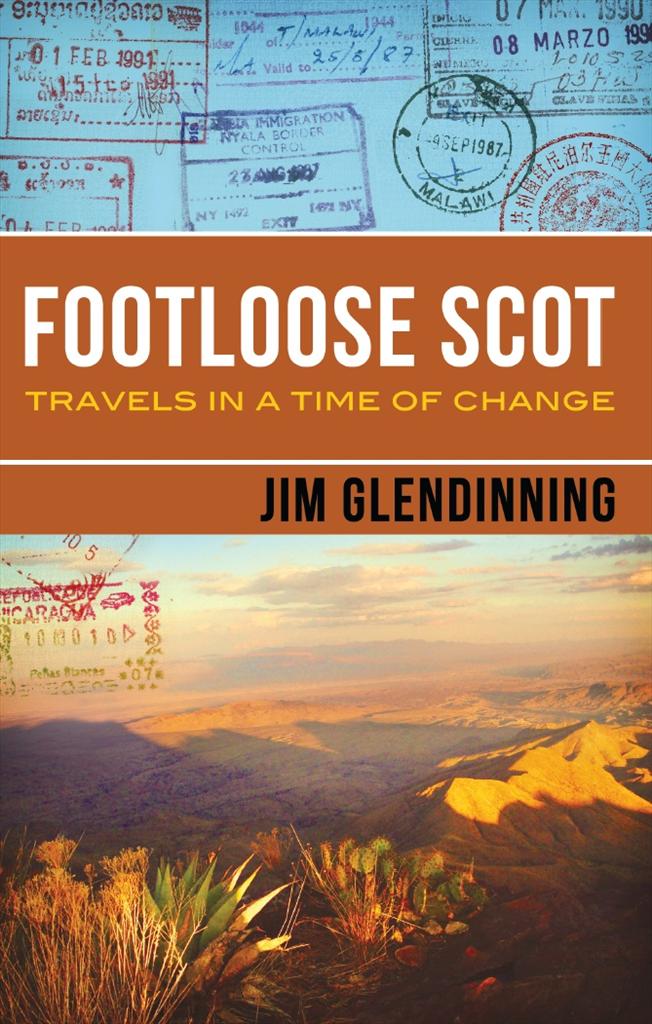

Footloose Scot

Authors: Jim Glendinning

TRAVELS IN A TIME OF CHANGE

JIM GLENDINNING

Copyright © 2012 by Jim Glendinning

Mill City Press

212 3rd Ave North, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401

612.455.2294

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

Photo Credit: Romayne Wheeler (Chapter 15) by Pilar Pedersen.

ISBN: 978-1-62652-060-8

For my sisters Nora and Jean, and in memory of our late brother David

_______

I have been very lucky in being able to satisfy my travel itch over many years and in many places. I have also often been employed in the travel/hospitality industry and have been able to travel at someone else's expense. If this book persuades the reader to travel a little more adventurously or imaginatively and with a concern for other cultures, then I will consider its job done.

The growth in mass tourism has been truly staggering, and looks set to continue. Tomorrow's inquiring traveler will have to work harder to find undeveloped destinations or pristine wilderness to enjoy any satisfaction. I hope this book may also present some ideas.

I'd like to thank Tony Beasley for literary encouragement, Bailey Moyers for maps and photo enhancement, and Danielle Gallo for erasing many errors; those which remain are my fault.

Jim Glendinning

Alpine, Texas

SOLO TRAVELER

_______

1958

HITCHHIKING EUROPE

On January 25, 1958 I stepped off a Channel ferry in Calais, France heading for a youth hostel in Rosendaël close to Dunkirk, twenty-four miles distant. I was twenty. My first solo travel adventure was beginning and I was partly excited, partly nervous. I had spent a month preparing for the trip. I had an International Youth Hostel card and a new British passport with a message inside the front cover to "all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance." The day was bitterly cold and scudding snow clouds blew in from the North Sea. Surprisingly, the conditions proved useful, since the only ride I got was with a woman who wanted me as ballast in her car on the icy roads. No one else was stopping.

