Flyaway (16 page)

Authors: Suzie Gilbert

STRANGE ALLIANCES

“Here,” said Mac, handing me a small wad of one-dollar bills. “You can have it for the turkey.”

“What a great kid you are,” I said, giving him a hug. “Thank you. But let me see what I can come up with before I take your money.”

I went to my desk and started shuffling through the piles of books and papers, searching for my Willowbrook Pharmaceutical Index and hoping it might have a hidden chapter on where to get cheap drugs. Coming up empty-handed, I pulled out my blue three-ring binder entitled “

DRUGS

” and riffled through it: “Avian antibiotics, from A to Z.” “Corticosteroids, use of. Dosage charts.” “Pain medication.” “Worming medicine.” Nothing. I picked up the notebook I'd taken to the conference. Its pages were covered with my ragged script, its pockets crammed with lecture handouts and flyers from various rehab centers. I skimmed through my notes: “Effects of lead poisoning.” “Treating bumblefoot.” “Songbirds and homeopathy.” “Basics of parasitology.” Just as I started wondering if the turkey and I should head for Canada, something caught my eye.

call Erica Miller DVM T St BR for chp itcnzle

AZ 1/10 cost, will overnight

I flashed back to a large lecture room where Dr. Erica Miller, staff veterinarian of the reknowned Tri-State Bird Rescue in Delaware, was giving her talk on avian antibiotics. Drugs can be prohibitively expensive, she had said, but there was a pharmacy in Arizona that sold compounded (mixed into a liquid or gel) medication for a tenth of the regular price. I lunged for the phone, called Tri-State, and scribbled down the number. Filled with sudden hope, I dialed Pet Health Pharmacy.

“Cipro and itraconazole,” said the cheerful woman who took my call. “A month's worth of the two prescriptions. Let's seeâ¦that would come out to about eighty dollars.”

“No!” I said, awestruck.

“And did you say you were a rehabber?” she asked. “Because we give discounts to rehabbers.”

“Life just keeps getting better,” I said.

Not everyone was impressed with my discount.

“Eighty dollars?” said a doctor acquaintance. “That's still a lot of money when there's a chance somebody's going to shoot her.”

“Don't give me that,” I replied belligerently. “Say you're working in a clinic in a dangerous neighborhood and I come to you with pneumonia. Are you going to refuse to treat me because there's a chance I might get mugged on my way home?”

“No,” he replied. “I'm going to refuse to treat you until you're wearing a proper straitjacket, like you should be right now.”

Three days after the medicines arrived the turkey's loud wheezing and coughing were gone, and from then on it was just a question of keeping her somewhat calm until her lungs healed. When I put her in the flight cage she paced endlessly back and forth, wearing a trench in the dirt, instead of lounging around gaining weight as I'd requested. Most days I let her loose in the shed. If she felt like it, she could move around on the floor, where she had no view of the woods. If she wanted a view, she could hop up on the table, but she

had to stand still in order to look out the window. This worked relatively well, until the turkey vulture arrived.

As always, it began with a phone call. “It's a great big vulture,” a man's voice said indignantly, “and somebody shot him.”

Rehabilitators dread the start of hunting season. On the one hand, you have the conscientious hunters who know the woods, eat what they hunt, and wouldn't dream of shooting a protected species. On the other, you have the drunken idiots who are just out there to blast whatever has the misfortune to cross their path. The turkey vulture I eventually found huddled next to an old house in Westchester had obviously met up with one of the latter.

Turkey vultures, along with their smaller cousins, the black vultures, are smart, funny, and sociable creatures. As they soar through the air they rock gently back and forth, like huge black butterflies, and they greet a bright morn

ing by perching together and spreading their wings like an ancient clan of sun worshipers. I find large groups of circling vultures so exhilarating that I become a dangerous driver; when my kids are in the car with me, they respond to the sight of vultures with howls of “Watch the road!”

