Frannie in Pieces (10 page)

Authors: Delia Ephron

Simon shows up first, edging backward, instructing campers, “Make sure your foot is secure; give

yourself a second to get rooted before you take another step.” He breaks off a few branches to clear a wider path, tosses them, and steps off the trail to supervise before he spies me. “Hey there, big feet.”

My feet

are

big. Size nine and a half. Has he noticed, or is this simply one more of his many strange greetings? Regardless, my feet suddenly loom, large as swim fins. Besides, they're grimy. Grimy swim fins. Now I do not feel suave. I feel the opposite of suave. As Simon passes, heading south, he dusts the remains of some feather ferns off my shoulder. A startling move. As his hand reaches out, I slap my arms across my breasts, reacting as if he's going to grope me. And then what happens? An innocent dustingâhis hand whisks my shoulder and the green fluff flies off.

“While we were kicking butt, Frannie was having a snoozerooni,” he calls to the campers.

“She's here, we've found her,” Lark trumpets. “She was having a nap.”

“Hardly,” I maintain coldly. “I was scavenging for unusual ferns.”

The kids appear red cheeked and winded, but happy. There are lots of shrieks as the downward slope provides a momentum of its own. They all travel faster than they intend. Rocco, last in line, shows me a lizard he's stashed in his pocket. “See this lizard? It's not a lizard, it's a wizard.” As soon as he passes, Iâ¦well, I intend to bop right down the trail behind them, but I can't actually move. I want to. My brain is sending messages to my feetâat least it's tryingâbut my feet stay put. The trail looks so steep, so incredibly steep.

I grind my flip-flops into the dirt and try to inch along, but then I hit a protruding root. I can slide out of my flip-flops and step over, but the trail dips sharply right after.

Again I lose sight of the kids, although for a short while I hear squeals as they slip and slide down the slope.

Eventually I'll venture down. Eventually. Right

now I'll take another break. This scenery could be a bunch of jigsaw pieces put together. The trail, the fern bog, the forest of trees in summer bloom. The nearest trunk of a pine begins to fragmentâthat mossy bit would be a spot of green on an otherwise brown piece, the knot in the oak might appear as curvy lines of gray until two pieces fit together. My foot, digging into the earth for traction, breaks into interlocking jigsaw pieces, some of which have blue knobs where they overlap my jeans or a red stripe, the flip-flop thong. My arms splinter. I feel my head dividing, features fractureâone bit contains an eye and part of my nose, another some shading on my cheek. Humpty-Dumpty sat on a wall.

Don't look at the downward slope, that forbidding downward slope.

I'm going to die.

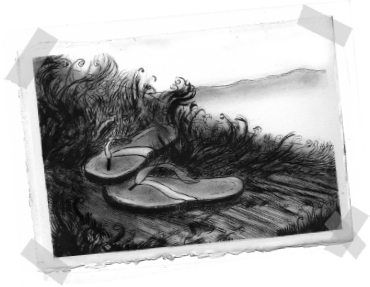

If I had to draw this, I'd draw two abandoned flip-flops. That suggests a story all right, and not a cheery one.

A big fat horsefly buzzes around. Horsefly bites swell and itch like crazy, but I won't wave it off. Almost any move might send me crashing, a stupendous tumble to the bottom. There I would end, one leg one way, one leg the other, startled and broken like Dad.

The crunch of pebbles and dry twigsâthat might signal the approach of a small hungry bear. The top of his head bobs into sight, the buzz cut so flat I could balance a glass on it, then Simon's face freshly coatedâa slab of white ointment on his nose and cheeks, even a stripe across his forehead. He's stripped off his shirtâthat's a shocker: a flaming

pink hairless chest, pulsing pecs. Do pecs actually pulse? I believe I detect throbbing, yes, that's my definite impression. His naked arms look positively sculpted and slick from sweat, and that starts me thinking about how I have big circles of sweat under my arms, I probably smell, and he's undoubtedly noticing.

“Go down on your butt,” he says.

I think about that. Trouble is, if I do, I have to sit, and it seems wiser to remain static.

Simon holds out his hand. I release the tree, grab his hand, wobble back and forth, but his grip steadies me, in fact I feel as if I'm being anchored by iron.

“Now sit down,” he orders.

I lower myself to the ground.

“And mooch along.”

“Mooch?”

“Mooch.” I swear I detect the tiniest twitch of his lips indicating that he might be holding a grin in check.

I try an MLS from this pathetic position with Simon the giant hovering above. A waste of energy. “You go ahead,” I tell him.