The hostel guardian in Rosendaël seemed surprised to have a visitor as he checked me in and pointed to the men's dormitory. The temperature was below freezing and the hostel empty. In the men's dormitory I pulled apart two mattresses that had been stacked on one of the beds and found a single dried black turd lying between the two. I was too cold to complain or even be disgusted. Putting on all my clothes, grabbing a few blankets and a clean mattress, I climbed into my sleeping bag for my first night in a foreign youth hostel.

How did I, a young man of privileged upbringing, get to this place? Raised on a sheep farm in the south of Scotland and educated at a boys' boarding school in Edinburgh called Fettes College, my life to the age of eighteen was comfortable and secure.

The farm where I was born was a dairy farm close to Lockerbie, and very close to where Pan Am flight 103 crashed fifty-one years later. Fifteen miles north in moorland and forest terrain was a sheep farm, Over Cassock, the ancestral home of the Glendinnings. This is Scotland's border country, called simply The Borders, home to families like Armstrong and Scott. The local clan is Clan Douglas, to which the Glendinnings belong. It is sheep grazing country, with rains of up to 60 inches annually, and home to the Border collie sheep dog.

The Romans had arrived in the area two thousand years ago and established the northern boundary of their empire, naming the wall they constructed after their Emperor, Hadrian. Immediately in front of Over Cassock farmhouse earthwork remains of a fort are visible, a clue to the region's history, much of which was warlike, as seen also in the many ruined abbeys, castles and battlefield monuments around the region. The families in the southern part of the region engaged in cattle rustling, raiding south across the English border, sometimes uniting to fight against English invasions.

The Glendinning family has a lengthy history. The name comes from Glendonwyn, a Norman family who arrived from France at the Norman Conquest in 1066. At one time the Glendinnings acquired substantial estates along the Border region but later, in a falling out with the Douglasses, lost these lands.

I was born in 1937 just before the start of the Second World War, with an elder brother and two sisters. My earliest experiences were connected to the war. My first connection to a world outside of our wet, northern countryside was the arrival in early 1944 of the 15

th

Scottish Division of the British Army preparing for the D-Day invasion of France. Our farm was part of their training ground. They dug underground shelters and slit trenches, covered their tanks with tree branches and netting, fired their guns and cooked up meals on small field stoves, some of which they shared with a wide-eyed six-year-old.

During the war years, our farm was regularly supplied with prisoners of war (POWs) housed in nearby camps and brought to local farms for day work. We established an easy relationship with the German POWs, one of whom carved model planes out of wood for us children. We even continued the relationship by correspondence long after he was repatriated to Germany. We were, however, glad to see the backs of the Ukrainian and Italian POWs, who stood around, cold and miserable, in the muddy fields where they were meant to be picking potatoes, and whom we thought were lazy.

With the ending of the war we met a POW from our own family. An uncle, a lieutenant colonel in the Indian Army who had been captured in North Africa by Rommel's troops, was released from a German POW Camp. We hung flags and discussed whether to write "Welcome Home" or "Welcome Back" on our homemade sign, and settled for the latter since our house was not strictly his home. He looked gaunt and seemed a little bemused by the family welcome, but we soon got used to him and, with probably much more difficulty, he settled in to post-war Britain.

Around this time we also met a family war hero who was returning from duty in Southeast Asia. A first cousin, James Glendinning had fought in the British Army's guerilla campaign behind the Japanese lines in Burma, and had been decorated with a Military Cross, for "gallantry during active service," one of Britain's most important medals. We were desperately hoping to hear stories from him but were too shy to ask during his brief visit to our farm. Almost immediately he had to leave to deal with his own family matters. But his appearance in the flesh and the rumors of his heroic deeds conjured up for me the idea of distant places, colorful, hot and dangerous, and very far removed from the cool temperatures and familiar landscape of rural Scotland.