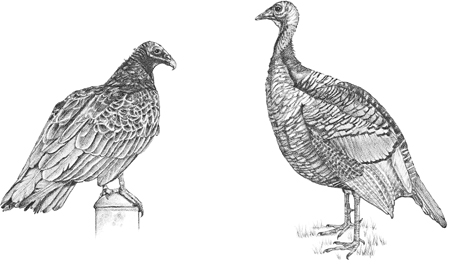

Turkey Vulture and Wild Turkey

“The jury's out on this one,” said Wendy, after X-raying the Westchester vulture, removing several shotgun pellets, and thoroughly cleaning and setting his wing. “The bone is splintered, so we'll have to see how it heals. There might be nerve or tendon damage. But it's worth a try.”

Turkey vultures look like wild turkeys designed by Tim Burton. Both are large birds with unfeathered, wrinkled heads. But turkey vultures, so named because of their resemblance to wild turkeys, strike the average person as more sinister because of their black plumage, smaller eyes, ivory-colored hook on their beaks, and the superstitious nonsense that has dogged them ever since humans started making it up. Sure, vultures eat dead things; the last time I looked, so did

Homo sapiens

.

I put the turkey in her large crate on one side of the shed and the vulture in another large crate on the other, so each had a window. The settling-in period for vultures can be difficult. Some are immediately matter-of-fact about dealing with humans; others are horrified by the very idea. This particular vulture fell into the latter category. For the first two days he would greet me like a drunken frat boy caught by the college dean: he'd eye me with alarm, empty the contents of his stomach, then regard me reproachfully, as if the whole sad state of affairs was beyond his control and entirely my fault. Except for my twice-daily hospital rounds, I stayed away from the shed. Yet in spite of my lurid descriptions, the new patient had two determined visitors.

“Awww, come on, please let us see him,” begged Skye. “Pleeeeeeeeeze!”

“We'll be so calm and quiet and we won't upset him at all, we promise!” said Mac.

“Don't say I didn't warn you,” I said, leading them into the shed, where the vulture took one look at us and heaved up a good-sized pile of partly digested venison. We all turned, closed the door, and trudged silently back to

the house. “Can you drive me to Cindy's house?” asked Skye. “

Her

mom is a hairdresser.”

By the third day the vulture had decided that I was a relatively benign figure who brought food and didn't hurt him, and from then on he would vomit only when he was forced to undergo something he considered truly ghastly, like a bandage change. For the daily cleanup I would open the crate door, step to the side, and poke a thin stick through the back panel; the vulture would step away from the stick, out of the crate, and into a small pen. We'd studiously ignore each other while I shuffled bowls and newspaper, and during those few occasions that I caught his eye I'd immediately drop my gaze, thus proving that I was far more scared of him than he was of me. Since a large percentage of injured wild birds eventually die from the stress of being in captivity, the vulture's growing comfort level was a milestone in his recovery.

I roped off a third of the shed and hung a large sheet as a privacy curtain, so the turkey could come out of her crate and have some space to move around. Eventually she finished her medication and I began putting her in the flight cage during the day, when it was warmer, and bringing her in at night so she could continue to gain weight.

After two weeks Wendy took another X-ray of the vulture's wing. The X-ray showed calcium forming around the shards of his splintered bone but not enough to leave the wing without support, so she wrapped it for another week. He was doing well, though, and needed space, so I put him in the left side of the flight cage and set up a heat lamp in a corner where he could go to warm up. He was obviously happy to be out of the crate. He walked around, tested out the low perches and logs, stretched his good wing, and continued to eat heartily.

But the status quo never stays so for long. “Hey, Suzie?” said Joanne through the phone. “Can you overwinter a couple of pigeons in your flight?”

