Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (23 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

BOOK: Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership

6.23Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The Republicans were outraged by the Sedition Act, and not overly delighted with the rest of the program. Jefferson, an astute political tactician, however woolly he might be about international affairs and the economic future of the country, was a sincere supporter of civil liberties and wrote a series of resistant resolutions adopted by the new state of Kentucky (admitted with Vermont in 1792), while Madison composed resolutions for Virginia. Kentucky claimed a right to nullify federal legislation that violated the constitutional delegation of unallocated powers to the states and citizenry, while Virginia, under Madison’s guidance, only charged states with having to “interpose for arresting the progress of evil.”

Both states repeated their firm adherence to the Union, and softened their resolutions in response to the objections of other states, but for Jefferson to raise the flag of state nullification, on its own authority, of federal laws it judged ultra vires, was opening the door to severe internecine strife. This sequence created an extremely nasty atmosphere, and Adams, who had the advantage with the XYZ affair and backlash against foreign meddlers, must be held responsible for allowing, and in some respects encouraging, the poisoning of the atmosphere, and especially the straight partisan prosecution of Republican editors. Washington would never have sponsored such extreme measures or allowed the atmosphere to become so overheated, though he did publicly support the Alien and Sedition Acts as necessary in the circumstances. (To give the measures some perspective, the British five years before had prescribed transportation to Australia for up to 14 years for any dissent from the war with France. The French Revolution brought down a frenzied atmosphere, particularly in France itself, where any offense, real or imagined, resulted, for a time, in immediate public execution.) The Sedition Act passed the House by only 44 to 41, and was actually milder than the existing seditious libel laws.

Hamilton was still very influential with the Federalists and with Wolcott, Pickering, and McHenry, and he aspired now to be the commander of the new army that was being created. When there was an uprising of German Americans in northeastern Pennsylvania in 1799, Hamilton urged drastic action. Adams sent 500 militiamen, who put the small disobedience down promptly and without casualties. The ringleader, John Fries, was condemned to death, but pardoned by Adams. Hamilton was advocating a new program he had cooked up, including war with France in alliance with Britain, to take over all of what are now the southern and central states of the U.S.; promotion of revolt in Latin America under American leadership by a large army he would command; higher taxes to pay for the large European-sized military establishment and an extensive system of roads and canals to accelerate population growth and economic development; a more extensive court system to regiment the population more closely; and the fragmentation of Virginia and some of the other large states to reduce their importance relative to the federal government (though fragmenting Virginia into three states would have tripled the number of Virginia senators).

61

61

Hamilton, practicing law in New York and well away from Washington’s guidance, had become an authoritarian militarist. Jefferson was backsliding toward an almost confederationist view. Adams held the political center, but without the grasp of the political arts necessary to make it a position of strength. He did move to excise Hamilton’s influence in May and June 1800 by firing McHenry and Pickering, and named the formidable John Marshall secretary of state.

Adams also had moved to cut Hamilton off at the end of the limb by sending a new commission to France, after Talleyrand publicly stated that an American minister would be respectfully received. The new minister, William Vans Murray; the chief justice of the U.S., Oliver Ellsworth (John Jay had retired to become governor of New York, replacing Clinton); and the governor of North Carolina, William Davie (replacing Patrick Henry as a delegation member, who declined because of age and health and died shortly after the others departed in the spring of 1799) were the commissioners and were courteously received in Paris. All the saber-rattling had got the attention of the French, who did not need war with a fierce and rising America at this point, as they contemplated the ancient puzzle of how to suppress their trans-Channel foes, after Admiral Horatio Nelson had defeated the French Navy in the Battle of the Nile in October 1798, deferring indefinitely any possibility of a French invasion of England and stranding Bonaparte in Egypt. Adams was in danger of losing public opinion to Jefferson, but his policy was successful, as a new treaty with France, the Convention of 1800, was signed on September 30, 1800, superseding that of 1778 and ending any defensive alliance while normalizing relations with France.