Sixty-five years later, my cousin the war hero, now in his eighties, was speaking to a group of Texans whom I had brought on a tour to Scotland. We were having dinner at a comfortable hotel in the small town of Peebles just south of Edinburgh. Cousin Jimmy, as I called him, had after demobilization from the army (demobbed was the colloquial term) been a lawyer and a teacher. His passion was and remained Scottish nationalism: independence from England.

At dinner that night, some in the group would have liked an explanation of why the Scottish Government had just released the man convicted of the Pan Am 103 explosion, a Libyan called Mahgrebi. But when Cousin Jimmy started talking with quiet conviction and dignity about his hopes for Scottish independence, no one liked to interrupt him. He died a year later, reticent to the end about his military career.

Describing my teenage years at a boys' boarding school in Edinburgh called Fettes College as comfortable needs some explanation. The schedule included cold showers every morning (even in the depth of winter), long training runs, boxing and rugby competitions, canings on the backside for infractions, and struggling to fix detachable collars onto starched white shirts on Sundays. These features probably had not changed since the founding of the school in 1870. But they became comfortable as one adjusted to them. And I can thank this Spartan upbringing during my teen years for being able, 50 years later, to sleep in the open on the bare ground and live on very few comforts.

At Fettes I was challenged, scholastically and on the playing fields, since the public school system (as these private boarding schools are called) was founded on the ideals of competition and leadership. I played rugby successfully until I got a knee injury, attained the status of 'school prefect' and passed three Advanced Level state exams. In my last year, I applied to Lincoln College, Oxford. I took a written examination, attended an interview, and was accepted for admission in 1958, two years later.

I had previously been abroad three times. At age twelve in l949, an aunt took me and her son by train on a short trip to Switzerland. We stayed at a pension in Interlaken, rode the train inside the Eiger Mountain up to 12,000 feet at the Jungfraujoch, saw the bear pit in Berne and visited French-speaking Switzerland at Neuchatel.

How different Switzerland was! The sun shone on clean streets. Taxi drivers smoked small cigars and drove American cars. Shops displayed mouth-watering pastries. Beyond the houses of Interlaken, which was on a lake, green pastures gave way to forested slopes with snow visible on the mountains in the background. This was a far cry from damp and grey old England, exhausted from the war.

The second trip was an exchange visit to Germany when I was sixteen. Few of the teachers at Fettes spoke of the merits of foreign travel, although the Church of Scotland minister took a group of older students on a camping trip to Spain. I studied French and German, and my German teacher suggested that an exchange visit would improve my German. So I travelled to Mannheim to stay with a family called Reschke, whom my teacher knew, and to meet my exchange partner, the younger son Jörg, a tall pleasant fellow who was my age.

This was a successful if short two weeks' visit and my German improved. Jörg's father was the Überburgermeister (Mayor) of Mannheim and the family was relatively affluent. This was less than ten years after the end of the Second World War but much of Mannheim had already been rebuilt. I was staying with a family for whom the suffering of the war years was a thing of the past. We didn't discuss it. Instead, we played tennis and drank beer.

I went with Jörg to his school in Westphalia for seven days, a Rudolf Steiner School. The Steiner teaching philosophy of combining academic, artistic and social subjects in a single curriculum was new to me, but seemed to be successful there judging from the upbeat mood in the school. By contrast, my own school focused on learning and equally rigorous sport, with a strong overall code of discipline. The attitude of the students was open and positive and I was readily accepted, despite the fact that the British Army was at that moment doing annual maneuvers in the area and their tanks were tearing up the countryside. There was little talk about the past, which perhaps was a pity since it might have told me something about German teenagers' thinking. But I didn't raise any questions, and they didn't volunteer any comments. Jörg came to my home in England the following year, and impressed everyone with his manners. His mother also came, a year later, and the exchange visit was seen as a success.

