Folklore of Lincolnshire (22 page)

Read Folklore of Lincolnshire Online

Authors: Susanna O'Neill

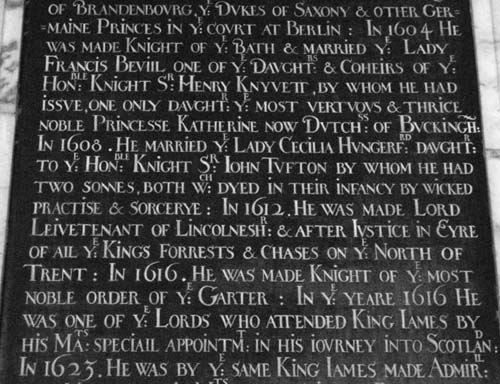

In 1608 he married ye lady Cecilia Hungerford…by whom he had two sonnes, both who died in their infancy by wicked practise and sorcerye.

All counties had their own superstitions about how to avoid the evil eye of a witch. Ethel Rudkin explains some of the local Lincolnshire ones:

In the presence of a witch, so that she shall be powerless against you, clench both your fists with the thumb inside and under the fingers.

If you are bewitched take a lock of hair from low down on the nape of your neck, take another lock from your body, and bury these with needles and pins.

If you pluck a straw from the thatch of a witches’ house and hold it in your hand, a witch can’t harm you.

The tomb of the Earl of Rutland, on the right-hand side within the church of St Mary the Virgin, Bottesford.

A close-up of the inscription above the Earl of Rutland’s effigy, explaining how his sons were killed through witchcraft.

If you think that anyone who is ailing is in reality bewitched, then fill a bottle with the sufferers’ urine and put needles and pins in it and bury it. This will fairly ‘tie the witch up’, for she won’t be able to pass water naturally until that bottle is broken.

2

This idea of a witch bottle is a very old device, used to deflect evil energies. Traditionally, once filled with the sufferer’s urine, hair, or nails, it was then buried under the hearth or in a secret wall space. Another method was to throw the bottle onto a fire, which broke the spell the witch had cast.

In 2003 there was a remarkable find under some old foundations in the small Lincolnshire village of Navenby. A couple doing some renovations on their house dug up a bottle which seemed to contain bits of metal. They had no idea what it was and put it in a cupboard, eventually taking it along to an open evening at the archaeological department at Lincolnshire County Council.

It was immediately recognised as a witch bottle and dated to the 1830s. It had been damaged, but still had its contents; hair, pins and possibly urine. Adam Daubney, the Finds Liaison Officer said it was an amazing discovery, especially as they thought such superstitions had died out by then. He did state that in the more remote rural areas, old traditions do tend to linger for longer. The bottle is being preserved at Lincoln’s Museum of Lincolnshire Life.

Gutch and Peacock say that around 1817, ‘a great heap of pins and old fashioned tobacco pipe heads’ were found on Hardwick Hill, Scotton Common, ‘believed to have been put there for magical purposes’.

3

This is further evidence of the beliefs from this era.

There were various other techniques for trying to ward off the curse or evil eye of a witch. Codd relates the account of a witch from Willoughton who had a reputation for cursing. A certain Mrs Smith decided to invite the witch, Betty, round one day, giving her the best seat in the house to sit upon. When Betty sat down, however, she soon jumped up in pain, as Mrs Smith had hidden pins under the cushion so as to draw the witch’s blood and thus deny the witch any power over her. Gutch and Peacock relate the same story happening to a poor old lady, Nanny Moody, from Messingham. She too was tricked into sitting on a chair laced with pins and had a very sore behind for a long time afterwards. She had apparently suffered other incidents from her fellow villagers, who believed she was a witch, but whether she was or not was never confirmed.

This idea of drawing a witch’s blood was worryingly popular; Codd tells the story of a pig farmer who complained to the local priest that his pig had been overlooked at market. ‘Thou and me knaws the party that hes dun it…’

4

he apparently said, declaring that if only he could draw the blood of the witch then all would be well. What a shocking state of affairs that any woman, young or old, could be charged with being a witch, on the flimsiest of evidence and, like Nanny Moody, be persecuted her whole life.

