Forbidden Fruit (25 page)

Authors: Annie Murphy,Peter de Rosa

I said, “They’re assuming we’re lovers and they’re giving us a chance to get out.”

“The fecking car won’t budge.”

“Try again,” I said, with my usual squealy laugh.

Tugging his red tights half up, he looked in his mirror and saw me naked from the top up. “For cripesakes, Annie, get your

clothes on and come sit in the front with me.”

I was so jittery I could not button up my blouse.

“Can’t you do anything right?” he said.

“Maybe you should sit in the back and let me drive.”

“You don’t have an Irish license, eejit.”

“Don’t you call me that.”

“Shut up, and get dressed, I’ve got to think.”

“I can show the police your license.”

Now he got really mad at me. “How would you get by with my license?”

“I could tell them I was a transvestite. That’s what you look like in those tights.”

“Oh, I could die right now.” He sighed. “God, take me, I do not want to live.”

“Okay, sit in the back,” I repeated, scared because his pulse rate was far too fast at times. “I’ll cover you with a blanket

like they do in the movies.”

“Grand, except I don’t have a blanket and, besides, ‘tis not fitting for a bishop to do so.”

Eamonn had acted like a naughty boy and was getting a taste of his own medicine. This man who made Catholics tremble before

him was himself trembling because of the cops. He was a member of the hierarchy who intruded mercilessly into the sex lives

of others. Maybe a police inquiry into what a bishop did at night in a gravel pit might do them all good.

“Eamonn,” I said sharply, “they’re coming again.”

“Oh God, dear God, oh my God.”

I started to laugh because the situation was so earthy and so true. I contrasted Eamonn in his episcopal finery with the half-naked

man next to me struggling to zip up his fly and button his shirt after making fumbling love in a gravel pit.

The puncturing of pretensions, not only his but of all humankind, made me laugh some more. And laughter healed me. And, in

spite of his fears, he joined in and it healed us both because we were always able to laugh together. Nothing was too solemn

or too sacred but that laughter would not make it holier and more dear. My God was a God who laughed everything into existence;

and no single thing would cease existing while it still had in it the slightest capacity to make us laugh.

The Garda car passed us again. “Eamonn,” I said, shakily, “you don’t think they’re waiting for a backup team and a paddy wagon?”

His hands went futilely up-up-up in the air. “The driving license,” he moaned, “the registration number of the car, everything

is in my name. We might as well both sit here bald naked and let the Guards come take us to the Four Courts for trial.”

“Get out,” I said; and pointing, “Put those notebooks under the back wheel to give us leverage.”

“I cannot,” he said, climbing out of the car barefoot and immediately groaning because of the splashing from cold mud. “They

are official papers from my last EEC meeting.”

I scrambled into the driving seat. “Then”—I grabbed his coat—“it’ll have to be this.”

“No, Annie, that’s from Harrods and it’s got my name stitched into it. You don’t need your clothes, do you?”

I hugged myself tight. “Never,” I said. “Either your trench coat or jail.”

He grudgingly stuffed his precious coat behind the back wheels and I started the engine. At the first attempt, I lurched forward

out of the mud. After grabbing his coat, he ran after me, screaming, “For God’s sake, Annie, come back.”

I slowed down to let him catch up to me but stayed behind the wheel. “I’m thinking of leaving you here,” I said. “It’s about

time you faced the world without your clerical camouflage.”

“But, Annie,” he whimpered, “you wouldn’t do that. You

love

me. Here I am in a gravel pit with the cops waiting to pounce and my poor long johns are soaked to the knees.”

I looked him up and down. Finally: “Okay, hop in.”

Fortunately, we did not meet the cops.

“That,” he sighed, “was the worst experience of my life.”

“Blame it on me, Eamonn.”

I could tell he already had.

Next morning, Bridget called me.

“Well, well, Murphy, fancy that. I was wondering how that Bishop treated you in Inch.”

“Quiet,” I hissed. “My father’s next door.”

“After all, the clergy are all sex-mad, as anyone in the hotel trade knows. How’d you make out with your chauffeur?”

“We had a quiet dinner to discuss my mother’s drinking problem.”

“Dinner, my eye. I was only poked by a poor old security guard, but you, Murphy, have been —”

I crashed the phone down.

In addition to my sister Mary, now Bridget knew, and Bridget lived in Ireland, had an Irish boyfriend, and drank heavily.

But it was when I myself got drunk that I spilled the beans. This was two weeks later. Bridget blackmailed me into it by telling

me, truly or not, that I was to blame for the morning sickness she was experiencing.

The night after that, the most momentous thing in my whole life occurred.

In spite of our skirmish with the police, Eamonn still took his chances in the gravel pit. He was simply more careful to park

his car on firmer ground. He also brought a piece of wood in the trunk in case he needed it to get out of the mud.

Why wood? Maybe it reminded him of salvation by the wood of the cross. I told him an old sack or a piece of carpet was better.

We had no sooner reached our destination than I saw another car parked in the shadows. “Do you think the cops are waiting

for us?” I whispered.

“That car is not marked.”

“Undercover agents?”

The couple in the other car must have had their suspicions about us because they drove away on squealing tires.

It was the very end of October, a near-full moon was in the sky. My parents were about to leave Ireland, which meant this

was probably our good-bye to the gravel pit.

I felt in my abdomen a kind of pain that was for me the sign of ovulation. I told him frankly, “Tonight is the

night

.”

“Don’t spoil it, Annie, please.”

I smothered his warnings with kisses. That time, I insisted on being on top in the reclining front seat of the car. Had he

struggled, my weight, in that confined space, would have made it impossible for him to throw me off. I wanted no spark of

lust. This was to be love and only love.