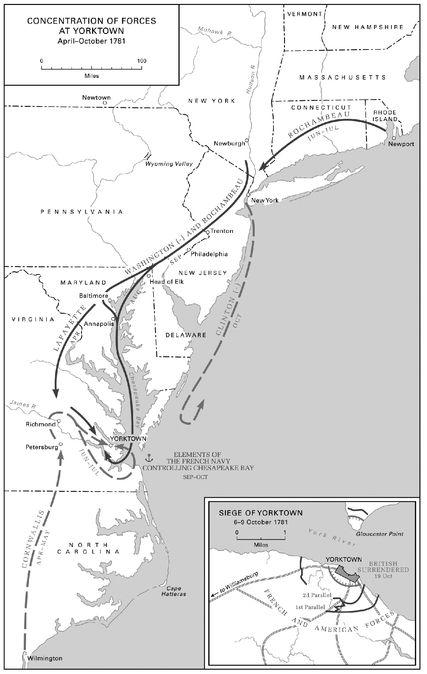

American Revolutionary War. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

George Washington had died just 17 days before the end of the century of which he had been one of the greatest historic figures, an event observed with universal respect. His last view of Mount Vernon, where he peacefully passed away, aged 67, was of his estate covered in snow. In his will he emancipated his slaves and provided financially for their welfare. General “Light Horse” Harry Lee, congressman (and father of General Robert E. Lee), in his moving official eulogy on December 26, 1799, spoke nothing but the truth in describing the late president as “first in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen.” The event caused only the briefest pause in the wild political blood-letting that had so appalled the deceased leader.

After a decade of its new constitutional arrangements, the United States had enjoyed a 70 percent gain in population and a tripling of the national economy, and had gone to the brink of war with first Britain and then France and extracted favorable arrangements with both. Washington had briefly lost public opinion with Jay’s Treaty, and Adams lost many of his partisans with the Convention of 1800 without gaining much from Jefferson, who favored the French treaty but was still agitating the country over the kangaroo courts that convicted 10 of his editors. Adams, ex-diplomat as he was, proved strategically competent but politically vulnerable. Hamilton, who was becoming increasingly irrational, lashed out at Adams with a 54-page letter for the Federalist establishment acidulously assessing Adams’s presidency, published with rejoicing by the Republicans as soon as they got hold of it in the summer of 1800. Hamilton was trying to promote Charles C. Pinckney’s candidacy over Adams but must have known that the inevitable beneficiary would be Jefferson, whom Hamilton now perversely claimed to respect more than Adams.

7. JEFFERSON AS PRESIDENTThe divisions among the Federalists seemed to assure Republican victory in 1800. The main issues were the Alien and Sedition Acts, the increased taxes to pay for the larger military budget, and the revival of anti-British sentiment—while French-American relations started to improve, the British went back to seizing American ships and sailors. These were all negative issues for the Federalists, and the disaffection of Hamilton and his powerful faction redounded to Charles C. Pinckney’s benefit opposite Adams but also helped the Republican candidates, Jefferson and Aaron Burr. The electoral votes came in 73 votes each for Jefferson and Burr, 65 for Adams, 64 for Pinckney, and one vote for John Jay. It could be assumed at first that this would assure Jefferson’s election, but as no distinction was made on the ballots of the division of office between two candidates, it was a tie for the presidential vote, which Burr now professed to have been seeking. There being no majority, the election moved from the Electoral College to the House of Representatives, where the delegation of each state caucused to decide on a candidate and then cast a single vote for that candidate. The Federalists had the majority in the House and preferred the suave and charming but devious and, in policy terms ambiguous, Burr over their ancient foe, Jefferson.

But against this trend, Hamilton was convinced that Burr was a scoundrel and an opportunist, a cunning man of no integrity, and that Jefferson was preferable to Burr, as he was also to Adams, because of what Hamilton professed to consider a betrayal by Adams in seeking reconciliation with France. Hamilton applied his almost demonic energy to supporting Jefferson over Burr, as Adams and Pinckney had distinctly, though narrowly, lost. There were 35 ballots between February and February 17, 1801, without a winner. There was discussion of a statutory declaration of a winner, and the Federalist House could have professed to elect Pinckney or even Hamilton president, though this would have badly snarled the process and opened it to challenge before the Supreme Court. Jefferson warned the governor of Virginia, his protégé James Monroe, that Virginia should be ready for armed resistance should any such effort be mounted.

62

62

The Federalist senator from Delaware, James Bayard, received from a Maryland Republican, General Samuel Smith, what he professed to consider assurances from Jefferson that he would preserve the Hamilton financial program and Adams’s new navy and would only dismiss Federalist officeholders for cause. It was later denied that any such promises had come from Jefferson, but believing they had that comfort level, the Federalists arranged votes and abstentions within state congressional delegations that tilted the vote on the 36th ballot: 10 states for Jefferson to 4 for Burr, and 2 states unable to declare a choice. (Tennessee had become the 16th state in 1796.) The Jefferson Revolution had begun, and this opened the great, six-term reign of the Jefferson-Virginian Republicans. But it began narrowly and uncertainly. Jefferson and Madison had hinted at nullification of federal legislation, in Jefferson’s case on behalf of Kentucky, on the determination of the state alone; and in the electoral controversy, Jefferson and Monroe had corresponded on the possibility of an armed Virginian resistance to a Federalist, legislated election victor, not necessarily an unconstitutional solution. These were profound fissures in the constitutional beliefs of the main political groups, and that is without considering the implications of the smoldering issue of slavery.

