First SEALs (25 page)

Authors: Patrick K. O'Donnell

A photo showing German U-boat pens along the French coast. The Maritime Unit planned a daring combat swimmer operation to disable the pens prior to D-Day.

Various SS officers who ran the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, where Jack Taylor was a prisoner. They committed numerous atrocities, which came to light during the Nuremberg Trials.

A Mauthausen inmate who met his death (one of many) on the electrified barbed wire that surrounded the camp. Mauthausen was the epicenter for a string of labor camps in Austria that could house tens of thousands prisoners at a time. Experts estimate several hundred thousand men, women, and children died in the camps.

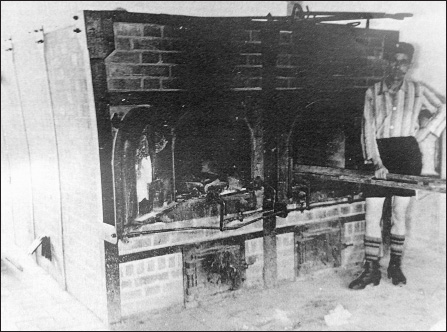

The crematorium at Mauthausen Concentration Camp, where the SS burned the dead bodies of tens of thousands of inmates. Jack Taylor and other inmates were forced at gunpoint by vicious German guards to build the ovens, brick by brick.

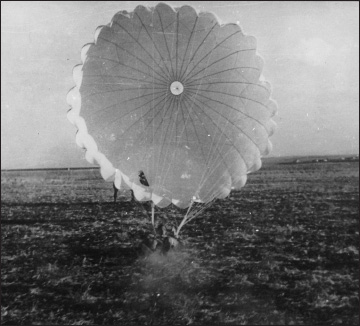

A member of the Maritime Unit receiving Airborne training. Many of the unit's members were parachute-qualified, unlike the Navy's Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs). Maritime Unit operatives, much like modern SEALs, combined special operations with intelligence gathering.

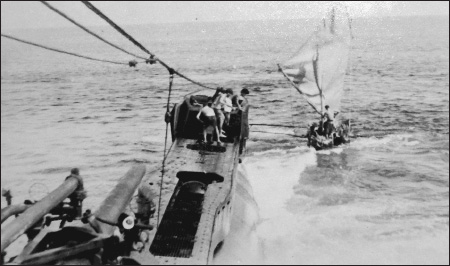

A Maritime Unit submarine-launched operation in the southeast Pacific. Maritime Unit swimmers also conducted critical reconnaissance and demolitions that enabled the Navy to land on key islands in the later stages of World War II.

B

Y THE SUMMER OF

1944

, the Allies had Italy contained and continued the long bloody advance up the mountainous spine of the country. The OSS's focus shifted farther north to the Third Reich itself. The fledgling intelligence agency had successfully utilized many Italian recruits in their campaign to take that country, and now they hoped to do the same in Austria.

The Allies tapped Oxford-educated OSS Major John B. McCulloch, stationed at the base in Bari, to head up the search for Austrians who could be persuaded to support the Allied cause. Wealthy and affable, McCulloch spoke three foreign languages, including German, which served him well in his role as a recruiter. He was particularly good at disguising interrogation as small talk, ferreting out valuable intelligence, and helping to identify prisoners interested in changing sides.

When McCulloch and those who worked with him identified potential recruits, they sent the “Deserter-Volunteers,” or DVs, to a pair of villas in Bari. There the would-be operatives received American GI uniforms and began training, for their new careers as spies. One incident drove home the perilous nature of their new occupations. During training, the parachute belonging to one of the Austrians got tangled up as he was jumping from the plane. He perished, pummeled to death when the wind battered him against the fuselage of the plane.

It was from this group of DVs that McCulloch would select the men for the Dupont Mission, a daring parachute drop into the heart of German-held Austria. It would be OSS's deepest parachute penetration into the Third Reich. The operatives would collect intelligence on the Austrian city of Wiener Neustadt. Located about twenty-five miles south of Vienna, the city was a major transportation hub and key stop on the German supply lines as well as the home of an airplane factory. In addition, the Allies had heard rumors that the Reich was constructing a belt of defensive fortifications known as the Southwest Wall in the region.

Obsessed with being in the heart of the action, Taylor once again left his operations officer's position and volunteered to lead the Dupont Mission into Austria. After spending weeks behind the lines in Albania, surviving an experience that would kill most men, Taylor convinced McCulloch he should lead the mission. It wasn't an easy sell: despite being one of the OSS's most experienced operators, he spoke almost no German. Therefore, it was essential that he have comrades who were not only fluent in the language but also well acquainted with the region and its culture.