“I'll wait. No big deal.”

“Please go on.” I guess he hears hysteria in the high-pitched screech that I not too successfully suppress, because he acquiesces.

“You sure?”

“Yes.”

When he's out of sight, I begin the mooch, moving my feet first and then my hands, scooting my butt up last. I get good at it, descending faster and faster, even learn to keep my butt elevated so it doesn't get scraped. Just before I hit the home stretch, the path levels to a modest incline. I'm able to rejoin the campers walking. “Hi, there,” I call, relieved not to have been humiliated in front of them.

“Fanny came down on her frannie,” says Simon. “Let's give her a cheer.”

What a jerk.

Now Rocco is calling me Fanny every five seconds, like I really care, but it's so tedious and inevitable that an uncreative person like Simon would crack the oldest joke in the book, and, as a result, all the way home, Rocco is shouting, “Hey, Fanny, where's your butt?” until his sister nearly pulls his arm out of his socket and Mr. DeAngelo has to stop the bus and squeeze his ample body down the aisle to physically separate them.

Tonight, working the puzzle isn't calming. I'm

too wired. I gnaw red licorice vines while I hunt through the box for blue-and-white pieces. In the photo they appear to be a dinghy floating in the cove. Why would Simon slather sunblock over his face and then let his chest fry? Who cares what the answer to that is?

Boat bits, boat bits. Here's another. Aha, this fits together. What are these coral-and-gray pieces? I start another pile for them. I am surrounded by little heaps of puzzle pieces and a smorgasbord of tastiesâvines, peanuts, a bag of chocolate bits, a package of Velveeta. It's hazardous to stretch or shift positions or I'll knock one pile into another. I should have said something squelching to Simon. Something squelching likeâ¦I don't know, my mind is blank. Lobster. I could have called him lobster, you know, because of how red he is, all sunburned. Well, that would have been a pathetic retort. I'm always trying to relive the moment. What I should have said instead of what I did say, which, in this case, was nothing.

Oops, I pressed a piece of cheese into the puzzle.

I've assembled a blue-and-whiteâstriped rowboat and fragments of deep-blue sea where the puzzle pieces loop outside the boat's edge. In the photo the image seems flat, but when it's put together in the puzzle, I discern the curve of the hull, the shallow interior; I even sense buoyancy. Is there someone in the boat? I look closely. Is that smudge of color a person? Whoops. I slam my hands against the floor to steady myself. What happened?

Did the floor of my room tilt sideways?

No, impossible. I'm tipsy from exhaustion, my balance unstable from leaning over the puzzle, my brain scrambled from hours of scrutinizing the minute differences between colors and between shapes.

At the edge of the room, where carpet meets wall, the floor humps up, and this hump ripples toward and under me, and behind it another appears, and another. My stomach lurches as swells

in the carpet lift me up and down. Fear shuts my eyes, my tummy somersaults again and again. An instinct, I pat my hair. How bizarreâit's frizzing. I'm chilly. I need a sweater.

Open your eyes, Frannie. Sometimes, when I'm anxious, I order myself around. Like at Dr. Glazer's, when he's drilling. Breathe, you moron. So open those eyes, Frannie girl.

The first thing I see are my bare feet, instantly recognizable because of the chipped lilac toenail polish, in a shallow puddle of water, and stripes, blue and white. That's the floor, blue, white, shiny, and slick. My cold, naked feet are squeezed between a coil of thick, rough rope and a bundle of fishnet. What's this? I touch a piece of yellow rubber, pick it up. OhmyGod, Velveeta cheese. I don't know what to do, so I flick it over the side. Yes, I toss it overboard, understanding I'm in a boat before I've barely seen enough to know it.

I am the only passenger in this small dinghy, and I am seated on a bench, a wooden plank. The boat

bobs, and I bob along with it. An unpleasant tang disturbs my nose. Fish are here. Or else it's just sea flavors carried on a wind that stings my face and seals Dad's shirt to my body.

I'm not really in the ocean, though. Water slaps the sides of the boat as if there are tides and currents, but in fact I'm marooned in a pool of water. Each time the boat bobs up, I spy the weirdly shaped edge of the pool, stubby fingers of water jutting in and out. I'd recognize them anywhere: the knobby ins and outs of puzzle pieces. And beyond thatâ¦beyond my puzzle island there is no beyond. Around the water's edge, tightly clinging to every in and out, wraps a wall of white. Is it solid or vapor? Could it be void? Void: containing no matter. Empty.

