Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (23 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

Puberty, the physical transformation from girl to adult, takes about four years altogether. It’s made up of three consecutive stages, each one often the source of great pride, distress, confusion, or all three: breast budding, growth of pubic hair, and, finally, menarche. Back in 1830, the average age for a girl’s first blood was seventeen. Today, however, the average age is between 12.8 and 13.2 years, although anywhere be-tween nine and seventeen is considered normal.

What exactly triggers menarche is still hotly debated. Some think it’s brought on by a certain accumulation of fat; others point to skeletal growth. Whatever the precise cause, it’s widely believed that improved nutrition and environmental conditions over the years are what gradually brought the age of menarche down to where it is today.

Ironically, early menarche puts women at a higher risk for cancer, particularly breast cancer, since it exposes the girl to extra estrogen in her lifetime. And creepily enough, there are now ominous signs that the earliest sign of puberty, breast budding, is occurring at younger and younger ages, perhaps due to the so-called obesity epidemic, hormones in our diet, the presence of environmental pollutants, or any combination of the three. Whether or not this affects the age of menarche or a girl’s overall health is still completely unknown.

Early pregnancy fears aside, menarche isn’t necessarily a sign of immediate fertility; in fact, it can take a couple of years not only for a regular cycle to establish itself but also for ovulation to rev up. That being said, menarche has been widely used in many if not most cultures as the sign that a girl is ready to hit the marriage market, and that motherhood, her basic reason for even existing in the first place, is pretty much nigh at hand.

From that day on, my mother was watching over me like a hawk, and often, whenever there was talk about a boy, or she would see me with a boy, she would say something like “don’t get pregnant” or “you know that you can get pregnant now.”

—Cassandra P. (51)

As a result, menarche has also routinely kicked off the time of training the hapless girl so she could handle the responsibilities that would soon be piled upon her slim shoulders. Whether it was a Native American girl drafted into puberty rites, a frontier adolescent learning how to bake bread, or a debutante-to-be being strapped into her first corset, menarche has traditionally marked the definitive end of girlhood, and the start of some heavy expectations.

Twenty-first-century Americans tend to gloss over the event, skittering around any personally meaningful acknowledgment of the physical and emotional changes going on and instead handing off the hapless girl into the waiting arms of the commercial femcare industry. That’s the downer part. The positive part is that there’s vastly more information available to the confused adolescent than ever before, and it’s easily accessible online and in girls’ magazines, too: not only the basic anatomical facts, but even practical tips on how to insert a tampon for the first time and deal with cramps.

Of course, much if not all of that information is provided by the femcare manufacturers, and as saintly and altruistic as some of them may be as individuals, they in fact all share a not-so-secret common agenda, which is to sell their stash. After all, we gals tend to be brand loyalists, especially when it comes to our tampon and pad choices. If a company can successfully woo a preteen, it also gains a potential lifelong customer. As a result, young girls barely beyond Barbie are routinely bombarded with femcare ads, articles, and advice in teen magazines and on the Internet.

So is this really so awful? We sure as hell don’t know. All we do know is that there’s often a highly convoluted dance in teen magazines, in both their articles and advertisements, between good information and constructive tips, and prudish, even repressive advice. Sexy outfits modeled by apparent jailbait will nestle up against articles warning girls “not to go too far.”

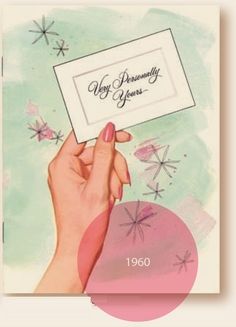

E-cards, Procter & Gamble Company

The same thing holds true for teen magazines and their take on menstruation. A perfectly sensible letter about whether it’s possible to get pregnant during one’s period will be answered in reasonable detail, but it will then be followed by a short story detailing the lurid downfall of a girl who foolishly “let” her boyfriend “go all the way.” This will then be followed by a bouncy, full-page ad extolling the undetectability of a new pad or the flowery scent of a new tampon.

Much of the weird tension between actual information and prudishness and shame in teen magazines and femcare Web sites arises from the complex history of menstrual education. Throughout most of history, it was a mother’s job to teach her daughters about menstruation … or at least, that was the way it was supposed to work in theory. In fact, many if not most mothers shied away from that delicate task and as a result, even in recent years, countless girls have experienced their first period with no real understanding of what was going on and were understandably scared to death to discover reddish-brown sludge in their knickers.

For centuries, menstrual ignorance ran rampant, unchecked by science, facts, or even shared information. And so it was a truly enlightened move back in the nineteenth century, when the first intrepid educators squared their jaws and resolutely set about informing girls about menstruation and fertility. Of course, getting down to the actual factstooka certain amount of revving up:

And now, my dear reader, if you never knew before, you must by this time understand what is meant by being “born.”

