Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (71 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

BOOK: Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership

9.26Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Hitler took the unusual step of addressing the Reichstag, with Goering, in his capacity as its president, sitting behind him lolling in laughter in his chair while Hitler recited all 31 places of interest in a mocking tone and then gave an acidulous response that “You, Mr. Roosevelt, may think that your interventions will succeed everywhere”; he continued with a self-conscious description of the contrast between mighty America and cramped Germany and of his own success compared with what he implied was the lethargy of the Roosevelt administration, which had come to office just a month after Hitler. The German government had extorted assurances from most of the countries Roosevelt referred to that they had not felt threatened, and he essentially told Roosevelt to stay out of European affairs. As Roosevelt suspected might happen, while Hitler enjoyed himself and amused his countrymen, Americans were offended at seeing their president held up to ridicule for posing what most Americans considered a reasonable question.

The slide toward war accelerated now. Britain’s King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited Canada and the United States in May and June 1939, and made a very good impression. They had been coming to Canada, and Roosevelt invited them to visit the U.S. also as a goodwill and relationship-building gesture, as he had given up on Chamberlain. The American public found the royal couple attractive and unpretentious, and Roosevelt, who had known this king’s father and brother (George V and Edward VIII), found them intelligent, conscientious, and unaffected. Like most people, they were impressed by Roosevelt’s overpowering personality and his evident mastery of American public affairs and opinion, as well as his familiarity with the complicated European arena. The trip was a huge success. Roosevelt drove them to the royal train at the little Hyde Park railway station near his Hudson River home. Large crowds on both sides of the river sang “Auld Lang Syne,” and Roosevelt called out “All the luck in the world.” Ten weeks later, Britain was at war.

The Anglo-Russian negotiations proceeded desultorily, while Hitler sent the Wilhelmstrasse’s crack diplomatic negotiators secretly to Moscow. Roosevelt was cruising in northern waters on the USS

Philadelphia

, in late August 1939. He was in the habit, when he wished to take a holiday, of requisitioning a heavy cruiser and purporting to visit defense installations while in fact fishing and playing cards with his cronies (and waiving, for his party and himself, the rule he had brought in when assistant secretary of the navy in World War I against alcohol on the ships). He received an alert that the German foreign minister, Ribbentrop, was about to go to Moscow, and Hull requested his immediate return to Washington. Roosevelt sent a message to Stalin at once, warning him that if he made an arrangement with Hitler, Hitler might overwhelm France and would then turn on Russia. The Russo-German pact, which included public clauses of reciprocal non-aggression and neutrality in the event of attacks by third parties, and a private agreement on the partition of Poland between them, should Germany attack that country, was signed on August 23. The effect was electrifying, considering the long and acrimonious hostility between the two regimes and Hitler’s pose as a bulwark against both Bolshevism and the Asiatic hordes of central and eastern Russia. (An amiable Stalin told von Ribbentrop: “Your Fuehrer and I have poured pails of dung over each other’s heads but I want you to know I think he’s a hell of a fellow.”)

Philadelphia

, in late August 1939. He was in the habit, when he wished to take a holiday, of requisitioning a heavy cruiser and purporting to visit defense installations while in fact fishing and playing cards with his cronies (and waiving, for his party and himself, the rule he had brought in when assistant secretary of the navy in World War I against alcohol on the ships). He received an alert that the German foreign minister, Ribbentrop, was about to go to Moscow, and Hull requested his immediate return to Washington. Roosevelt sent a message to Stalin at once, warning him that if he made an arrangement with Hitler, Hitler might overwhelm France and would then turn on Russia. The Russo-German pact, which included public clauses of reciprocal non-aggression and neutrality in the event of attacks by third parties, and a private agreement on the partition of Poland between them, should Germany attack that country, was signed on August 23. The effect was electrifying, considering the long and acrimonious hostility between the two regimes and Hitler’s pose as a bulwark against both Bolshevism and the Asiatic hordes of central and eastern Russia. (An amiable Stalin told von Ribbentrop: “Your Fuehrer and I have poured pails of dung over each other’s heads but I want you to know I think he’s a hell of a fellow.”)

Roosevelt sent the customary message to the parties proposing conciliation, under no illusions about the effect of it. Germany invaded Poland in overwhelming strength on September 1. Britain and France declared war on Germany on September 3, the Soviet Union invaded Poland on September 17, Warsaw fell to the Germans on September 27, the country was partitioned between the invading powers on September 28, and the last organized Polish resistance was crushed on October 5. It was a swift and horrifying demonstration of German military efficiency, with heavy use of armored (tank) divisions and heavy tactical aerial bombing, including the indiscriminate bombing of residential areas. Roosevelt declared American neutrality but did not ask Americans to be “neutral in thought,” as Wilson had in 1914. He spoke to the Congress and called for avoidance of any reference to “a peace-party—we are all part of it,” but he called for repeal of the Neutrality Acts in order to permit military sales to the Allies, and this was accomplished on November 4.

