Forbidden

Authors: Eve Bunting

Contents

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Afterword

About the Author

Special thanks to Professor Andrea Karlin

Clarion Books

3 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10016

Copyright © 2015 by Edward D. Bunting and Anne E. Bunting Family Trust

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

[email protected]

or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

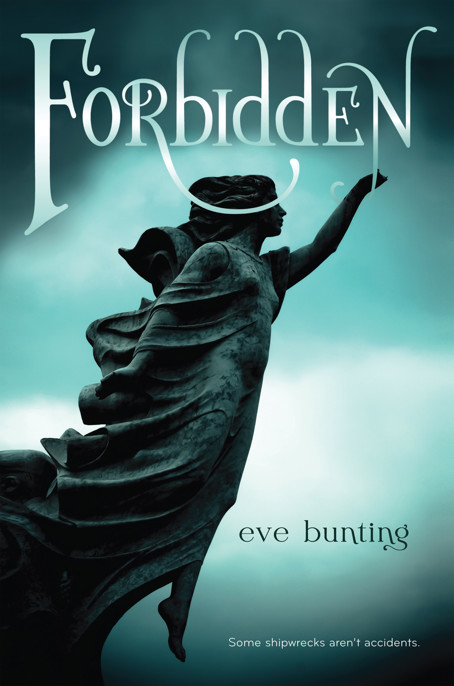

Cover photograph © 2015 by Tom Gatton/TommyVon Photography

Hand-lettering by Leah Palmer Preiss

Cover design by Christine Kettner

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Bunting, Eve, 1928–

Forbidden / Eve Bunting.

pages cm

Summary: “In early 19th century England, Josie, 16, finds herself in a sinister place with mysterious, hostile people, including her own relatives. Persistence and determination drive her to uncover the town’s horrifying secret—a conspiracy to wreck and plunder ships—despite obstacles natural and supernatural.”—Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-544-39092-8 (hardcover)

[1. Conspiracies—Fiction. 2. Supernatural—Fiction. 3. Orphans—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.B91527Fp 2015

[Fic]—dc23

2014043063

eISBN 978-0-544-39118-5

v1.1215

To Christine Bunting and

Richard Wohlfeiler

CHAPTER ONE

W

E HAD ARRIVED.

I’d taken two traps, a coach, and a carriage to get here from my old, beloved home in Edinburgh. It was sad and strange to think of myself as an orphan now that my parents had died. But that was what I was. Sorrow threatened to overwhelm me. But I told myself to be brave and to consider myself fortunate to have an aunt and uncle to go to. Though an orphan, I would have a family again.

We’d traveled through wind and rain that grew fiercer the closer we got to the coast. The journey had been tiring and difficult. And then there’d been the strangeness of the last village we’d gone through, where all the shops and houses were brightly lit, people stood around the street, music played loudly through the open doors of one of the establishments. It had seemed to me at first to be filled with gaiety. But only at first. There was a wrongness about it.

Robert, the carriage driver, rushed through it fast, the collar of his greatcoat half hiding his face, his gaze fixed on the road. The carriage bounced and shook so that I feared a wheel might come loose.

When he slowed to avoid a woman singing in the street, I’d gazed at the people around us. They had paused in their conversations and were staring at our carriage, staring at me, with such malevolence that my blood chilled. One man wearing a stained hat shouted, “What’s your business here?” in a truculent voice.

A woman yelled, “Go back where you’ve come from!”

Robert cracked his whip, and we were rattling away, the carriage swaying from side to side.

“This is Brindle?” I’d shouted up to him.

“It is, Mistress.”

“The people do not seem friendly,” I shouted, holding on to my bonnet to keep it from being blown away. I was going to Brindle Point, a more distant part of the town. Perhaps it would be better.

I’d thought Robert was not going to speak but then he shouted, “I do not know the people here, Mistress. I don’t come this way often.” He’d muttered something else, but I could not distinguish the words.

The wind had risen to a roar, shaking the sides of the carriage, flailing against the windows. It was difficult to make myself heard as I tried to communicate with him.

“How far now to my uncle’s house?”

“No more than a mile, Mistress. Maybe more or maybe less. I’m not from around here.”

We were quiet then, rolling unevenly on a road that seemed to grow steadily more narrow. Now and then, I heard the horses whinny, and I wondered about them. Could they see through the dark and wind? Were they exhausted? They needed to rest.

But now Robert was reining them in and the carriage was rumbling to a stop. He helped me to the ground, and I stared in dismay.

“This is the house?”

“It is, Mistress.” He tied the strings on his hat more tightly and wrapped his greatcoat more closely around himself before he lifted out my two boxes and my trunk and set them beside me. “If you’re sure you want to stay,” he said.

What was the matter with him? He had become jittery, casting anxious looks about him, hurrying in a way that told me he was eager to be off. Certainly the surroundings were not inviting. There was heather with no bloom on it, beaten a brickly brown. There was scrub grass, a tree snarled and crooked, bare rocky ground, clouds that hung low and menacing.

The rain had stopped falling, but the sky was still full of it.

“If that’s all, Mistress, I’ll be on my way,” Robert said.

I could scarcely hear him, for along with the roar and snarl of the wind, there was a boom of waves in the sea below us.

“Wait,” I shouted. “You are sure this is Brindle Point? And this is the house of my uncle, Caleb Ferguson?”

“It is, Mistress Josie. I made inquiries at the inn. See the name on the doorpost? Raven’s Roost?”

There was no hanging lamp at the door, but when I peered closely, I could make out the name and a date carved into the piece of plank:

RAVEN’S ROOST 1707.

The house had been there for exactly one hundred years. The board swung in the wind, banging itself against the door that was heavy and studded with nails, not at all in keeping with a house that I could already tell was battered and run-down.

