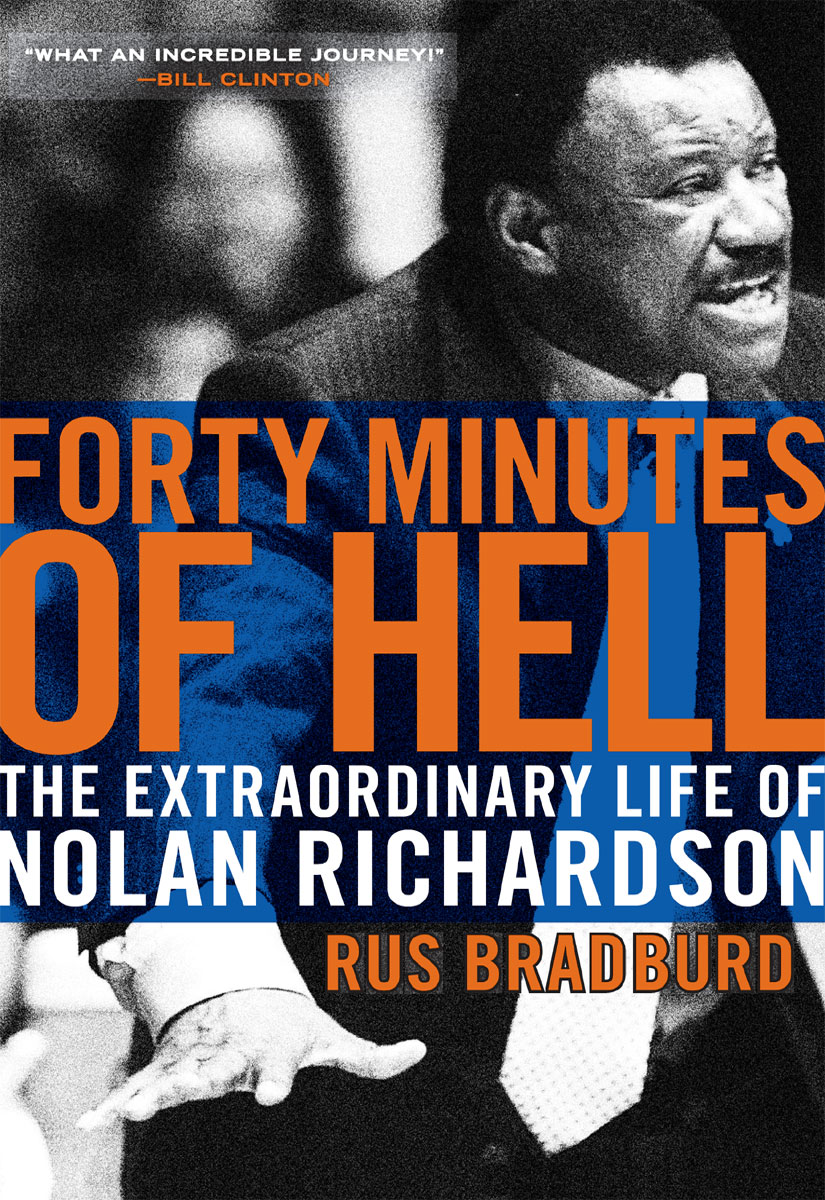

Forty Minutes of Hell

Read Forty Minutes of Hell Online

Authors: Rus Bradburd

The Extraordinary Life of Nolan Richardson

For Bobby Joe Hill and Ricky Cardenas

For Bob Walters and Darrell Brown

For Alma Bradburd and Yvonne Richardson

Prologue:

Soul on Ice

A Bewitched Crossroad

Black Boy

The Known World

Native Son

Nobody Knows My Name

Going to the Territory

The Souls of Black Folk

God's Trombones

Invisible Man

The Edge of Campus

Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone

The Fire Next Time

Blues for Mister Charlie

Soledad Brother

Go Up for Glory

If Blessing Comes

Only Twice I've Wished for Heaven

Shadow and Act

Things Fall Apart

Makes Me Wanna Holler

Battle Royal

Your Blues Ain't Like Mine

Brothers and Keepers

Another Country

Go Tell It on the Mountain

SOUL ON ICE

M

y great-great-grandfather came

over on the ship,” Nolan

Richardson said. “I did not come over on that ship. So I expect to be treated a little bit different.”

