Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (3 page)

Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

Language illustrates a basic tension: that people may talk about menstruation, but only when they reduce it somehow, dismissing it as the disgusting, eye-rolling nuisance everyone agrees it is. Periods are thus perceived as a dreary thing that happens to us—and not a complex and active process that is actually an integral part of our breathing, sweating, digesting, thinking bodies.

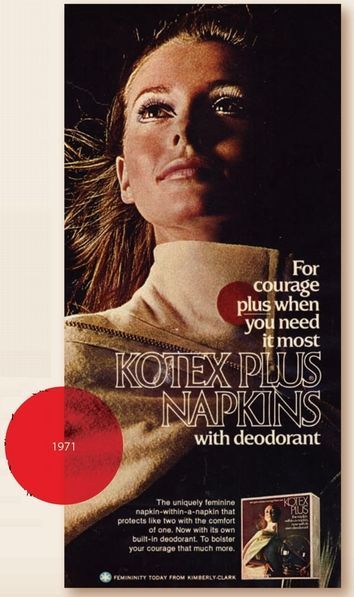

Kotex, Kimberly-Clark

The underlying problem is something that the canny French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir put her nicotine-stained finger on in her groundbreaking 1949 book, The Second Sex: that in a world pretty much defined and dominated by men, women are seen as nothing more than the “other” sex, existing relative to the guys. Therefore, we stare with dismay at our own bodies, the way a landscaper might when faced with an especially unpromising patch of weedy, rocky, lumpy ground that must be ruthlessly weed-whacked into shape. Ever critical of the nagging unpredictabilities of our bodies, we’re beset by anxiety, knowing we’re supposed to be clean, dainty, and in control—and periods (All that blood and bloating! Those cramps! Such a temper!) are anything but.

So how does language fit into all of this?

In every conversation we have, the words we use to describe our bodies and their processes not only reflect but actually reinforce how we feel about them and how other people perceive them. This is why certain spokespeople get to go on the lecture circuit and make tons of dough talking about the power of positive talk … because it’s actually true. The same is true for negative language. If, say, you decide to introduce a new proposal at the office with, “Here’s another bad idea you’re gonna think really sucks,” chances are pretty good you’ve already shot yourself in the foot.

What makes all of this especially sinister is when we suddenly realize (like in our favorite scary story when the babysitter realizes the killer is actually calling from upstairs!) that the words we use, along with all their associations, have been already chosen for us years ago, in some cases even centuries ago. And by not questioning the words we’ve been programmed to use, we have indirectly absorbed their witchy power.

Consider the word “hysteria.” A rampantly popular diagnosis for centuries, it comes from the Greek word hystera, or “uterus.” The ancient Greek doctor Hippocrates (ca. 460 B.C. to 370 B.C.), normally such a swift guy that he was known as the father of medicine, seriously believed that the hystera was wont to wander around a woman’s body. We’re not kidding; he thought the uterus literally liked to mosey around a woman’s torso, into her chest, and sometimes right up into her throat, in its never-ending search for children. Those ramblin’ ways allegedly caused hysteria, a supposed illness that was still being diagnosed in women up until the early twentieth century.

In terms of language, there were no separate words for female genitalia for thousands of years. That was mostly because women were considered pretty much the same as men, only of course flimsier, more poorly designed, and incapable of writing in the snow. As a result, people used the same words to describe male and female organs: the ovaries were considered the female testicles, the vagina a penis, and so on. So how did anyone talk about menstruation, you might wonder? The answer: rarely, and in the vaguest possible terms.

Even today, advertisers and manufacturers tiptoe around the actual words, which are presumably too scary and horrible for our ladylike ears. Commercial menstrual products are commonly referred to as feminine “protection”; but this begs the question, protection against what? Against our big, mean uteruses and those psychokiller ovaries? Not to put too fine a point on it, but would you ever call a tissue “nose protection”?

Even the expression “feminine hygiene” implies that menstruation is fundamentally dirty, yecchy, bad, as does the expression “sanitary pad.” Depending on your taste, menstrual flow may not be the most aesthetically bewitching substance you’ll ever hold in your hand, but it’s certainly not inherently unsanitary, either. Yet advertising, by continuing to refer to menstruation in such unrelentingly negative terms, reinforces the same message, over and over: that our monthly flow is a disgusting problem, a hygienic Three Mile Island, something so scary and awful that it definitely needs a solution. And don’t worry, little lady: like a Fortune 500 knight in shining armor, guess who’s volunteering to come rescue us from all that blood, that mess, our bodies?