On October 11, Professor Albert Einstein (with whom Roosevelt always spoke in German) informed him of the possible development of an atomic bomb and Roosevelt began to take the project directly into the War Department. On October 14, the Soviet Union attacked Finland, but suffered a bloody nose for several months before overwhelming Russian forces finally forced the cession of a Finnish province. The British and the French considered sending forces to assist the Finns, and were preparing to do so when the Finns were forced to negotiate. Entering into combat with the Soviet Union would have been an unimaginable catastrophe for the Allies. Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden had been recalled to government by Chamberlain, Churchill in charge of the navy, the position he had held at the start of the World War I. And Roosevelt, relieved to have a warrior in a position of influence in the British government, initiated direct correspondence with Churchill, as he found Chamberlain hopeless and antagonistic. Hitler made a peace offering, proposing that the combatants end the war with exactly what they now possessed, no concessions by Germany, Britain, or France. Even Chamberlain was no longer interested, having been so bitterly disillusioned by Hitler’s bad faith and barbarity.

Roosevelt sent Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, for whose talents (unlike Hull’s) he had considerable regard, on a mission to Rome, Berlin, Paris, and London in February and March 1940, to see if there were any prospects for peace. He found Mussolini full of bluster, Hitler disingenuously professing preparedness to make peace or war, the French sullen and demoralized, and the British grimly determined, but with no idea of how to win a war, and no prospects of an early peace. Roosevelt had long been convinced that Hitler was a compulsive warmonger who was determined to provoke war, and he doubted that Britain and France, without Russia, could contain Germany as they had, by the narrowest margin, until Russia collapsed, in World War I. In these circumstances, there is little likelihood and no evidence that Roosevelt had any intention of retiring after two terms, as his distinguished predecessors had done. He had written that France could not tolerate remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936, and that Germany would soon be stronger than France. He had warned Stalin about facilitating Germany’s initiation of war, and he had no confidence in the ability of Chamberlain or any French leader in sight to wage war successfully against such a satanic war leader as Hitler at the head of such a military machine as he had built. He doubted the ability of any discernible coalition to defeat Germany without the eventual participation of the United States.

7. THE GERMAN BLITZKRIEG, WINSTON CHURCHILL, AND THE FALL OF FRANCERoosevelt was considering these facts and how, if he were to seek a third term, he would engineer it without scandalizing American concerns about too long an incumbency, when Hitler seized Denmark and invaded Norway, in April 1940. An Anglo-French expeditionary force landed in Norway in mid-April but was forced to evacuate after 10 days. The British would return to Narvik at the end of May, but would again be forced to withdraw 10 days later. It was another snappy, professional German military operation, and it precipitated a confidence debate in the British House of Commons that revealed too many defections from Chamberlain’s Conservative Party for him to continue. Though the foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, was considered for the succession, he was tainted by appeasement and did not feel he could govern from the unelected House of Lords. Winston Churchill was the obvious choice, and on May 10, 1940, King George VI invested him with practically unlimited power as head of an all-party national unity government, in what, with the invasion of the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France that morning, was now an unlimited emergency.

The German campaign plan, called “Sickle-sweep,” devised chiefly by Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, but with Hitler’s personal collaboration, was brilliantly conceived and executed. The Germans struck through what had been thought to be the impassable Ardennes Forest with swift-moving mechanized units, and wheeled right, opposite to the World War I Schlieffen Plan, and drove to the sea, completely separating the British, Belgians, and northern French armies from the main French army around Paris and along the Rhine, in the heavily fortified and underground Maginot Line. The Belgians capitulated on May 28, and 338,000 British and French soldiers were evacuated by hundreds of craft of all kinds between May 28 and June 4, from Dunkirk across the English Channel, as the retreating armies tenaciously defended the perimeter and the Royal Navy and Air Force retained air and sea superiority in the Channel. They left their equipment behind, and Roosevelt immediately (and without consultation in the midst of the intense run-up to presidential elections) sent Britain a full shipment of rifles and machine guns and munitions to rearm the evacuated forces and enable them to defend the home islands if necessary.