With television cameras and tape recorders rolling, Richardson began giving the people of Arkansas and America a history lesson, although his purpose was not entirely clear. This was supposed to be another ordinary press conferenceâthat's what most journalists had expectedâand a briefing on an upcoming game was the norm. Reporters arrived Monday afternoon, February 25, 2002, figuring that Richardson might still be discouraged after Saturday's loss at Kentucky. Richardson had said that night: “If they go ahead and pay me my money, they can take the job tomorrow.” Since then, there had been whispers that perhaps the coach was getting ready to retire.

That would have been big news for Razorback basketball fans. Richardson had coached Arkansas to the landmark 1994 NCAA championship. With nearly four hundred wins at Arkansas, he had

earned two additional Final Four appearances, led Arkansas to thirteen NCAA Tournaments, and could brag of one of the highest winning percentages in college hoops in the 1990s. Arguably the top black coach in America, Richardson was the first black coach in the old Confederacy at a mostly white university, as well as the first to win the national championship at a Southern school.

On this Monday, however, less than a decade removed from that national title, Richardson would become the kamikaze coach.

After seventeen seasons, he was still the only black coach in any sport at the University of Arkansas, and that bothered him. “I know for a fact that I do not play on the same level as the other coaches around this school play on,” he said. “I know that. You know it. And people of my color know that. And that angers me.” Richardson glanced toward the door, as if all twenty white head coaches of the other Arkansas Razorback sports were lined up outside.

The journalists scratched their heads in wonder, shifted in their seats. It was a bizarre session, they thought, but not a fatal one for Richardson. The media had heard him rant, privately, about their coverage of him and his program. That kind of complaining is common among college coaches, but on this occasion, the topic veered erratically from basketball.

It was clear that Richardson wanted to talk about race.

He surveyed the media room at the Bud Walton Arena, and pointed out that everyone except him was white. “When I look at all of you people in this room,” he said, “I see no one who looks like me, talks like me, or acts like me. Now why don't you recruit? Why don't the editors recruit like I'm recruiting?” The collection of media representatives swallowed hard or scribbled in their notebooks. Although he was not shouting, he used the righteous tone of an Old Testament prophet. Richardson was a bear of a manâ6'3" and, at the time, close to 230 poundsâas much a linebacker as a basketball coach. He stood alone on the podium, wearing a flaming-red Arkansas pullover, and the banner behind would frame him in the same color for television viewers.

On that day, Richardson's Arkansas Razorbacks were 13-13 overallânot the kind of season that normally could be called a disaster. Richardson said as much. “I've earned the right to have the kind of season I'm having.” That was likely true. However, it was Richardson's worst stretch since he took the job in Fayetteville. Arkansas was 5-9 in the Southeastern Conference and had lost nine of their past twelve games.

It would be difficult to exaggerate Richardson's cachet at the school, but the coach seemed to do just that, essentially claiming the reason recruitsâbasketball and footballâcame to Arkansas was because of him. “The number one thing that's talked [about] in our deal is the fact that the greatest thing going for the University of Arkansas is Nolan Richardson.”

Richardson had kept his program, practices, and locker room open to every reporter, but not anymore. “Do not call me ever on my phone, none of you, at my home ever again,” he added. “Those lines are no longer open for communications with me.”

Richardson must have believed his job was on the line, and yet it seemed as though he both wanted and did not want to remain at Arkansas. He made it clear he would not walk away; that wasn't what he'd meant two days earlier in Kentucky. “I've dealt with it for seventeen years,” he said, “and I'll deal with it for seventeen more. Because that's my makeup. Where would I go?”

Nobody in the media had suggested he should be terminated, but Richardson accused them of it anyway. “So maybe that's what you want,” he said. “Because you know what? Ol' granny told me, âNobody runs you anywhere, Nolan.' I know that. See, my great-great-grandfather came over here on the ship. I didn't, and I don't think you understand what I'm saying.”

