Flags of Our Fathers (11 page)

Read Flags of Our Fathers Online

Authors: James Bradley,Ron Powers

Tags: #Biography, #History, #Non-Fiction, #War

Not surprisingly, the military hierarchy had little respect for the products of the system they had designed. They referred to army draftees as

“issen gorin.” “Issen gorin”

meant “one yen, five rin,” the cost of mailing a draft-notice postcard—less than a penny.

“They were expendable; there was an unlimited supply for the price of the postcards. Weapons and horses were treated with solicitous care, but no second-class private was as valuable as an animal. After all, a horse cost real money. Privates were only worth

issen gorin

.”

Later in the Pacific campaign, a captured Japanese officer observed American doctors tending to the broken bodies of wounded Japanese soldiers. He expressed surprise at the resources being expended upon these men, who were too badly injured to fight again. “What would you do with these men?” a Marine officer asked. “We’d give each a grenade,” was his answer. “And if they didn’t use it, we’d cut their jugular vein.”

To the Japanese fighting man, surrender meant humiliation. His family would be dishonored, his name would be stricken from the village rolls, he would cease to exist, and his superiors would kill him if they got their hands on him. All in the name of a version of Bushido cynically devised to make young Japanese men fodder for the military’s adventures.

Unable to surrender, forced to fight to the death, the young Japanese soldier had no respect for Americans who didn’t do the same. So a tragedy occurred in the Pacific. A tragedy brought about by the Japanese military leaders who forced their brutalized young men to be brutal themselves.

Back in America, the dramatic island victory on Guadalcanal and its heroes galvanized a new wave of American boys. The Marines, a volunteer force, had suddenly become the branch of choice, especially among boys who, like Jesse Boatwright, were looking for the biggest challenges: “We felt they sent the Marines to the toughest places, and if it wasn’t tough, the Army went in.”

Young kids were faking birth certificates and urine samples—not to get out, but to get in. Pee Wee Griffiths made it into boot camp by stuffing himself with bananas. At one hundred eight pounds, the Ohio boy was rejected on his first enlistment try; he was four pounds under the Marine minimum. “They told me to eat as many bananas as I could,” Pee Wee recalled to me. “I ate so many bananas, it felt like thousands. But it only put two more pounds on me. But when I told them how many I’d eaten they must have felt sorry for me; they let me in.”

James Buchanan signed with literary visions of war crowding his thoughts. He’d been inspired by the book

Guadalcanal Diary,

published just as he came of age.

And then there was Tex Stanton, a dark-haired boy from the Lone Star State who by rights should not have been a Marine. Tex had a bad right eye. Some young men might have used this as a legitimate excuse to duck service. Tex Stanton found a way around it. Sitting in front of the eye chart during his physical, he managed to hold the “blinder” card in such a way that he could recite the letters twice with his good eye. His impairment was detected during a second physical, but the Texan appealed so strongly that the doctor shrugged and passed him through. He would become an outstanding BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) man, a close buddy of the flagraisers.

“You went into the Marines because you wanted to be the best,” Stanton reminisced to me many years later. “We had the hardest training, hit the hardest spots. We

were

the best.”

Their first stop was basic training: boot camp.

It was the mission of boot camp to quickly convert recruits’ naive boyish fervor into something American society had never generated before: a mass-produced, numerically immense cadre of warrior-specialists at once technically sophisticated and emotionally impervious to the horrors of battle.

And selfless. These masses of kids from a nation of individualists would have to be processed through a radical redefinition of the Self. No longer would a boy be the center of his sunlit universe—family, friends, neighborhood, town, or city. Now his selfhood would consist of integer in a precision-tooled, many-faceted human war machine.

Battles are won by teams working together, not by heroic individuals fighting on their own. The central function of boot camp was to erase the impulses of individuality and get the recruits thinking as members of a team.

Aware that the American individualistic ethic did not lend itself to easy subordination, the military designed basic training as “intensive shock treatment,” rendering the trainee “helplessly insecure in the bewildering newness and complexity of his environment.” Individuals had to be broken to powerlessness in order that their collectivity, their units, might become powerful.

As Jesse Boatwright told me, “The first thing you learn is you’re training for war and you’re not going in alone. War is a team sport. From the general on down, everybody is a team and all of you have to do your part.”

William Hoopes remembered that “they break everybody down as an individual. Our drill instructor (DI) would have us fall out at two-thirty or three

A.M.

He’d say things like, ‘Everybody fall out, I don’t want to hear any fucking noise except your eyeballs clicking.’”

And Robert Lane recalled, “The discipline was extremely tight. You didn’t cough unless you had permission.”