If a bird is injured in the autumn and recovers, it often means the rehabber will still have to “overwinter” him, or keep him until spring. A migratory bird normally in Costa Rica for Christmas can't be booted out into the snow and

be expected to survive. Even birds who spend the winter in harsh climates are sometimes kept through the winter, as letting them go in the spring will give them a better chance. This means that there are many healthy birds biding their time until spring, and many rehabbers wishing they didn't have to spend the winter cleaning up after them.

“I guess,” I said. “Who do you think they'd rather have as a roommateâa wild turkey or a turkey vulture?”

“They don't care,” said Joanne. “They're pigeons.”

I posed the question to the family. “Put them in with Wavy Gravy,” said Skye. “Because the vulture might get nervous and throw up on them.”

“But the turkey is leaving soon,” said Mac. “Put them in with the vultureâhe needs some company.”

“Put one in with the turkey and one with the vulture,” said John.

“How about if I put them both in the bathroom?” I said.

“Don't even joke about that,” said John.

Mac had a point: the turkey would be leaving soon. The vulture was well-fed, had plenty of space, and vultures are not an aggressive species. The pigeons could fly while the vulture couldn't. And, as any soldier will confirm, odd alliances can be formed when you're in a captive situation. Why not give them a chance? I propped their crate door open, and the pigeons walked busily into the flight cage.

Pigeons look surprised even if there's nothing going on, so it was a little hard to tell just how undone they were by the sight of a large turkey vulture in close proximity. After a single frozen moment they flew up onto a high perch, where they sat staring at the strange creature below them. The vulture stared back with his usual look of wary interest, but didn't seem particularly impressed.

As the days went by, the pigeons became more intrigued by their flightmate. Despite their bad publicity, pigeons are curious and intelligent birds. They are successful and adaptable without being aggressive toward other species; they have complicated and interesting relationships; and they simply love to fly, as anyone who has ever seen a flock wheeling through the sky can attest. The two

in the flight cage seemed irresistibly drawn to the mysterious vulture: the first day they stayed high above his head; the next day they perched just slightly above him; and by the third day all three were sitting on their own tree stumps, each no more than a few feet apart. I'd peer into the flight cage and see the vulture walk regally past me, followed by the pigeons, like a rock star trailed by his fans; unable to stop ourselves, we dubbed them Jerry Garcia and the Deadheads.

Jerry's shattered bone healed slowly, and there was permanent soft tissue damage. While the wing was immobilized, the injured muscles and tendons contracted further, eventually preventing him from extending it more than halfway. I'd appear each morning (when his stomach was relatively empty), toss a small towel over his head to calm him down, then sit on a log and slowly and carefully extend and retract the wing, hoping the tendons would stretch and regain some of their elasticity. No one appreciated my efforts, of course; the Deadheads would fly to a high perch and watch me with suspicion, and every once in a while Jerry would snake his beak out from under the towel and bite my hand. Although vulture bites can be quite painful, they are not in the same league as, say, pet parrots, who can practically sever your finger when they're in a bad mood.

Eventually it became clear that Jerry's soaring days were over, and I found him a home at a sanctuary that was looking for a companion for their single vulture. I tried to include the Deadheads in the deal, but they turned me down. The flight cage seemed empty without Jerry, who would eventually forge a companionable bond with the sanctuary's vulture. For days the pigeons wandered forlornly around the flight, two little groupies deprived of their rock star. All they really needed was the company of their own kind, and before long their own kind began to arrive. In spades.

But meanwhile, Wavy Gravy had became more and more rambunctious, making it clear that she considered it time to go. When her release date finally arrived, I called Bonnie.

“Your turkey's all set,” I said. “I didn't think this day would ever come. I want to release her back into her flockâwhat time do they show up?”

“They don't,” said Bonnie. “They've moved on. I haven't seen them for weeks.”

I called everyone I knew in Bonnie's area; no one had seen the turkeys. I called my other birding friends, thinking a strange flock would be better than no flock at all, and fared no better.

“I don't know what I'm going to do with her,” I said to my friend Diana Swinburne. “I can't find her a flock, and I don't want to release her completely alone.”