You now know that the dear little babies that come to our homes are not brought there by angels, or by storks, or by doctors.

They are not found in the woods, or in hollow stumps, or in birds’ nests, or in hay-mows.

—CONFIDENTIAL TALKS WITH YOUNG WOMEN (1898)

Such books were meant as handy tools to give tongue-tied mothers an easy way to start those gentle, womanly conversations, with the facts conveniently at their soft, white fingertips. As a result, early educators didn’t start off their books with graphic descriptions of menstruation or reproduction; no sir, they began where any gentleman would, which is with the fertilization of plants. The theory was that by discussing acorns, apple trees, and marigolds and then nonchalantly working their way up through the animal kingdom, they could maybe slip human intercourse in there along the way without anyone being unduly alarmed.

I was thirteen, in eighth grade. I knew about it ahead of time, but it was so conceptual to me that when it finally came, I thought I was bleeding to death. I sat down in the washroom (I was at home with my parents and siblings) and saw that I was gushing blood. I didn’t immediately think“menstruation” but rather, “I’m dying!” So I screamed out from the washroom to my parents downstairs, “Call an ambulance—I’m bleeding!”and I could hear peals of laughter in response, which further contributed to my confusion and growing panic.

—Kate R. (47)

Back then, the not-so-hidden agenda woven throughout nearly all of these early so-called educational books was basically how menstruation tied in with a girl’s expected role as future wife and mother. Menstruation, marriage, motherhood: throughout most of history, these were the three Ms that pretty much summed up the lucky girl’s future.

And lest any girl dare to actually dream of becoming something other than wife and mother, McGee Williams and Kane, in On Becoming a Woman, were there to gently, kindly bitch-slap her back into reality, citing her monthly blood: “What do the changes indicate? You’re a girl and you are getting ready for the special role of childbearing. Like every other woman in the world, this is what your body was planned . for. You may think you were intended to be a Hollywood star, or a scientist, or a great writer. But your body ignores all this … . In childbirth, a woman … is creative in a very real sense because she helps create and nourish human beings … . When you know the happiness of childbirth—you will be acting the role you were created for.”

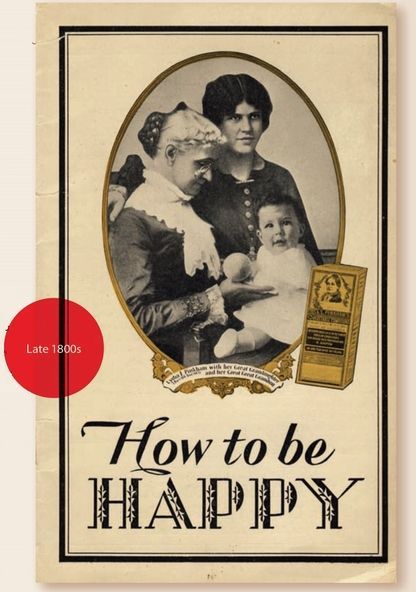

Lydia E. Pinkham Medicine Company

Despite these baby steps in education, there was never a word in any of these early publications about what to actually do with all that menstrual flow! Chapters on hygiene generally went on and on about perspiration (bad), the right way to draw a bath (good, as long as the water was not too hot and certainly never too cold), as well as the pros and cons of whether or not it was okay to wash one’s hair (mixed to bad). But before commercial products were commonly available, there was nary a word written on rag wrapping, packing, pinning, or washing, leaving girls at a relative loss as to what to do.

All this changed when the burgeoning femcare industry realized that in order to survive, it had better get into the menstrual education business, as well, and posthaste. It was only a matter of time until manufacturers realized that they could in fact toss their marketing net even wider—and take aim at not just the menstruators, but the prepubertal set. What better way to build brand loy-altythan by helping mothers help their daughters? How cozy was that?

My mother showed me these pamphlets, “Growing Up and Liking It” and “What Every Girl Should Know.” They each had these cutaway side views of the female reproductive system. I thought getting your period meant having to cut off one leg. Then she took me to a Disney film from Girl Scout group that showed what menstruation was. None of it made any sense.

—Elizabeth O. (52)

Manufacturers started cranking out booklets like “How Shall I Tell My Daughter?” and “Marjorie May’s Twelfth Birthday,” designed to help mothers talk to their daughters by providing information about menstruation and puberty in one easy-to-read place. The booklets oozed not only empathetic support for the brave mother, but also plenty of hard-sell information about their products. In fact, these booklets were little more than advertising wrapped in high-minded education: an early-twentieth-century version of the infomercial.

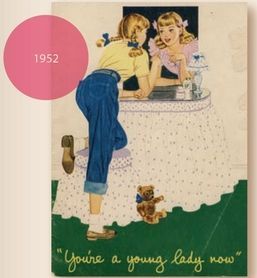

Kotex, Kimberly-Clark

Tampax, Procter & Gamble Company