I spot a pinpoint glow, a mini beacon of hope, boring through the white. Maybe out there isn't void, maybe that white is weather. It doesn't look or behave like weather. Even thick fog creeps, rises, and rolls, while this stuff merely

is

. I pray it's

weather, because otherwise I don't know how to comprehend my place. What world am I in? What space or time? Twisting around, I find no oars, but hooked onto the boat is a silent outboard engine. Is it dead or off, and does it matter? I can't reach the light anywayâit's beyond the water. What would happen if I motored this boat right off the puzzle? Would I collide with a wall, would I bounce off something soft and woolly, would I evaporate entirely the way my arm appeared to evaporate when I stuck it out the window?

The dot of light comforts from a distanceâwatching it is hypnotic, and besides, there's nothing else to do. Now, on either side of the yellow spot, there appears a green squiggle as if someone has squeezed paint right out of a tube. The green flattens and more colors appear, streaks of milky pink and red, flecks of black. It's all a murky mess and then it's not.

In tiny but precise relief, the yellow glow of a lamp burns inside a second-story window bordered with

green shutters. It's the puzzle window I tumbled into, the window of the ancient Irish house with its rose walls and tiled roof. Like the patch of ocean I'm bobbing in, the house has knobby in-and-out edges. Unmistakably they resemble the unconnected sides of jigsaw pieces.

The way this image revealed itself reminds me of what happened when Mom decided I might need glasses. I couldn't catch the ball at a Little League tryout, and she couldn't accept that I am no athlete. The problem had to be my vision. So she took me to the ophthalmologist, who made me look through gigantic binoculars attached to a big black metal machine. The doctor kept asking, “Can you tell me what that is?” “A fuzzy blob,” I answered. He spun some dials, and there they were, a wheel with spokes, a car, a rabbit, a mouse in a cage. Well, there's no doctor here spinning dials; there's only me and my eyeballs on the loose. Trust your eyes, they'll lead you where you need to go. Hope Dad was right about that.

Dad? Dad! I see him in the window. Is it him? From here, barely illuminated, barely more than a silhouette. He raises his arm. It is the way he always greeted me. Whenever I walked out the door at Mom's and he was waiting by the car, he would hold his hand up, flat, fingers spread. “Hey, I'm here, this way, Frannie.” As if I didn't know where I was going. As if I wasn't running right at him. Top speed.

“Dad! Dad!” I stand in the boat, raise both arms, and signal wildly. “Dad!”

A wave socks me right out of the boat. My back slaps the water. As I sink, water rushes into my nose and mouth, my shirt balloons.

Gagging and sputtering,

I'm on my back, rolling side to side on the floor of my room.

“Frannie, are you all right?”

I flip over, shove the puzzle board under the bed, and with my comforter I blanket what remainsâmy box, piles of sorted pieces. Mom whacks the door wide; it slams into one of the big cardboard boxes and comes right back at her.

“I'm⦔ I can't stop coughing. I have to bend over while she pats my back and I have a complete coughing fit, spitting up water.

“Good grief, what happened? You're all wet.”

My clothes are stuck to me, my hair plastered to my head. She's right. I am all wet.

“Why?”

Why?

“Why did you take a shower in your clothes? What's wrong with your foot?” Mom kneels down. “Give me a tissue, would you?” Mel hands one over, and she wipes my foot and examines some yellow goop. Am I excreting strange pus? She smells it. “Cheese?”

“Maybe. Velveeta.”

“You're eating in the shower? For God's sake, Frannie, you're shivering, where's your towel? Why did you take a shower in your clothes?” Her voice spikes shrill. She sprints into the bathroom, revealing, behind her, all of Mel in boxer shorts. Not a sight I ever wanted to see. “What are you doing up so late?” He cranks his head from side to side. Loud cracks are heard. Perhaps his knuckles are in his neck. “What time is it?”

My mom sweeps back in, wraps me in a giant towel, and keeps on ranting, “Taking a shower in her clothes. Eating cheese. What is she thinking?”

She. That's me.

“Take off your clothes.”

“I can't take them off with him here.”

I notice my hand. The Band-Aid hangs. Mom grabs my wrist and we both look closely. “What's wrong here?” she asks.

“Nothing. I had a splinter; it's gone.” It

is

gone. It must have been washed out by the water. “Mom, stop fussing.”

“What smells?” says Mel.

“I'm fine, I'm really fine.” I back them out. “I was painting at camp today, and showering seemed like an easy way to get the paint off my clothes and me at the same time.”

“I didn't notice paint on your clothes.”

“Why?”

