Forbidden History: Prehistoric Technologies, Extraterrestrial Intervention, and the Suppressed Origins of Civilization (16 page)

Authors: J. Douglas Kenyon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Fringe Science, #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #Ancient Aliens, #History

Were modern humanity not so disordered in life, out of touch with nature, and imbalanced as well, gaining pharaonic insights would still be difficult. But we have developed the “cult of convenience” to a high order and live by another modern principle, that of “something for nothing.” Inasmuch as, in the spiritual realm, payment is a principle, such a worldview further amplifies the impediments toward pharaonic mentality.

Those who have seen, generally, the hollowness of modern thought must be at pains to discover its effects in themselves, so invidious is its process. The need to be surrounded by people, sound, activity, even noise, arises in the psychological consciousness of the cerebral intelligence, which subsists on stimulation. Says Schwaller de Lubicz, most modern people (as of the 1950s) could not have “stood” the serenity that prevailed in ancient Egypt.

Schwaller de Lubicz tells us that, in order to grasp the essence of the Anthropocosmic teaching, we need to reestablish in our minds a proper notion of the term

symbol

. A symbol is not merely “any letter or image that is substituted for the development of an idea.” Instead, a symbol is “a summarizing representation, which is commonly called a synthesis.” This process “feels” like something, often exhilaration.

The ancients selected these symbols knowing virtually everything about the natural counterpart (the correspondent) from gestation to its death. Mental caution is necessary, however, and the tendency to “fix,” by definition, the essence of the symbolic representation must be avoided. The qualities of a symbol are many and varied and not to be linguistically rigidified any more than molten lava. The symbol is alive, vital, and dynamic, because Anthropocosmic doctrine is a vitalist philosophy.

“To explain the Symbol is to kill it . . .” and, indeed, the landscape of academic Egyptology is everywhere strewn with the carcasses of dead, unheard symbols. “Rational thinkers” believe we’ve passed beyond simplistic thinking. Rather, in the last two millennia, we have fallen into it.

Many concepts of modern thought are defined and understood differently in

The Temple of Man—s

o many, in fact, that scientists, academics, and people generally, having unconsciously espoused a mechanical rationalism, will be

forced

to reject these ideas out of hand. “Cause and effect are not separated by any time.” There exists a “principle of the (present moment), mystical in character, that modern science ignores,” says Schwaller de Lubicz.

These and other similar statements cannot be reconciled with the current and opposing worldview. But one may examine the modern socio-scientific-technological state of the world in light of these ideas and, from so doing, draw tentative conclusions concerning the relative merit of the ancients’ teachings.

The history of science demonstrates that we seldom build upon the great discoveries of preceding generations of scientists. Few physicists today know Kepler’s laws of planetary motion; even fewer mathematicians appreciate that his unconventional use of the fractional notation of powers (e.g., X2/3 power) and the unique position he accorded the number 5 (which led to this) were a part of pharaonic mathematics thousands of years earlier. Modern science is as “pouring from the empty into the void,” to quote Gurdjieff. Modern science, Schwaller de Lubicz says, is founded upon incorrect premises. We know

kinetic

energy, not

vital

energy, and we tamper with forces, powers, and processes we do not and cannot now understand: We

are

the Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

Cerebral intelligence is based upon the sensory information conveyed to it by the major sensory systems. These are understood by the ancients in terms of both their natural, exoteric function (to provide the brain with information) and their esoteric, spiritual function. One cannot but be amazed, again, at the subtlety of the insights they conveyed. For example, “the faculty of discernment, located in the olfactory bulb, is the seat of judgment in man . . .”