Then Richardson wheeled, confronted the cameras, and ended the speech by saying, “You can run that on every TV show in America.”

A question-and-answer session followed. No journalists asked questions about race, or ships, or his grandmother. The first query: Had he watched the tape of the Kentucky game?

“I thought it would blow over,” one veteran Arkansas journalist says. “No way did I think Nolan was going to get fired. Sure, he bristled, but mostly it was surreal, bizarre.”

It might have blown over but the highlights, if you can call them that, were indeed run on television shows across the country. The quotes most often broadcast were the most confusing. Why was Richardson referring to his grandmother? And what ships? He must have meant slave ships.

The highlights ran again and again.

The story grew legs: a rich and famous black man was lecturing a roomful of white media about race, reminding Arkansas, and then America, about its racist past.

Several subsequent newspaper and online accounts emphasized how obsessed Richardson had been with race throughout his career.

Sports Illustrated

called the press conference “â¦a bewildering self-immolation.”

The endless cycling of the clips brought national attention to the most perplexing forty minutes in college basketball history. How could a black man who was so prosperous come across as so ungrateful?

Â

Of all the basketball coaches

who have won national championships, none had the deck stacked against him like Nolan Richardson. He grew up in the poorest neighborhood in America's most remote city; not one black man was working the sidelines in major college basketball when he began coaching high school in 1967.

Richardson was an innovator whose teams performed at a frantic and furious pace. His style of play was nicknamed “Forty Minutes of Hell.”

Facing a Richardson team was physically and psychologically exhausting. He recruited players who were overlooked and had plenty to prove; then he conditioned them with a regimen of near-brutality until they were as hard and sharp as swords. During breaks in practice,

between workouts, before games and at halftime, his speeches made it clear to his team that no one in the basketball hierarchy respected himâor any of themâand the only possible retribution for the snub had to be found on the basketball court. By game time they were so emotionally wired they seemed to give off sparks.

While most coaches separated their systems into offense and defense, Richardson saw the game as flowing turmoil. Substitutions came often, sometimes en masse, and the rapid rotation of players contributed to the sense that the game was descending into chaos.

His players exerted defensive pressure the entire length of the court, attacking the ball the instant it was passed into play and dogging the dribbler's every step. Traps came quickly and constantly, but rarely at a moment that could be anticipated.

If the opponent managed to split the trap or escape the press with a precise pass, the illusion of an advantage would present itself, and that momentary mirage could be their undoing because Richardson's team had badgered them into playing at a speed at which they were unaccustomed. Endurance became paramount as his platoons of substitutes weighed heavily on the backs of his opponents. His five players were locked in relentless pursuitâpursuit of the dribbler, pursuit of the pass, pursuit of the missed shot, pursuit of the coach's approval. The thronging defense further frustrated the opponent's attack when his players rotated quickly after the double-teams. If his men made a steal, it was often because a forgotten guard trailing the play refused to give up and tipped the ball from behind. They would overcome players ahead of them, overcome halftime disadvantages, overcome their (often imaginary) underdog status.

At times it appeared Richardson must have six players on the nightmarishly cramped court. After a missed shot or a steal, though, when they converted to their fast-breaking offense, the court instantly felt as wide open as a West Texas freeway.

Like his press, the half-court offense was unpredictable by design. His teams slashed, penetrated, and attacked the basket before the

opponent could establish their defense. A diagram of his system on a chalkboard looked like a Jackson Pollock painting.

Purists and traditionalists found “Forty Minutes of Hell” to be a violation of everything they'd learned about the sport. It was as if Richardson's teams wanted to destroy the very decorum of the game. And that was indeed precisely what his teams wantedâto confiscate the traditional etiquette of a college basketball game and snap its neck.

Richardson was an instinctive genius who disdained basketball's textbook theories, but he was rarely credited as a brilliant teacher, and this rekindled the resentment: when he was disrespected, his players were also implicated. The only way to shed the shackles and undo the affront was to play the next game as if their very existence depended on it. In this fashion, the paradigm was endlessly renewed.

How was it possible that this pioneering coach, winner of the national championship, whose style of play had altered the way college basketball was played, was going to be most remembered for a press conference?