The first DV selected to accompany Taylor went by the all-too-Anglified name of Underwood. A sandy-haired, blue-eyed Austrian, he had been drafted into the Reich's Army in the winter of 1942. Coming from an intensely anti-Nazi family, he had one goal: to desert at the first possible opportunity. In January of 1944 he finally saw his chance. Newly assigned to the infantry, he arrived at the Italian front and asked for permission to scout the American lines. With permission granted, he left camp and summarily tossed his weapon into the underbrush. After an hour and a half walk, he arrived at a group of green tents that he knew housed U.S. soldiers. Cautiously, he walked up to one and drew back the flap. The four sleeping GIs inside barely stirred. He crept over to one of the men and gave his blanket a tug. “

I am an Austrian,” Underwood announced in English. “I want to help you.”

The OSS first assigned Underwood to its propaganda section, Morale and Operations (MO). Under their direction he wrote German leaflets full of misinformation. Occasionally he would slip into a German uniform and infiltrate enemy lines. There he would attempt (often successfully) to convince the men that their German officers had ordered them to surrender. But McCulloch snatched up Underwood for the Dupont Mission, offering him the chance to do more serious damage to the Germans.

Underwood felt something bordering on hero-worship for Taylor, who would lead the mission. The taciturn American with a drive to be part of the action seemed an inspirational figure to the younger Austrian, the only deserter-volunteer selected for the mission who spoke English. But Underwood had less fondness for the other two men McCulloch selected for the mission: another Austrian, code-named “Perkins,” and a former member of the

Luftwaffe

, code-named “Grant.” With only a grammar school education that ended when he was fourteen, Perkins, a stonemason, was of a lower social class than Underwood, a distinction that was intensely important in the European society of the time. Underwood's father had been a personal friend of the Austrian chancellor, and he felt that working with both of the other Austrians, Perkins in particular, was beneath him. However, the uncouth Perkins did have some attributes that made him well-suited for Dupont. The dark-haired, stocky twenty-three-year-old had been a paratrooper, a skill that would be valuable on the mission, and he came from the village of Saint Margarethen, which was very close to the drop zone and provided him with invaluable contacts.

The final member of the team, Grant, was from Prague and had Czech ancestry. Grant said he had been a medical student before being conscripted into the German air force, but he later demonstrated a willingness to stretch the truth that led some, including Underwood, to question his story. Underwood disliked the blond-haired, gray-eyed man, but Grant seemed to get along well with most other people. The former officer claimed to have been married and that his

father had been the director of a glass factory. He loved to talk, but he also gained a reputation for severe mood swings. His predilection for womanizing would cause trouble for the team later on.

The team didn't get along well. Due to the language barriers, they couldn't even communicate well. But despite their tensions, they would be forced to cooperate, as they would be virtually alone, deep in the heart of enemy-held territory. For the rest of the summer Taylor and his team prepared for their mission.

Taylor went on a training blitz, learning many of the same sorts of skills that would be necessary for the future SEALs. His first stop: parachute training at the Royal Air Force (RAF) facility located at the Rabat David Airport in Haifa, Palestine. The RAF put Taylor through the pacesâfourteen days of intense training divided into three parts: physical conditioning, synthetic training (tumbling, exits from a grounded plane, including being dragged across the ground in a parachute harness), and, finally, actual parachute jumps. Taylor would make eight practice jumps to become airborne qualified by the Brits. Unlike American paratroopers, who exited the side door of transport planes, Taylor dropped through a hole in the belly of a British bomber, an exercise that foreshadowed Dupont's actual parachute drop into Austria only a few weeks away.

Next Taylor went though Lysander training. Renowned for its ability to land in a fifty-yard field, the Westland Lysander single-engine aircraft was ideal for covert operations. It dropped and picked up Allied agents throughout occupied Europe. Taylor learned how to fly the plane and quickly get in and out of the aircraft. Shortly after Lysander training, he went through Container School, where he learned to pack and parachute-drop the type of containers that would bring Dupont's gear and equipment into Austria.

The final leg of Taylor's training regime in Haifa included a “

refresher course” known as ME-102. Here Taylor practiced with silenced pistols, blew up bridges, and sharpened his skills at sowing mayhem behind German lines. Based on the intense training and his past experience, Jack Taylor felt ready.