Other remedies to keep a witch at bay included hanging the skin of a toad on top of a post near the house, or hanging mistletoe above the doorway. The practice

of bottling some pins, black apple-pips and hair, then putting the sealed bottle on a hot fire until it burst with heat was a common one. When the glass broke the hex was said to be broken. The wicken tree was used as a tool for warding off evil advances, but the bay and elder were also thought to each contain certain properties to keep a witch away. Gutch and Peacock wrote that mountain ash or rowan twigs (wicken) were carried in pockets, as a charm against witches. Apparently, to avoid having one’s pig cursed, you should hang a garland of wicken branches around its neck, then it could not possibly be bewitched.

The witch bottle found in Navenby, kindly shown to me by the staff of Lincoln’s Museum of Lincolnshire Life, where it is housed. (Reproduction of photograph permitted by Lincolnshire County Council: Museum of Lincolnshire Life.)

An example of a witch ball, also held by Lincoln’s Museum of Lincolnshire Life. These were apparently hung up in windows to deflect the evil eye, and thought possibly to be the forerunner of Christmas bauble decorations. (Reproduction of photograph permitted by Lincolnshire County Council: Museum of Lincolnshire Life.)

Examples of ‘witch stones’, These were stones with a natural hole in them and were thought to have been used as protection against curses.

Gutch and Peacock list a few things people used as charms against witches, including hanging the insides of a pigeon over the door of the house or hanging a horseshoe over the stable door. Iron was often thought of as a weapon to deflect the evil eye, hence the widespread use of horseshoes as ‘lucky’ charms. Pins and nails worked well too, and a cake stuck full of pins was a good counteract. Cowslips were also thought to be a protection against witches. Witch stones, a stone with a natural hole through it, found accidentally, should be hung in the doorway of a house for protection.

Witches were said to ‘eyespell’ the first money that a labourer was paid on hiring day, but the men could counter this by spitting on the money or placing it in the mouth.

5

Lincolnshire was better known for its cunning folk, than for its witches. A Cunning Man was more often seen as a healer, although there was always the fear that he could harm as well. They were more popular than was first thought, although their numbers dwindled considerably during the witch hunts. Charles Kingsley uses this common knowledge of Cunning Men or Wise Women in his novel, when Torfrida asks her nurse to use a charm to discover the mark under her admirer’s beard. He also highlights the common belief that witches haunted the Lincolnshire Fens, when Torfrida replies, ‘Well, if it keeps off my charm it will keep off others – that is one comfort; and one knows not what fairies, or witches, or evil creatures, he may meet with in the forests and the Fens.’

John Parkins was a well-known Cunning Man who plied his trade in Little Gonerby. He apparently built up quite a business for his charms and protections, calling his establishment The Temple of Wisdom. It is thought that he was an apprentice of the famous Francis Barrett, who tried to revive interest in magical activities after the hunts. As well as protection against witchcraft, Cunning Folk could be fortune tellers, healers and dealers in love potions; some were even said to locate buried treasure.

Wise Men and Women were often called upon by villagers to help them with some problem or other, when the situations arose. Often they were approached by people who believed they were suffering from the curse of bad witchcraft.

Gutch and Peacock illustrate this with a story from Yaddlethorpe about an old man, Thomas K, who was shunned by the entire village, as they suspected him of having the evil eye.

6

Among his crimes were causing rheumatism, cattle to die and pigs not to fatten. His neighbour decided to do something about Thomas K when

he found his show horses dead the morning of Lincoln Fair. He visited a Wise Man, who told him to cut out the heart of one of the horses, stick pins into it and boil it. Whilst he was doing this he should expect Thomas K to come knocking at his door, but under no circumstances was he to let him in. The neighbour did all this and apparently Thomas K did come knocking, as predicted, and tried every means possible to enter the house. It was securely locked, however, and the result was that Thomas K became very badly scalded, so much so that he could not work for months.

Another incident is mentioned regarding a lady from the Covenham area, who had been bedridden with a sickness for some length of time. She spread word that she was going to call for the Louth wizard to visit her and aid her recovery. It is said that the very same day she declared her intentions, she was suddenly cured and able to leave her bed. The thinking was that she had been under the influence of some evil eye and that they had lifted the curse, fearing the potential actions of the Wise Man of Louth.

The wizard of Lincoln, known as Wosdel, was called upon one time by a farmer who had been robbed. Wosdel visited, in the form of a blackbird, and showed the farmer the two farm workers who had stolen from him. The men were arrested and the money was eventually found hidden at one of their homes.