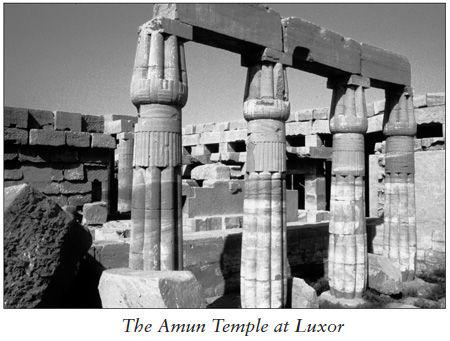

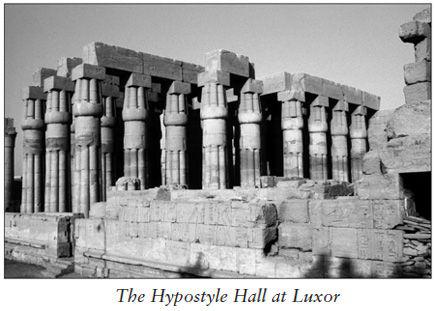

Well, the olfactory bulb is a so-called primitive structure of the brain with no direct connections to the cortex, the “advanced” gray matter. Nevertheless, apparently in deference to its unique anatomical characteristics, the ancients accorded olfaction one of the three secret sanctuaries in the head of the Luxor temple, Room V.

The moral sense, sexuality, and the physiological distribution of vital energy are combined in the relevant symbol, the cobra. Here in Room V of the temple is located “conscience.” Goodness has a spiritual fragrance (a fact noted by Swedenborg, who mentioned that the ancient Egyptians were the

last

to fully understand the science of correspondences).

Subtlety is all the more difficult to acknowledge and recognize when what is taught conflicts diametrically with what people already believe. Ironically, we seldom have evidence that appears to contradict the ancients’ teachings, which typically go beyond our accepted facts.

Schwaller de Lubicz includes a lengthy discussion of the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus. This papyrus (from Luxor in 1862) was translated after 1920 by the renowned Egyptologist J. H. Breasted. The effort convinced him of the elevated status of ancient Egyptian science and mathematics (as it did others) but apparently modern Egyptologists remain uninfluenced by his writing. An extensive anatomical dictionary of the skull, head, and throat (also in hieroglyphics) enables the reader to comprehend the many cases of head injury described in the papyrus. Despite the ancients’ lack of a really good source of head injury cases (e.g., automobile accidents), their knowledge of clinical neuroanatomy was detailed and correct, without the benefit of EEGs, CAT scans, and magnetic resonance imaging.

The ancients described a human as comprising three interdependent beings, each having its own body and organs. Of course, all were essential and important. However, the head was especially so, for it was the seat of the spiritual being. There, the blood was spiritualized, infused with vital energy prior to coursing through the corporeal and sexual bodies. These bodies, vivified by the spiritual being, live a lifetime without knowing it in a state of ignorance or self-delusion.

Modern humanity has struck an iceberg of its own making. Those forces we have tampered with and let loose, but which we do not understand, threaten our annihilation. We have a role in cosmic metabolism but are unable to fulfill it. We must cease fiddling while our planet burns, cease occupying ourselves with liposuction, with killing birds to kill insects, with poisoning the soil to kill weeds, with polluting air and water. Any sane person can see our way of “life” has become unnatural, a condition the ancients foresaw.

Everyone’s consciousness needs to expand, to evolve: We need to become aware of a great deal that, right now, escapes us. This can occur by choice— the price is some suffering. “And now that the temple of Luxor has shown us the way to follow, let us begin to explore the deeper meaning of the teaching of the pharaonic sages,” wrote Schwaller de Lubicz. We shall discover along the way what a trivial price we are asked to pay.

14

Fingerprinting the Gods

A Bestselling Author Is Making a Convincing Case for a Great but Officially Forgotten Civilization

J. Douglas Kenyon

A

lthough few people would question the popularity of the movie

Raiders of the Lost Ark,

no academic worth his salt ever dared to say the movie was more than a Hollywood fantasy, either. So when the respected British author Graham Hancock announced to the world in 1992 that he had actually tracked the legendary Ark of the Covenant of Old Testament fame to a modern-day resting place in Ethiopia, serious eyebrows everywhere twitched upward. Nevertheless, objective readers of his monumental volume

The Sign and the Seal

on both sides of the Atlantic soon realized that Hancock’s case, incredible though it seemed, was not to be easily dismissed. The exhaustively researched work went on to enjoy widespread critical acclaim and to become a best seller in both America and the United Kingdom as well as the subject of several television specials.

