag flying from the roof of the Governor’s Palace, convinced those aboard that the worst had happened, the rumors were true.

The city had fallen and Gordon was either dead or a captive of the Mahdi.

In any event, the little force aboard the

Bordein

was far too small to take on the whole of the Mahdi’s army, and recapturing Khartoum was never part of Wolseley’s orders or the instructions he gave Sir Herbert Stewart when the Camel Corps set out from Korti.

Reversing her engines, the

Bordein

made a hasty retreat back down the Nile to Metemma.

In the meantime, on instructions from Wolseley, General Buller had taken two regiments, the Royal Irish Regiment and the West Kents, to Korti, where he assumed command of the Desert Column.

Setting out from Korti on January 29, 1885, his plan was to attack Metemma.

The town itself was still held by the Ansar, and an earlier attack by the Camel Corps had failed, although losses were thankfully light.

Once he arrived on the scene, Buller surveyed Metemma and its defenses, and concluded that it was too strongly held to be taken by the force under his command.

With Khartoum lost, there was no need for the town and its waterfront, which in the original planning had been designated as the staging area for the final push into the Sudanese capital.

In fact there was no longer a need for the Relief Expedition at all, and Buller immediately began pulling his troops back toward Korti.

At the same time, though, the River Column continued to advance.

On February 24, just twenty-six miles below Abu Hamed, with the Nile Cataracts behind them and the passage to Khartoum seemingly open before them, the men of the column, by now all veterans of desert campaigning, heard the news: Khartoum had fallen and Gordon was dead.

The River Column put about, and now began gently drifting down the river up which it had just so laboriously muscled its way.

Upon reaching Cairo in March, the British soldiers would once again board transport ships, this time bound for Afghanistan, where Russia was suddenly threatening war.

Apart from the handful of British soldiers aboard the

Bordein

, the officers and men of the “Gordon Relief Expedition” never came within sight of the city of Khartoum.

The Mahdi’s victory in capturing Khartoum, coupled with the sight of a retreating British army, caused most of the remaining desert tribes of the northern Sudan to flock to his banner.

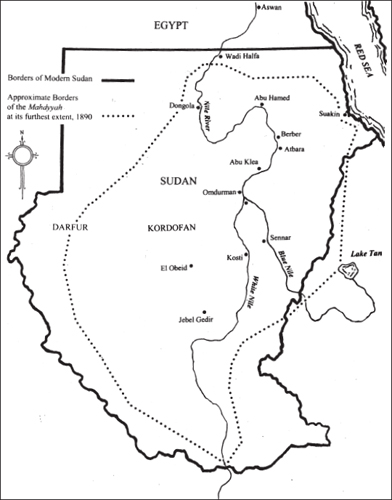

He was now the undisputed master of the whole of the country from Equatoria in the south to the Egyptian border in the north, from the Red Sea in the east to the Saharan wastes in the west.

What he would do next was anyone’s guess, but certainly it could not be expected that he would stop there.

He had threatened to carry his

jihad

into the heart of Islam and the Ottoman Empire, and then turn on Europe: there was no reason to believe that he would not attempt to do just that.

London was worried and Cairo was frightened.

When the news of Khartoum’s fall and Gordon’s death reached Great Britain, the outcry was deafening.

Memorial services were held the length and breadth of the country, as Britons of every class, but particularly the middle and working classes, felt that a symbol of the Empire had been destroyed.

Many felt as though they had lost a personal friend.

Ministers found inspiration for innumerable sermons in Gordon’s “gallant death,” and Queen Victoria, writing to the General’s sister Augusta, gave voice, as she did so many times during her reign, not only to her own sentiments but also those of the nation:

HOW shall I write to you or how shall I attempt to express WHAT I FEEL!

To THINK of your dear, noble, heroic Brother, who served his Country and his Queen so truly, so heroically, with a self-sacrifice so edifying to the World, not having been rescued.

That the promises of support were not fulfilled—which I so frequently and constantly pressed on those who asked him to go—is to me GRIEF INEXPRESSIBLE!

Indeed, it has made me ill…Would you express to your other sisters and your elder Brother my true sympathy, and what I do so keenly feel, the STAIN left upon England, for your dear Brother’s cruel, though heroic, fate!

The British public’s grief was equaled only by its indignation.

Gladstone found himself being booed in public as the British people blamed him and his prevarication for what they saw as a disaster and humiliation for the Empire.

By spring a growing crisis in Afghanistan, where Russian expansionism had been encouraged by what Moscow saw as Great Britain’s preoccupation with Africa, would begin to erode his base of power in the Commons, and by the end of the summer the Conservatives, joined by the Irish Nationalists who had previously been staunch Gladstone allies, would maneuver him out of office.

The “imperial adventure” that Gladstone had never wanted, and into which he had been forced when his attempt at a clever political solution—sending Gordon to Khartoum as a gesture, to give the appearance of “doing something”—fell apart, had played a major part in his fall from office.

In the meantime, both in London and Cairo, government officials waited anxiously for the Mahdi’s next move.

He in fact had only one place to go: down the Nile into Egypt.

THE MAHDYYAH IN 1890

Other books

Baby Brother by Noire, 50 Cent

Mrs. Lee and Mrs. Gray by Dorothy Love

His Captive Bride by Shelly Thacker

Afterglow: An Apocalypse Romance by Monroe, Maria

Wicked While He Watches -The Billionaire's Secret (Claire and the Billionaire) by Nordstrom, Mercedes Eva

Gather My Horses by John D. Nesbitt

Something Wet: Beach House Nights Book 2 by Lyric James

PIGGS - A Novel with Bonus Screenplay by Barrett Jr., Neal

Silent Cravings by E. Blix, Jess Haines