In fact, menstruation isn’t a Thing that just happens to poor, passive, slobby ol’ us a few days every month for a few decades. It’s actually a complex event, so much so that doctors and scientists don’t even fully understand it yet or what exactly it does. While it’s true that most of us picked up the uterus-preparing-for-a-baby part by fifth grade, what we still don’t know could fill a medical library. Only a few animal species on earth actually menstruate, humans among them. Why is that? How exactly is monthly bleeding tied to our health?

A big part of the problem is that, overwhelmingly, studies on menstruation tend to be funded by the “femcare” industry itself, and only, of course, to better develop and market their products. (As a rule of thumb, if you ever wonder about a particularly upbeat study plugging a product, just follow the money, honey! You’ll find that, routinely, experts and pundits are quietly on the payroll of the companies whose products they’re so enthusiastically endorsing.)

There have been more objective, scientific studies conducted over the years, but by and large, they tend to focus almost exclusively on the so-called pathological expressions of menstruation—not just the familiar downers like fibroids, endometriosis, and Lizzie Borden-esque PMS, but genuinely bizarro stuff (like the way women living together seem to bleed together, or when menstrual blood actually comes out of your nose).

Not to sound paranoid or anything, but we can’t help but note that very few, if any, science foundations, universities, and places of higher learning frankly give a rat’s ass about healthy menstruation. The U.S. gov ernment itself created the Nationa Institutes of Health’s Office of Women’s Health in 1990, and for a while, their single most burning question about menstruation was, “Does it make women unfit for combat?”

So where does that leave us? Totally in the dark? Screwed again?

Well, we do know some things, for certain. We know that for nearly all women, menstruation is a normal, if wildly variable and profoundly subjective, life experience. Another thing we know is that it seems to involve not just our uteruses, ovaries, and vaginas, but much of the rest of our bodies, as well: our brains, glands, hearts, and other organs. What’s more, no matter how old we are, if we’re female, we’re actually menstrual our entire lives: either pre-, menstrual, peri-, menopausal, or post-. And the stages of our lives are in a sense defined by where we are on the menstrual time line.

Okay, we hear you demur. But why talk about it? We can envision certain relatives, friends, and colleagues pursing their lips en masse and rolling their eyes heavenward. “So this is what you want to talk about? With so much going on in the world, so many things to discuss, this is really so important?”

To which we reply: absolutely.

Recent studies show that up to 10 percent of girls still get their first period without any clue whatsoever as to what’s going on (shower scene from Carrie, anyone?). What’s more, college women consistently exhibit an amazing level of ignorance about the underlying biology of menstruation.

It’s downright bizarre that what’s called “discussion” about this most complex yet universal of processes has become one almost completely moderated by business and medicine. We’ve been taught our talking points by people who are frankly far more concerned with their bottom line than with any of those pesky questions we might have.

Hey, look—we’re not saying that the pharmaceutical companies and femcare manufacturers are evil per se, or that their decisions are necessarily driven by some deep-seated misogyny or sexism. But business is business, and as of 2001, the so-called feminine hygiene business was a cool $2 billion industry—and that’s just for the products themselves, not including related drugs or advertising.

Whether we’re aware of it or not, our relationship to menstruation is one that has been brokered not in our own homes, but at the supermarket, the pharmacy, and the doctor’s office. The conversation about menstruation (if you can call it that) is strictly one-sided and has been smoothly co-opted by big business, with a little help from religion, history, and society … and boy oh boy, do they have a lot to say.

So what can we do?

We can start by setting aside all the judgment and reexamining some of those crazy-making questions we’ve been ordered by society to be obsessed with since girlhood. (Do I smell? Does my pad show? Am I leaking? Did Harry from Accounting notice when the tampon fell out of my handbag?) How about we start asking other questions that are a lot more relevant to our lives today, like: Am I healthy? Is what I’m experiencing normal? Am I making the right choices for my body, my love life, my lifestyle, my planet? What’s right for me? Am I teaching my daughters, my grand-daughters, my kid sister good lessons about being a woman?

Enough with the ignorance and shame already! We say it’s high time for a little more transparency. Let’s perform a communal end run around the usual secrecy and embarrassment. Let’s wrest control of this deeply personal topic away from the forces that have controlled it for so long. Armed with information and insight, maybe we can even figure out how to bring up the subject in polite company, without dying of mortification. Perhaps that way, we can spark a truly meaningful dialogue with ourselves, our friends, and our families about this most basic of functions … and how it affects us all.