A heavy bell hung on a rope beside it. When I looked up, I saw smoke twisting from the top of a chimney.

“But . . . but . . . my uncle is a professional man,” I shouted. “We passed the town a mile back.”

“Be that as it may, Mistress. This is his house. I’ll clang the bell for you, if you like, and then I’ll be off.” His soft Scottish burr blurred the words, and the force of the wind blew them away from me. He put a hand on my shoulder. “I was loath to bring you. And you can choose to turn around and come back with me. I’ll find you rooms—”

“Thank you,” I shouted. “That is kind of you.” My hair came loose from my bonnet, which, heaven knew how, was still on my head. I tried to push the long brown curls underneath it. “If I went back, what would I do then?” I held out my hand for him to shake. “Thank you, Robert. You have already been paid for taking me on this long trip?”

“Aye, Mistress. Your solicitor arranged all that. Would you no’ write to him and tell him you cannot stay and—”

The door behind us opened. Heat and smoke and light surged out. “I thought I heard you,” the man in the doorway said. “You’ll be Josie.” He addressed Robert. “Bring the lady’s valises inside and be quick about it. Is that her trunk? Make haste with it. The cold is perishing.”

“I can take the portmanteau . . .” I began, but the man, who I surmised was my uncle Caleb, said, “Let him do it and be on his way.” He walked ahead of me into the house.

For a time I could not get my bearings. The room was a blur, and I had to support myself with a hand on the wall. Behind me I heard the scuffle of Robert’s feet as he brought in my belongings. I heard the slide of my trunk being dragged across the lintel. I blinked hard. The smoke in the room was like a fog that stung my eyes and my throat. A woman in a plain black pinafore sat close to a fire that burned in an open hearth. Smoke billowed from it into the room. A steaming pot hung low over the flames. I stood uncertain.

“Here’s your niece, Minnie, come all this way to visit us,” my uncle said.

The woman was tall and bony, bent at the back as if used to standing under too low a roof. Her gray hair was fixed in a straggly bun. She moved toward me, and I held out my hand. My dear mother had always told me that ladies curtsy and men shake hands, but I could never bring myself to do that. Even though

Mrs. Chandler’s Book on Etiquette for Young Ladies

was strict on the subject.

My aunt did not take the hand I offered, merely stepped back. Her eyes were a glittering golden brown, small and hard as brandy-ball sweets. She was examining me the way a man examines a horse he’s thinking to buy.

“Mistress Josie?” That was Robert’s voice. I turned and saw him standing by my trunk, and I went toward him.

“Don’t forget,” he muttered. “My wife and I are in Glenbrae, eighteen miles back. Ask anyone the way. But be sure not to tell them you are niece to Caleb Ferguson.”

“Thank you, Robert. Thank you for your kindness.”

“Why are you standing blathering, man?” my uncle called out. “Are you expecting to be paid more money for your trouble? You’re not getting a penny farthing, for I’m sure that solicitor paid you handsomely for your duties.”

“He did, thankee.” Robert’s voice was polite. A crash of wind took the door when he opened it to leave and slammed it shut behind him.

Never in my sixteen years had I felt so desolate. And so alone.

I listened to hear the carriage roll away, but I could hear nothing save the whip of the wind in the chimney, the force of it beating against the outside walls. And the crash of the sea.

“So. You’ve arrived,” my uncle Caleb said, and I looked at him properly for the first time.

He was tall, too, and straight, clean-shaven. His eyes were dark and close set and his dun-colored hair was tied back with a frayed ribbon. There was something about his ears that drew my eyes, though I tried not to stare. They were badly formed, protruding from his head and covered with white scabs, like small hard pearls.

He gave me a smile that had no warmth in it. “You see a resemblance to Duncan?” he asked. “Your late father?”

“No,” I whispered, unable to speak more.

“People did say we looked alike when we were bairns, but as you know, he was the elder by a year. We were close in age. But not, I fear, in disposition.”

My aunt Minnie gave a snort. My attention swiveled to her and then back to my uncle.

“And then there were these.” My uncle paid no mind to her. He raised both hands to cup his ears as if he were hard of hearing. “A strange skin condition that afflicted me at an early age. I venture to say it ruined my life. There is no cure. Stare at them if you want. You must take me as you find me.”

“Of course.” I tried to smile. No point in saying I hadn’t noticed. A person would have to be blind or in the dark not to see what was there.

“Take off your cloak and bonnet, then,” my aunt Minnie said. “I’ve made a stew.” Her words were strong and deep, with a coarseness to them that one would not expect from a woman.

I laid my heavy cloak and my bonnet on a high-backed chair.

My uncle indicated a table that almost filled the entire living space. It was oaken, carved at the edges with a design of leaves and fruits, the thick legs ending in clawed feet. It was set with wooden bowls and spoons that shone like silver.

“Be quick with the victuals, Minnie,” he called. “The lass is hungry.”

“Thank you,” I said politely. “There is no need for haste on my account. The coach driver and I ate at the inn before we made this last leg of the journey. But the stew does smell delicious,” I added.

“It’s ready,” my aunt Minnie said.

An oil lamp swung from a hook on the ceiling, and it and the open fire cast light in the room. I saw a fiddle, gleaming chestnut brown on a stool by the fire. My aunt came to the table, took the bowls, and carried them to the hearth. I watched her lift the big iron pot from its swinging arm, set it down, and ladle stew into each bowl. She moved lithely, competently. Before she sat, she took off her pinafore, and I saw that she wore a heavy dark jumper with a faded red ship’s wheel on the front of it. And . . . men’s rough trousers. I’d never imagined to see a woman in trousers but then I’d never been in the company of a woman like my aunt Minnie before.