Hancock’s writing and journalistic skills had been honed during stints as a war correspondent in Africa for

The Economist

and

The London Sunday Times

. Winner of an honorable mention for the H. L. Mencken Award (

The Lords of Poverty,

1990), he also authored

African Ark: Peoples of the Horn,

and

Ethiopia: The Challenge of Hunger

. In

The Sign and the Seal

, Hancock was credited by

The Guardian

with having “invented a new genre—an intellectual whodunit by a do-it-yourself sleuth . . .”

Apparently, though, the success of

The Sign and the Seal

only whetted the writer’s appetite for establishment chagrin. His subsequent book,

Fingerprints of the Gods: The Evidence of Earth’s Lost Civilization,

sought nothing less than to overthrow the cherished doctrine taught in classrooms worldwide, that civilization was born roughly five thousand years ago.

Anything earlier, we have been told, was strictly primitive. In one of the most comprehensive efforts on the subject ever—more than six hundred pages of meticulous research—Hancock presents breakthrough evidence of a forgotten epoch in human history that preceded, by thousands of years, the presently acknowledged cradles of civilization in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Far East. Moreover, he argues, this same lost culture was not only highly advanced but also technologically proficient, and was destroyed more than 12,000 years ago by the global cataclysm that brought the ice age to its sudden and dramatic conclusion.

Kirkus Reviews

called

Fingerprints of the Gods

“a fancy piece of historical sleuthing—breathless but intriguing, and entertaining and sturdy enough to give a long pause for thought.”

Graham Hancock discussed

Finger

prints of the Gods

with

Atlantis Rising,

wherein he indicated that the book was enjoying the kind of favorable media attention that helped to make

The Sign and the Seal

an American hit. Interviewers, Hancock felt, were generally positive and open to his ideas. Though the reception among academics had been something less than cordial, that was to be expected.

“One of the reasons the book is so long,” he explained, “is that I’ve really tried to document everything very thoroughly so that the academics have to deal with the evidence rather than me as an individual, or with what—they like to think—are rather vague, wishy-washy ideas. I’ve tried to nail it all down to hard fact as far as possible.”

Nailing down the facts took Hancock on a worldwide odyssey that included stops in Peru, Mexico, and Egypt. Among the many intriguing mysteries that the author was determined to investigate fully were:

- Ancient maps showing precise knowledge of the actual coastline of Antarctica, notwithstanding the fact that the location has been buried under thousands of feet of ice for many millennia.

- Stone-building technology—beyond our present capacity to duplicate—in Central and South America, as well as Egypt.

- Sophisticated archaeoastronomical alignments at ancient sites all over the world.

- Evidence of comprehensive ancient knowledge of the 25,776-year precession of the equinoxes (unmistakably encoded into ancient mythology and building sites, even though the phenomenon would have taken, at a minimum, many generations of systematic observation to detect, and which conventional scholarship tells us was not discovered until the Greek philosopher Hipparchus in about 150

B.C.E.

). - Water erosion of the Great Sphinx dating it to before the coming of desert conditions to the Giza plateau (as researched by the American scholar John Anthony West and the geologist Robert M. Schoch, Ph.D.).

- Evidence that the monuments of the Giza plateau were built in alignment with the belt of Orion at circa 10,500

B.C.E.

(as demonstrated by the Belgian engineer Robert Bauval).

Unfettered as he is by the constraints under which many so-called specialists operate, Hancock sees himself uniquely qualified to undertake such a far-reaching study. “One of the problems with academics, and particularly academic historians,” he says, “is they have a very narrow focus. And as a result, they are very myopic.”

Hancock is downright contemptuous of organized Egyptology, which he places in the particularly short-sighted category. “There’s a rigid paradigm of Egyptian history,” he complains, “that seems to function as a kind of filter on knowledge and which stops Egyptologists, as a profession, from being even the remotest bit open to any other possibilities at all.” In Hancock’s view, Egyptologists tend to behave like priests in a very narrow religion, dogmatically and irrationally, if not superstitiously. “A few hundred years ago they would have burned people like me and John West at the stake,” he says, laughing.

Such illogical zealotry, Hancock fears, stands in the way of the public’s right to know about what could be one of the most significant discoveries ever made in the Great Pyramid. In 1993, the German inventor Rudolph Gantenbrink sent a robot with a television camera up a narrow shaft from the Queen’s Chamber and discovered what appeared to be a door with iron handles. That door, Hancock suspects, might lead to the legendary Hall of Records of the ancient Egyptians. But whatever is behind it, he feels it must be properly investigated.