In one of his last and most important presidential acts, Adams appointed the very able lawyer and secretary of state, anti-Jeffersonian Virginian John Marshall, as chief justice of the United States, a post he would distinguishedly occupy for 34 years. John Adams, a competent statesman and man of inflexible integrity and patriotism, retired to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, angry and disappointed, but having rendered conspicuous service, and generally respected if not afloat on waves of public affection. He would prove to be the first of four generations of his family of eminent, public-spirited Americans, and the longest-lived of any president of the U.S. until the twenty-first century.

Jefferson’s inaugural address foresaw the steady growth in the power, extent, and prosperity of the nation. He had been an advocate of a small federal government, and thought the Articles of Confederation could have been amended to make an adequate framework, and that the presidency, as created, was an elected monarchy, “a bad edition of a Polish king.”

63

Jefferson immediately set an informal tone to proceedings, dressed casually, delivered messages in writing, and received anyone who wanted to see him, simply, often in slippers, and in the order they appeared, very congenially. He sold Adams’s elaborate coach and horses and traveled in a one-horse market-cart.

63

Jefferson immediately set an informal tone to proceedings, dressed casually, delivered messages in writing, and received anyone who wanted to see him, simply, often in slippers, and in the order they appeared, very congenially. He sold Adams’s elaborate coach and horses and traveled in a one-horse market-cart.

Whether the Federalists thought they had an understanding with Jefferson or not, he did shrink the army drastically, and with the very capable expatriate Swiss banker Albert Gallatin (who had been discommoded by the xenophobia of 1798) as Treasury secretary, vacated tax fields, reduced spending, and reduced debt steadily through his presidency, even as the country continued to grow rapidly. He considered his administration to be Whig against the Federalist Tories, and he mastered the appearances of popular government. He considered the Bonapartist coup seizing power for the new consulate to be confirmation of his aversion to large standing armies, and had never seen any need for such a force anyway. He established the U.S. Military Academy at West Point to train Republican officers to replace the Washington-Adams military establishment, but ultimately to assure a non-political officer corps, a valuable and needed reform. Jefferson did allow himself to be persuaded by Gallatin of the merits of the Bank of the United States, and their various frugalities, especially reductions in the army and navy, helped cut the federal debt from $83 million to $57 million in eight years, despite a nearly 40 percent increase in the country’s population, to about seven million.

Jefferson continued a nationalist tradition in the defense of the nation’s interests in the world and its continued western expansion. Following the example of the British, the United States under its first two presidents had fallen into the habit of paying tribute to the Barbary pirates along the North African coast from Morocco east to what is now Libya. The Pasha of Tripoli (forerunner to Colonel Qaddaffi) increased his extortions for each ship and purported to declare war on the United States on May 14, 1801. Jefferson was less hostile to the navy than to the army, as it was less adaptable for use in domestic repression, and he dispatched a “Mediterranean squadron” that, led in the principal action by Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, destroyed the Pasha’s principal vessel, the former USS

Philadelphia.

A blockade was imposed on the main pirate harbors, and the Pasha eventually thought better of it and signed a peace in June 1805. (Tribute, in reduced amounts, continued to be paid until 1816.)

64

Philadelphia.

A blockade was imposed on the main pirate harbors, and the Pasha eventually thought better of it and signed a peace in June 1805. (Tribute, in reduced amounts, continued to be paid until 1816.)

64

Other books

Prisoner of Earthside: A Novella (STRYDER'S HORIZON Book 2) by Daniel J. Kirk

The Stranger Came by Frederic Lindsay

A Broken Land by Jack Ludlow

Deep Surrendering: Episode Six by Chelsea M. Cameron

Determined: To Love: (Part 2 of the Determined Trilogy) by Elizabeth Brown

Postcards From the Edge by Carrie Fisher

Servants of the Map by Andrea Barrett

The Day I Killed James by Catherine Ryan Hyde

Small Town Secrets (Some Very English Murders Book 2) by Issy Brooke

The Haystack by Jack Lasenby