Recognize my trick: Derail them with something nonresponsive. Mel gets a cloudy look, as if

he can't read the writing on the medieval walls, but Mom blasts on, “Why is your comforter on the floor?” That one last question remains as I shut the door, almost excising Mom's nose.

Why am I wet?

I drop the towel and peel off my clothes. Why am I wet? How could I be wet?

After wrapping myself up again, I sit on the bed.

Could I be having blackouts?

I heard about them in second grade from Maria. “He drank a fifth,” she said, swinging upside down on the jungle gym. “Dad had a blackout.” She raised her desktop and stashed her lunch inside. I came home and asked my mom. “What's a fifth? What's a blackout? Maria's dad has them.” Mom put it all together and told me what happens if you drink too much liquor. Could a person have a blackout without drinking at all and take a shower they don't remember? Or did I walk in my sleep during a dream and dunk myself?

I tuck the towel around me, scoop up my wet

duds, and carry them into the bathroom. I can't help noticing: The jeans and shirt are sopping, but the shower curtain and tub are dry. No way was I recently in there getting doused. I wring out the wet, squeezing hard, and hook the jeans over the shower spout. What smells? Mel was rightâsomething smells. I mash Dad's shirt to my face. Briny. I sniff the jeans. Briny. I sniff my arm. What smells? Me. I lick my arm. Salt. The water on me is salty. Grabbing a hank of hair, I pull it around. I taste it, smell it, feel it. My hair has been in the ocean. Ocean-wet hair is stiff. When I come home from the beach, my hair has the texture of wood.

I drape Dad's shirt over the tub, taking care to smooth the wet wrinkles before I acknowledge the reality: I was there. I brush my teeth with extra diligence, prolong the chore by doing stupid things like pressing the electric toothbrush on my tongueâa sensation that creeps me out. I even apply a moisturizing lotion that Jenna left months ago, the last time she slept over. Before Dad died.

I pull one of Dad's T-shirts over my head, my sleep outfit.

It seems important to view the night outside my bedroom window, to reassure myself that the moon still occupies its proper place, that the evergreen remains firmly rooted.

When I slide the puzzle from underneath the bed, I know where I am. That helps, because I have to fathom where I've been. I was there. I bobbed in that dinghy. My feet got wrinkly in sea water, sandwiched between a coil of thick rope and a fishing net. As I look at the puzzle, both of these objects are undetectable, mere smudges in the boat's interior. No, the details aren't clear, only the big picture. I accidentally pressed cheese onto a puzzle piece, and the cheese entered the puzzle with me. I tossed the cheese overboard, and somehow it came back out, into this world. Perhaps I thrashed it out when I was sinking.

I was there.

Those fingers of water I spied every time the

boat bobbed up resembled the edges of jigsaw pieces because they

were

the edges of jigsaw pieces. Only life-size.

While I rocked in that boat, the ancient Irish houseâthe only other section I've completedârevealed itself through the great white mass, whatever bizarre version of nothingness that was. I contemplate both images now, distant from each other on the puzzle board, placed approximately where they would go if the puzzle were completed: striped boat near the bottom right and, center stage, the house with its open window andâ¦No. I bend in closer. What's happened here? I angle my desk lamp so the light beams down directly and get close up again. Trust your eyes? In the puzzle, the window is now closed, shutters turned inward. No beckoning glow of light sneaks between the slats.

My dad was there, waving at the open window.

Only now the window's shut.

My dad was there.

I have to think and I have to think clearly, a

challenge when you've got the jitters. I make faces when I'm stressed. Poke my tongue into my cheek or jut out my lower teeth and chomp them repeatedly into my upper lip.

“Charmante”

âJenna always trots out her few French expressions when she sees my metamorphosis into Frankenstein's monster. Sometimes it helps, it does, to walk around stiff legged, contorting my features. Don't ask me why it helps, I'm clueless.

I dial her number, and she answers on the first ring. “James?” she moans sleepily.

James? I hang up.

Never before has it been anyone but me when her phone rings at this hour. But now it's James the Albert-Waldo phoning after midnight to discuss garlic, or make big smacking kiss noises, or coo a breathy, repulsive “I love you.” I don't think that fact should make me cry, but for some stupid reason I have to wipe my eyes.

My phone rings. Obviously she dialed star-six-nine. I turn it off.

Notes, Frannie. Make notes.

I open an old spiral notebook from algebra class and turn to an empty page.

Important Facts

. I write that at the top.