So far, though, there has been no official action, at least not a public one. Citing episodes personally witnessed, he protests, “You have Egyptologists saying ‘There is no point in looking to see if there’s anything behind that slab’—they call it a slab, they won’t call it a door—‘because we know there’s not another chamber inside the Great Pyramid.’” The attitude infuriates Hancock: “I wonder how they know that about this six-million-ton monument that has room for three thousand chambers the same size as the King’s Chamber. How do they have the temerity and the nerve to suggest that there’s no point in looking?”

The tantalizing promise of that door has led Hancock to speculate that the builders may have purposely arranged things to require technology of ultimate explorers. “Nobody could get in there unless he had a certain level of technology,” he says. And he points out that even one hundred years ago, we didn’t have the means to do it. In the last twenty years the technology has been developed and now the shaft has been explored, “and lo and behold, at the end is a door with handles. It’s like an invitation—an invitation to come on in and look inside when you’re ready.”

Hancock is far from sanguine about official intentions: “If that door ever does get open, probably there will be no public access at all to what happens.” He would like to see an international team present, but suspects that instead “what we’re going to get is a narrow, elite group of Egyptologists who will strictly control information about what happens.” In fact, he thinks it’s possible that they’ve even been in there already. The Queen’s Chamber was suspiciously closed for more than nine months after Gantenbrink made his discovery.

“The story was given out that they were cleaning the graffiti off the walls, but the graffiti were never cleaned off. I wonder what they were doing in there for those nine months. There’s what really makes me angry, that this narrow group of scholars control knowledge of what is, at the end of the day, the legacy of the whole of mankind.”

Gantenbrink’s door is not the only beckoning portal on the Giza plateau. Hancock is equally interested in the chamber that John Anthony West and Robert M. Schoch, Ph.D., in the course of investigating the weathering of the Sphinx, detected by seismic methods, beneath the Sphinx’s paws. Either location might prove to be the site of the “Hall of Records.” In both cases, the authorities have resisted all efforts at further investigation.

Hancock believes the entire Giza site was constructed after the crust of the earth had stabilized following a 30-degree crustal displacement that destroyed most of the high civilization then standing. According to Rand and Rose Flem-Ath’s

When the Sky Fell: In Search of Atlantis,

upon which Hancock relies, that displacement had moved an entire continent from temperate zones to the South Pole, where it was soon buried under mountains of ice. This, he believes, is the real story of the end of Plato’s Atlantis, but the “A” word is not mentioned until very late in his book. “I see no point in giving a hostile establishment a stick to beat me with,” he says. “It’s purely a matter of tactics.”

The Giza complex was built, Hancock speculates, as part of an effort to remap and reorient civilization. For that reason he believes the 10,500

B.C.E.

date (demonstrated by Bauval) to be especially important. “The pyramids are a part of saying this is where it stopped. That’s why the perfectment, for example, to due north, of the Great Pyramid is extremely interesting, because they obviously would have had a

new

north at that time.”

Despite a determination to stick with the hard evidence, Hancock is not uncomfortable with the knowledge that his work is serving to corroborate the claims of many intuitives and mystics. On the contrary, he believes that “the [clairvoyant ability] of human beings is another one of those latent faculties that modern rational science simply refuses to recognize. I think we’re a much more mysterious species than we give ourselves credit for. Our whole cultural conditioning is to deny those elements of intuition and mystery in ourselves. But all the indications are that these are, in fact, vital faculties in human beings, and I suspect that the civilization that was destroyed, although technologically advanced, was much more spiritually advanced than we are today.”

Such knowledge, he believes, is part of the legacy of the ancients that we must strive to recover. “What comes across again and again,”he says, “particularly from documents like the ancient Egyptian pyramid texts, which I see as containing the legacy of knowledge and ideas from this lost civilization, is a kind of science of immortality—a quest for the immortality of the soul, a feeling that immortality may not be guaranteed to all and everybody simply by being born. It may be something that has to be worked for, something that results from the focused power of the mind.” The real purpose of the pyramids, he suggests, may be to teach us how to achieve immortality. But before we can understand, we must recover from the ancient amnesia.