Folklore of Yorkshire (13 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

The fairies’ need for human children is well known and once again, despite their aversion to humans intruding in their affairs, the fairies were more than happy to take great liberties when it came to ours. As the folklorist Katharine Briggs notes, ‘So far as respect for human goods is concerned, honesty means nothing to fairies. They consider that they have a right to whatever they need or fancy, including the human beings themselves.’ Indeed, they seemed to desperately require human children every now and then to keep the fairy stock healthy, and showed no qualms about stealing them as they chose, often leaving an unhealthy specimen of their own in the infant’s place. This so-called ‘changeling’ is one of the most ubiquitous fairy motifs and undoubtedly arose to explain developmental disabilities in less enlightened ages.

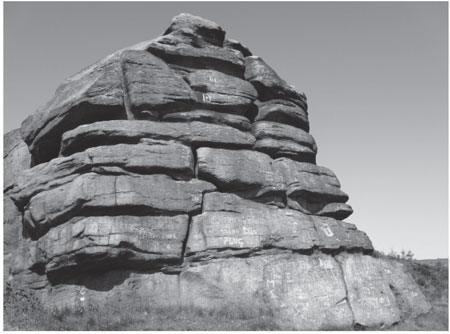

The changeling belief appears to have been strong in Wharfedale during the early nineteenth century and the fairies of Almscliffe Crag were especially feared as child-stealers. During the early part of that century, a farmer named Bradley lived in that region and he was convinced that three of his children were changelings. According to one source, ‘Three of his sons, and two of the daughters were fine, tall men and women, who married early and well; but the three changelings were dwarfish, crooked and ill-tempered, and never married.’ These three ‘changelings’ were still alive around the 1850s, and a writer for the

Leeds Mercury

in 1885 recalled gawping at Tom and Fanny Bradley during his childhood. Even then the rumour endured that their mother had left her real children unattended in the vicinity of Almscliffe Crag and had been left with changelings in their stead.

Almscliffe Crag in Wharfedale, home of child-stealing fairies. (Kathryn Wilson)

Fairies undoubtedly bore their own children. According to one report, a farm-girl once stumbled across such an infant on Fairy Cross Plain: ‘It was lying in a swathe of half-made hay, as bonny a little thing as you’d ever seen. But it did not stay long with the lass that found it. It sort of dwindled away and she supposed the fairy-mother could do without it any longer.’ Perhaps, however, they were not all as healthy as that one; or perhaps complications often developed during the birth, as one of the most curious requests fairies made of humans was for the services of a midwife. Again, this is an old and widespread migratory narrative, a version of which was recorded by Gervase of Tilbury in the twelfth century.

In Yorkshire, the legend is attached to Keighley market. One day, a stunted grey man approached a butter-wife at her stall in the town and pulled at her apron, gesturing that he needed her to assist his pregnant wife. The woman followed him, but curiously all those who saw her leave insisted that she had been alone and she retained no memory of the journey. At length, she found herself in a limestone cavern where she helped deliver a child from a similarly stunted and grey woman. Following the birth, the mother took a crystal phial and anointed the eyes of the infant; before she left, the butter-wife was sure to appropriate a drop for herself, knowing it to offer the gift of second sight.

The little man presently returned her to Keighley and left her with a bag of fairy gold for her trouble. But thanks to the liquid she had stolen, she had a greater reward: the ability to see the little people permanently. Unfortunately, it was not to last. Several weeks later, the butter-wife saw the stunted grey man again, stealing a bag of corn from the market. She asked after his wife and child, which startled the fairy and he jumped up on her stall. ‘Which eye see you with?’ he demanded, and the butter-wife pointed at the eye into which she’d dropped the liquid. The fairy then blew in that eye and vanished, after which the butter-wife never saw such a being again.

This story nicely exhibits the fairies’ double standards; they were quite happy to exploit a human’s midwifery skill and steal corn that men had harvested, but as soon as their own domain is threatened, they take action to eliminate the danger. Curiously, the fairy-midwife legend was clearly still circulating in the rural areas of North Yorkshire into the twentieth century. In a study of latter day fairy accounts, Katharine Briggs records the story of a district nurse who was supposedly taken by a diminutive man to deliver a child in a hut somewhere on Greenhow Hill – the wild expanse of moorland which rises between Wharfedale and Nidderdale. Naturally, she was never able to find this hut again.

That such a narrative survived into the last century is further proof of the enduring power of the fairy faith. As Katharine Briggs observes, ‘English fairy beliefs … from Chaucer’s time onwards have been supposed to belong to the last generation and to be lost to the present one. The strange thing is that rare, tenuous and fragile as it is, the tradition is still there and lingers on from generation to generation substantially unchanged.’ Yet in some ways, it seems appropriate for the educated observer to regard fairy

belief

as a relic of the past, as it echoes the strong association between the fairies and the remains of our ancestors that prevailed amongst fairy believers themselves. Whatever the fairies might be, they have always existed on the fringes of the temporal landscape and perhaps they will continue to dwell on that threshold for many generations to come.