First time. Through the window

. But when I tried again, I couldn't do it. That means either: a) a fluke; b) I can't enter the puzzle the same way twice; or c) Jenna was with me and I'm the only one allowed in. I don't know why I think of travel in and out as something that has rules. Maybe it has no rules at all, maybe it's ruleless and I have no control at all. The puzzle will suck me in and toss me out at will.

No control at all?

I write that down too.

Second time. In the boat

. Even if I could go back in that boat again, I wouldn't want to.

Why did the cheese return with me?

Maybe nothing can stay that wasn't originally there, that doesn't belong?

The Great Woolly White.

That's what I'm calling void land, the world outside the puzzle. What is it?

“Frannie, are you still awake?”

I kill the light. “Going to sleep right now. Night, Mom.”

Fortunately she doesn't come padding down the hall.

Somewhere in my closet is a flashlight. I sidle around the room, steering clear of furniture and boxes. As soon as I shut myself inside the closet, I wave my hand around until it collides with the overhead string, then tug it to light the place. Unfortunately my closet is a big pigsty. I plow through old shoes, backpacks, stray mittens, Rollerblades that I could never learn to skate on, ditto a skateboard, comic books, piles of plastic rollers and other hair equipment like old brushes and a dead blow dryer, gross. I push aside a sleeping bag and finally find the flashlight.

A slow sweep of the beam across the puzzle board unveils each possibility, abandons it, suggests another: the dome of a church, a section of rocky cliff (the edge where rock meets sky), a couple of roofs assembled to suggest the houses they belong

to, part of a stone wall. Zigzagging the light over the floor, I locate the carved box. Discovered in darkness, as if unearthed from hidden recesses, the box assumes its true identity, a treasure chest. No gold or rubies but a fortune so much dearer: It brought me back my dad.

I remove the top to get the photo, protected now by a Baggie, sandwiched-sized.

Using my flashlight, I compare the photo image to the partial bits in progress on the board. What's the best route back in?

I'm not putting myself on any rocky cliffsâmy disastrous hike at camp was enough uphill and downhill for life. Roofs without housesâthat doesn't seem sensible. The church dome has a narrow balcony that wraps it, but as yet no church to support it. The church towers over the village, and the dome is the highest point. It was scary enough to be stranded in a dinghy surrounded by the Great Woolly White, but to end up perched on a narrow balcony, where with one false move, I might fall

into the GWW (my lovely legs scissored as if I had executed a really bad dive)âthat prospect is terrifying.

That leaves the stone wall.

According to the photo, there are several stone walls. The one along the shore is a safe location, perfect for a touchdown, but another stone wall along the side of the mountain is the worst of all places to find myself. These pieces I've put together so far could belong to either.

What am I going to do?

As I wonder in near darkness, my eyes drift to a mound of jigsaw pieces illuminated by a circle of lightâall of them mixtures and hues of coral and grayâone of many piles of sorted pieces around the edge of the puzzle board. What's weirdâno, mind-bogglingâis that the flashlight in my hand is not pointed in that direction. My arm's hanging by my side, and the flashlight, held loosely, points at an empty spot on the carpet. The carpet should be lit up. There should be a bright circle of fuzzy

green, but there's not. The direction of the flashlight and its circle of light have no relationship. They've parted company. I jerk the flashlight over, pointing at the coral-and-grays, to correct the mistake. I don't know why I do that. It's instinct to use my source to capture the lightâas if such a thing were possible, how absurd to try, and yet it works. When I move the flashlight again, the circle of light stays with it, once more in my control. I test the flashlight, looping curlicues, a treble clef across the wall, and arc the light back down. Where does it land? The coral-and-gray pieces.

What will these be when I put them together?

I have to study the photo again. Fortunately the flashlight beam cooperates, making me wonder if that light displacement really did happen. Near the church there's an orange houseâ¦No, some of these coral-and-grays have knobby ends tipped with dark green, and nothing around this orange house matches that. These pieces must compose this section in the hills beyond the town. What is it?

Some sort of long, low building? A garden abutsâthat could be the dark green. Those might be stone steps, a route down to the house where I spotted Dad. Steps, that's good, not too treacherous.

Before immersing myself in making matches, I prepare. I have no control, I remind myself, falling in and ejecting out. It could happen at any time. I dress in cargo pants, my own shirt, a sweater tied around my waist, clunky boots with serious treads. I'm not ending up in Ireland barefoot, bare-assed in Dad's big shirt.

It's one in the morning and I'm wired. The possibility of Dad is a caffeine jolt of epic proportions. I'm possessed. Determined. There is nothing braver, fiercer, and more glorious than the tiny ember of hope burning in my heart.