Almost the grimmest place in Ireland was transformed for me that night. It was as when a perfect rose rises out of a dung

heap. There was no romance in the setting, only and entirely love. This was romantic because love was reduced to its essence:

two people who cared for each other and wanted only to express their love.

It struck me what we did had been done in far uglier places, in hovels, prisons, and refugee camps, among Jews in cattle trucks

taking them to Auschwitz. It is an expression of richness in poverty, proof that love can conquer everything.

The car in which my child was conceived was our little church. Whether people make love on grass in the open air, in the bed

of a bishop’s palace, or on the floor of a hovel, whether to a background of surf, sea, and wind, or of noisy automobiles,

there

for them is their holy place. Inside me, whatever Eamonn might say, was his true place of worship, more splendid, more worthy

than any cathedral built by hands.

Yet we were so ordinary. Not anarchists, not immensely wicked. Only because of circumstances were we subjects of what many

would consider a sordid little drama that might easily end in tragedy. All this subterfuge and pain because society makes

complicated rules and insists that God’s reputation depends on us keeping them. Because society will not allow ordinary people

like us to behave in the most ordinary of ways.

That night, unusually for me, I was very verbal, rapturously so. I wove a spell of words around him. I told him all that he

meant to me, all that he had done for me. “My time here has been magical,” I said, “and I’ll never again meet anyone like

you.”

I wanted him to know that I would never have the slightest regret for whatever happened to me. I told him I loved him now

and forever.

And when he said he loved me and came inside me I felt utter gladness and serenity, as if life itself were flowing inside

me. In that mutual profession of love, I knew that in my body we were two, my child and I.

This was one of those strange psychic moments when you know with certainty what cannot possibly be known. And from this point

on, from a deed done in love in the harsh surroundings of a gravel pit, my entire life was about to change forever.

Twenty-Six

M

Y PARENTS PREPARED TO FLY HOME. Daddy found Dublin an extended village with little to distract him from the raw, insinuating

presence of Wishie.

Then there was the yellow smear of autumn, too many days when the sun did no sightseeing, the intense cold and early dark

reminding him of death. He had forgotten how soon winter comes to Ireland and how bone-rotting the damp, once September days

had passed. Above all, he missed the glitz and frenzy of New York.

The morning my parents left, Daddy said, “It’s good to see you so settled. I told you Eamonn would heal you.”

“How’d he do it?” Mom said. “That’s what I want to know.” “You can’t stay here forever,” Daddy said at the airport. “But whenever

you come home, Annie, I’ll be there.”

Eamonn called to check that my parents had left. Our talk turned to money. I told him that Bridget wanted to share the apartment

with me and neither of us earned a lot.

“I have quite a small income myself, Annie, and everything else is on credit card.”

“Money,” I said, “could be the least of your worries.”

“You mean I might become a different type of father?”

“Don’t let’s celebrate too soon,” I said.

I sensed that this man who so often prided himself on being lucky—never so far an accident in driving or in having sex with

me—was becoming resigned to the inevitable.

No matter. He was a cork on the ocean, afloat and upright even in a storm. He lived only for the moment, regardless of consequences.

Which is why he made a good lover. But if and when it was confirmed that I was carrying his child, would he come away with

me or discard me for good?

In my heart, I knew the answer already.

I had worked overtime at the Burlington. On the Friday after my parents’ departure, I was free to stay with Eamonn at Inch

until Sunday night.

On the train that afternoon, I saw little of the countryside because in early November it soon gets dark. But I began the

habit of talking to my baby. “I love you,” I kept saying. “I love your father and I love you and I swear to God I’ll never

be separated from you.”

At Killarney, Eamonn was waiting for me in his Mercedes. He was very pleased to see me, but I noticed an almost forlorn look

in his wide-open eyes. “I missed you,” he whispered. “So good to have you back.”

“And away from the gravel pit.”

A wild dark night, and his driving had not changed. Inside the front door he started kissing me. Good, Mary was absent.

His hands were in my hair, on my breasts, up my dress. Locked together, we lurched down the hallway with him undressing me

with trembling fingers and removing his jacket and muttering, “This thing, this thing,” as though something alien had him

in its grip.

1 was sad for him, for his lack of control, and at the same time overwhelmed by his sweetness and innocence.

“I can’t make it to the bed,” he gasped, pulling me down on my hands and knees.

“Please,” I said, “not here.” I spoke out of pity for him.

He stretched me backward on the floor at the entrance to his room. Above me was the first Station of the Cross: Jesus Is Condemned

to Death. That upset me because the chief thing I loved about the Catholic religion was Jesus, a good Man, going to an undeserved

death. I imagined the look of bewilderment on His face as it dawned on Him that people were bad enough to want Him dead when

He only came to help.

On Eamonn’s face was the same look, of vulnerability, of someone condemned for something he did not understand; but this was

allied to such deep want in him that I felt I had never loved him more. Self-sacrifice had made him deny his real self. What

I saw, as I lay under the first Station of the Cross, was the real Eamonn hidden too long under all the sham desire to live

like an angel.

“Let’s go to bed,” I said. “This floor’s too much like the gravel pit.”

For him, the bed was a mile away. I held him and stroked him as he quivered and quaked against me. Afterward, we lay completely still, warmed by each other, mindlessly one.

In a kind of pained dream-like soliloquy, he said, “Wild, wild, wild, hungry, to give and receive so much, to be aware of

loneliness, to be so needy, to feel such warmTh, to be so… afraid.”

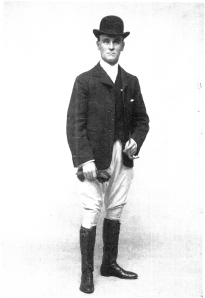

Grandfather Humphry Murphy, c. 1890, stole Annie’s grandmother’s heart.