T

HE

D

EVIL

![]()

T

he Devil occupies a prominent place as an antagonist in the annals of local legend; a scarcely surprising position considering the emphasis which both medieval and post-Reformation Christianity gave to his persisting influence. Indeed, whilst most of the denizens with which folklore populated the countryside seem to have represented a parallel current of belief to Christianity and were often condemned by the Church, legends concerning the Devil may well have been sanctioned or even generated by ecclesiastic agencies. Whilst the subversive hand of vernacular belief can be detected in some of these narratives, by and large they appear consistent with the tenets of orthodox theology in England from the Middle Ages onwards.

In Yorkshire, the category in which the Devil most commonly appears is the landscape legend. Prominent topographic features and ancient megalithic structures are frequently attributed to the actions of His Satanic Majesty, much as they are sometimes attributed to the work of giants. For instance, like Wade, folklore credited the Devil with a supposedly Roman highway – in this case, Dhoul’s Pavement which climbs over Blackstone Edge. The similarities between the Devil and giants in folklore are such that many have suggested that the Old Nick was imposed onto earlier indigenous giant legends, thereby creating a narrative more palatable to the Christian authorities. Discussing perceptions of prehistoric monuments in the medieval period, archaeologist Richard Hayman asserts, ‘The Devil replaces giants in English folklore just as Arthur does in Welsh folklore.’

There are certainly some landscape features which are associated with both giants and the Devil, suggesting that the two narratives existed side-by-side and possibly their respective popularity was determined by class or locality. Almscliffe Crag in Wharfedale was supposed to have been thrown down either by the Devil or by the giant Rombald’s wife. Meanwhile, a stone at Scar Top in Netherton near Huddersfield, is imagined to bear the footprint of a Magdale giant, left as he frantically searched for his missing daughter (

See

Chapter Four); or alternatively the hoofmark of the Devil as he leapt from there to the summit of Castle Hill.

Dhoul’s Pavement over Blackstone Edge, an ancient highway constructed by the Devil. (Kai Roberts)

The Devil and giants also feature as rivals in some narratives. In one version of the legend, the rock which became Almscliffe Crag was originally thrown by the Devil at the giant Rombald during a fight on Ilkley Moor, overshooting its target by the substantial distance of eight miles. A little further north, the two adversaries pelted each other with rocks across Raydale. A stone thrown by the giant came to rest on the shore of Semer Water and is known as the Carlow Stone, whilst the stone hurled by Satan in response landed high on the slopes of Addleborough. Today, this earthfast boulder is still called the Devil’s Stone and his claw marks are supposedly visible on the rock.

Such petrosomatoglyphs (supposed images of body parts imprinted in stone) are a common feature of both giant and Devil lore. In addition to Scar Top, the Devil also left his hoofmark on rocks at Baildon and Rivock Edge in West Yorkshire, both known as the Cloven Stones. These sites are not associated with detailed legends, but one unique tale from West Yorkshire relates how the Devil made a wager with God that he could stride across the Calder Valley from Stoodley Pike to Blackshaw Head. If he won the bet, he could claim all of the souls living in the dale below. Fortunately for the folk of Hebden Bridge and neighbouring towns, just as he was at full stretch, the Devil lost his footing and tumbled down the valley side. As he fell, his hoof nicked the face of a huge gritstone buttress known as Great Rock and that cleft can still be seen running up its surface today.

Great Rock in Calderdale, split by the Devil’s cloven hoof. (Kai Roberts)

Prehistoric burial cairns are also sites often associated with both giants and the Devil. Little Skirtful of Stones on Ilkley Moor is attributed to the giant Rombald’s wife and His Satanic Majesty. A similar, albeit less well-preserved, Bronze-Age cairn called Devil’s Apronful can be found on the moors above Appletreewick in Wharfedale. Legend tells that the Devil was carrying stones in his apron to fill up Dibb Gill across the valley, when he caught his foot on Nursery Knott and spilled them near Simon’s Seat, where they still lie today. It is also said that if any of the stones are moved from this cairn, they will return to their original place overnight – a common motif in folklore connected with prehistoric monuments.

Yet, whilst local legend tends to credit giants with any immense topographic or megalithic feature, the folklorist Jacqueline Simpson has observed that sites associated with the Devil conform to a more noticeable pattern. She writes, ‘Many legends ascribing landscape features to the malevolent or stupid actions of the Devil relate to unproductive areas and objects … Popular legends ascribing these unwelcome features to an evil or stupid being were a way of relieving God from the responsibility of having created them.’ In Yorkshire, this tendency is even visible on a smaller scale, as farmers often called a poor stretch of pasture the ‘Devil’s field’ and deliberately left it uncultivated so that the fiend would not interfere with the rest of the crops.