104

104

The German army outnumbered and outgunned the remaining French by more than two to one and on June 5 launched a general offensive southward to sweep France out of the war. Italy declared war on France and Britain on June 10, an event that Roosevelt described as striking “a dagger into the back of its neighbor.” Churchill and the French premier, Paul Reynaud, made increasingly urgent appeals to Roosevelt to announce that the U.S. would enter the war (which Churchill knew, certainly, to be completely out of the question), as Reynaud was now wrestling with a defeatist faction that wished peace at any price. His government evacuated to Bordeaux, and Paris, declared an open city, was occupied by the German army on June 14. The 84-year-old Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain, the hero of Verdun, succeeded Reynaud as premier on June 17 and asked for German peace terms.

France surrendered in Marshal Foch’s railway car where the 1918 Armistice was signed, at Compiègne, on June 22. The long battle between the French and the Germans was apparently over, in Germany’s favor, as it crushed and humiliated and disarmed France and occupied more than half the country, including Paris. The Third Republic, which had presided over the greatest cultural flowering in French history and had seen the country victoriously through the agony of the World War I, ignominiously voted itself out of existence at the Vichy casino on July 10, 1940. The fascist sympathizer Pierre Laval would govern in the German interest in the unoccupied zone, in the name of the senescent marshal. Virtually all France, initially, knelt in submission before the Teutonic conquerors, as they marched in perfect precision down the main boulevards of all occupied cities, resplendent in their shiny boots, full breeches, shortish, tight-waisted tunics, and coal-scuttle helmets. Not since Napoleon crushed Prussia in 1806 had one Great European Power so swiftly and overwhelmingly defeated another. And in this case, the occupier intended to stay, and most of France was annexed to Germany, including Paris. Appearances were deceiving, however.

A pioneering advocate of mechanized and air warfare and junior minister in the Reynaud government, General Charles de Gaulle, with practically no support, and representing only the vestiges of France’s national spirit and interests, flew to England on June 18, and declared by radio to his countrymen: “France has lost a battle; France has not lost the war.” He announced the formation of the Free French movement, which would continue the war. As Churchill said, he carried “with him, in his little aircraft, the honour of France.” The major players of the greatest drama in modern history were all in place: Stalin, Hitler, Roosevelt, Churchill, and now de Gaulle.

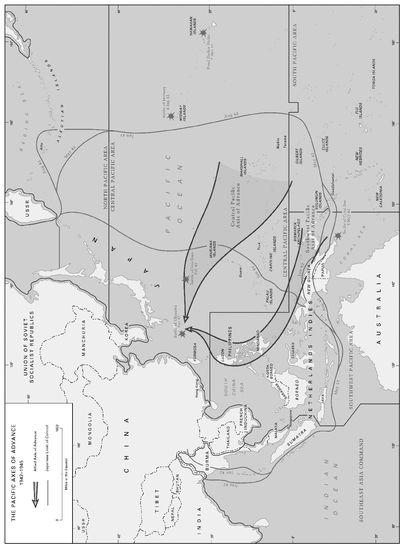

WWII Pacific. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

As the tide of war swept over Europe, Roosevelt kept requesting and receiving increased allocations for military preparedness. As the war began, he installed General George C. Marshall, over many senior officers, to be chief of staff of the United States Army. Marshall urged Roosevelt to mobilize opinion for an increased defense budget and he assured the general that Hitler would take care of that. This was what happened, as Roosevelt ordered eight battleships, 24 aircraft carriers (there were only 24 afloat in the world, almost all in the British, Japanese, and U.S. navies), and an annual aircraft production of 50,000 (five times German production). The remaining workfare programs were entirely given over to defense production. It was the strategic coup of completing victory in one arena (elimination of unemployment) by focusing on the next target (arming America until it was an incomparable military superpower). Unemployment declined by 500,000 per month for the balance of the year and into 1941; that battle was over and won at last. Among the workfare projects were the two soon-to-be historic aircraft carriers,

Enterprise

and

Yorktown

. Unemployment had vanished completely, even in the relief programs, by the autumn of 1941.

Enterprise

and

Yorktown

. Unemployment had vanished completely, even in the relief programs, by the autumn of 1941.

Other books

A Christmas Seduction by Van Dyken, Rachel, Vayden, Kristin, Millard, Nadine

The Accident by Chris Pavone

3 Inspector Hobbes and the Gold Diggers by Wilkie Martin

Murder on the House: A Haunted Home Renovation Mystery (Haunted Home Repair Mystery) by Blackwell, Juliet

Betrothal (Time Enough To Love) by Jaxon, Jenna

Demon Bound by Meljean Brook

Silencio sepulcral by Arnaldur Indridason

The Deeper Game (Taken Hostage by Hunky Bank Robbers Book 3) by Annika Martin

Icon by Genevieve Valentine

Nickel-Bred by Patricia Gilkerson