“When you first enter the Corps,” wrote Art Buchwald, “their only goal is to reduce you to a stuttering, blubbering bowl of bread pudding…The purpose…is to break you down, and then rebuild you into the person the Marine Corps wants…”

“It was a subtle destruction of your civilian mentality,” is how Robert Leader remembered it. “And I mean that in a good way. A Marine can’t think like a civilian, he has to think differently to be a good fighter.”

The erasure of individuality would create malleability to discipline; repetitive actions would instill that automatic response for which the services strove.

And there was more. “Don’t get close to anybody,” the tilt-brim, chin-strapped drill instructors would warn boys not long removed from earning their World Brotherhood Boy Scout patches. “Because every other one of you sum’bitches is probably gonna get killed!” When a recruit named Eugene Sledge innocently wondered why his sergeant had asked him about scars or birthmarks, the topkick barked back, “So they can identify you on some Pacific beach after the Japs blast off your dog tags!”

They were growing fit; learning drill and marksmanship and weaponry and chain of command, learning to obey. They were learning to repeat simple, vital tasks ad nauseam; learning to live in alternating states of boredom and lethal urgency.

It was a world in which the basic implement of combat, the rifle, was an object of obsession. The rifle was cleaned several times a day. The rifle was a Marine’s best friend. The rifle had to be taken apart into its thousand parts and then reassembled, on the double. And then taken apart and reassembled blindfolded. The use of the rifle was mastered—standing, sitting, prone—or else. The rifle, sometimes several of them, was a recruit’s bedmate if he screwed up. Above all, the rifle was a

rifle

. Make the dipshit mistake of calling it a “gun” and you got humiliated before the entire company—forced to run up and down in front of your buddies in your skivvies, one hand holding your rifle and the other your gonads, screaming over and over: “This is my rifle and this is my gun! One is for business, the other for fun!”

All militaries harden their recruits, instill the basics, and bend young men to their will. But the Marine Corps provides its members with a secret weapon. It gives them the unique culture of pride that makes the Marines the world’s premier warrior force. “The Navy has its ships, the Air Force has its planes, the Army its detailed doctrine, but ‘culture’—the values and assumptions that shape its members—is all the Marines have.” They call this culture

“esprit de corps.”

“No one can explain esprit de corps,” the veteran Jesse Boatwright told me. “They drilled it into you from the word go. You’re the greatest, they told us. And they showed us why. They showed us the history of the Marine Corps, the proud history. They made you feel like you were a part of a great chain of events.”

For Pee Wee Griffiths, esprit de corps brought him into contact with greatness. “I thought I was special because I had great men among me,” he said, “and I thought maybe some day I could be special like them. You looked up to those guys. That’s what made us feel proud. Great leaders, great men.”

Newsman Jim Lehrer would later write about the special Marine warrior pride ingrained into him in boot camp: “I learned that Marines never leave their dead and wounded behind, officers always eat last, the U.S. Army is chickenshit in combat, the Navy is worse, and the Air Force is barely even on our side.”

And becoming a member of this elite force was not automatic.

In boot camp the boys were cautioned: “You are not Marines. You are recruits. We’ll see if you will be worthy of the title of United States Marine!”

Earning the title of Marine was an honor recruits strove for. As Robert Lane put it, “You thought the Marines were the best and you had to be the best.”

Alone among the U.S. military services, the Marines have bestowed their name on their enlisted ranks. The Army has Army officers and soldiers, the Navy has naval officers and sailors, the Air Force has Air Force officers and airmen—but the Marines have only Marines.

“We felt we were superior to any serviceman,” was how William Hoopes summarized the process. “They made you into the best fighting man in the world.”

Photo Insert 1

Mike Strank—First Communion.

Right: Franklin Sousley.

Below: Franklin Sousley’s birthplace, Hilltop, Kentucky.

Rene Gagnon.

Ira Hayes and his father, Jobe.

Jack Bradley in front of the family home in Appleton, Wisconsin.

Harlon Block and his brothers. From left to right: Mel, Ed, Harlon, Larry, and Corky.

Jack Bradley and family. From left to right: Kathryn (in the back), Mary Ellen, Marge, Jack, Jim, and Cabbage.

Harlon Block in his USMC dress blues.

Ira Hayes in his USMC service uniform.

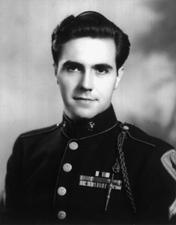

Rene Gagnon in his USMC dress blues.

Jack Bradley in his Navy dress blues.

Franklin Sousley in his USMC dress blues.