My third trip to the Continent also happened while at boarding school. I persuaded my mother to let me use her Morris Oxford station wagon for a camping trip round France. Four of us seventeen-year-olds got passports, a permit

(carnet)

for the vehicle, and maps, and loaded up with camping equipment. With hot weather, delicious food in the shops, and all of France ahead of us, the recipe was perfect. We headed to the Mediterranean coast, tried chatting up French girls with no success, discovered small beaches for swimming, got sunburned, and camped and cooked at a different spot each night. We discovered for ourselves the joy of the French picnic: buy a baguette, juicy ripe tomatoes, some charcuterie and a bottle of wine, drive off the main road to a quiet spot on a river bank or under a tree, and voilà.

Leaving school I expected to do National Service in the armed forces for two years. Conscription was general in those days. But, following an injury to my right knee when playing rugby, which three operations could not fix, I was rejected on medical grounds.

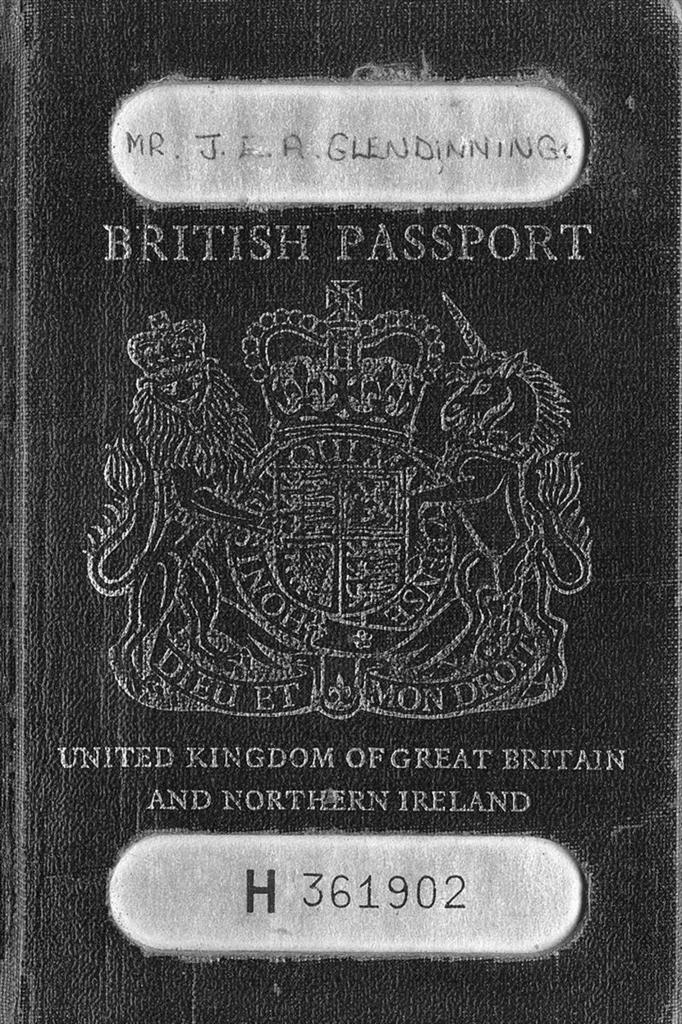

OLD BRITISH PASSPORT

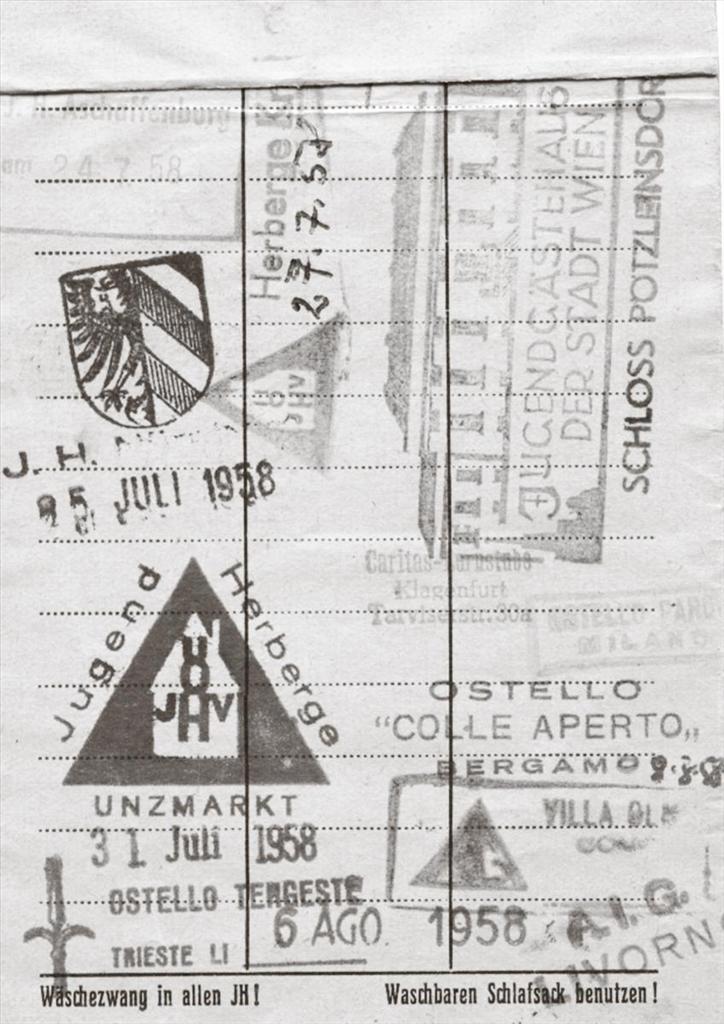

STAMPS IN YOUTH HOSTEL CARD

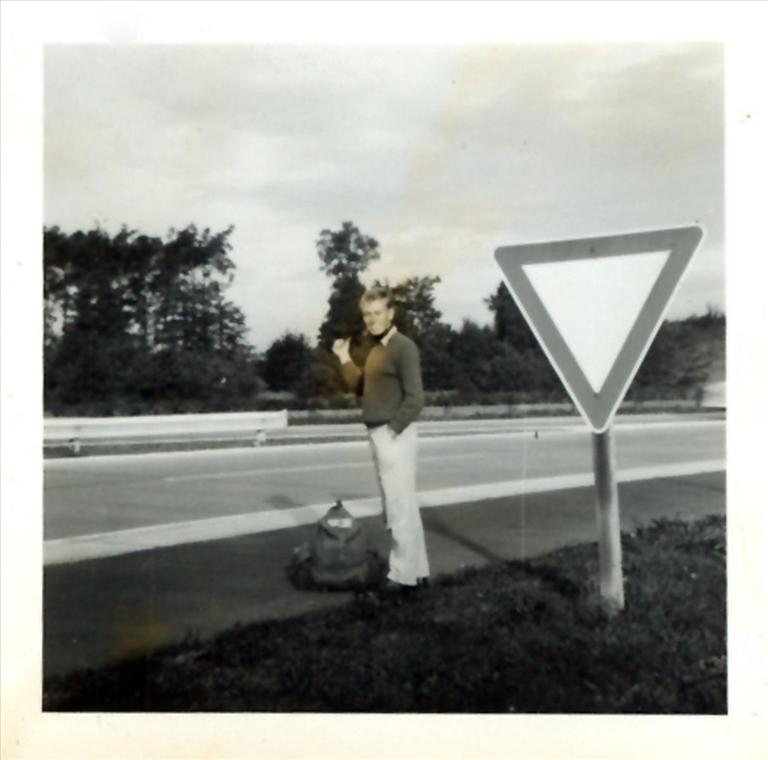

ON THE AUTOBAHN, 1958