Freeglader (25 page)

‘That's the gardens fed. Now let's fill our milch-pails and take them back to the colony,’ one of them commented.

‘Honey for breakfast, deeeelicious!’ said another, her heavy eyelids fluttering.

Far underground, as the first load of moon-mangoes landed on the giant compost heap below, a gaunt youth glanced over from the raised ledge he was ambling along. The glowing light played on his short cropped hair. A second load tumbled down through the air, followed by a third and a fourth. The youth looked up and focused wistfully on the long tube they were emerging from, high up and inaccessible in the domed ceiling, far above his head. As he watched, half a dozen firemoths fluttered round the bottom of the

tube, and disappeared in, heading for the forest outside.

‘I wish

I

could leave,’ he murmured.

But that was not possible. There was only one way in and out of the Gardens of Light large enough for those who dwelt underground – and that was guarded at all times. He had no choice but to remain under the ground, roaming the paths and ledges, always bathed in the same unchanging pink light. Close to three weeks he had spent down there already, yet he'd only seen a fraction of the sprawling Gardens of Light, with their winding labyrinth of walkways and glowing tunnels, stalagmites and stalactites, fungus beds and drop-ponds.

Crossing a small bridge of opalescent rock, he heard the sound of steady chomping and looked down to see a brace of slime-moles in a steep-sided pit below him, chewing contentedly on fan-shaped fungi. A couple of glassy spindlebugs – heavy trugs swaying from their fore-arms – were passing along the walkways, dropping food down into the pits. One of them paused for a moment.

‘That's right. Tuck in, my beauty!’ it said, as one of the slime-moles below wobbled over and began devouring the fungus. ‘Will you look at that.’ The spindlebug

nudged his companion. ‘Her slime-ducts are bulging!’

‘Just as well,’ replied its neighbour. ‘The rate those young apprentices get through mole-glue! Filling their varnish pots every few minutes …’

‘I know, I know,’ said the first one, tutting. ‘It's not as though we're made of the stuff.’

‘No, but

they

are!’ said the second one – and the pair of them looked down at the slime-moles as they squirmed about, leaving trails of gleaming, sticky goo in their wake, and trilled with amusement.

The youth walked on. A herd of huge, lumbering milchgrubs being herded down to the great honey-pits for milking crossed his path. Shortly after that, a librarian apprentice – his eyelids puffy with lack of sleep – came hurrying towards him, an empty bucket clutched in his hand.

‘Run out of mole-glue, eh?’ the youth asked.

‘Uh-huh,’ came the gruff reply, and the librarian knight scurried past, his head down and eyes averted.

The youth sighed. Everyone knew who he was and why he was there – and no one, it seemed, wanted to be caught talking to him.

He climbed higher, up a bumpy ramp and onto a narrow ledge which hugged the arched wall. There were caves leading off it. Some were empty, some were being used for storage; from one, there came the soft murmur of voices.

Scratching his stubbly head, the youth paused for a moment and looked in. Half a dozen young librarian knights were sitting on low stools, each one bent over a

pot balanced on a small burner, stirring vigorously. There was a familiar smell, like singed feathers and burnt treacle. One of them noticed him, looked up, frowned and looked away.

The youth turned, and headed sadly off. No one wanted anything to do with him.

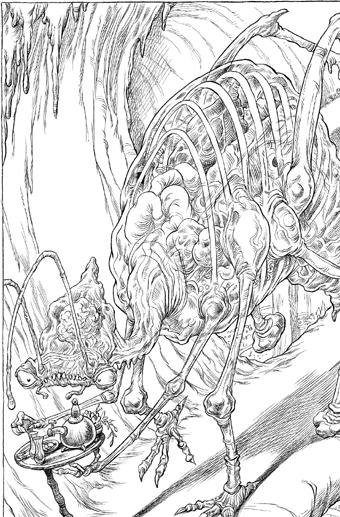

Then, just as he was rounding a jutting rock, he caught sight of an old spindlebug tap-tap-tapping its way along a broad ledge on an upper level. The creature was huge – far bigger than any of those who were tending to the fungus beds or slime-moles. In one of its front arms it carried a tray. In the other, a walking stick to help support its immense weight. Both the size and the yellow tinge to the outer casing indicated that the spindlebug was ancient.

As the two walkways converged, the creature came closer, the glasses and tea-urn on the tray clinking together softly. ‘Up so early,’ it said as it approached, its voice high and quavery.

The youth shrugged and pulled a face. ‘I can't sleep well down here,’ he said. ‘It's always so light. I never know whether it's day or night …’ He sighed miserably. ‘I miss the sky, the clouds, the wind on my face…’

The spindlebug stopped before him, and nodded. ‘You're here to prepare for your Reckoning,’ it said. ‘Use this time to reflect on your life, to contemplate your deeds and …’ It coughed lightly. ‘And your

mis

deeds. The time to leave will come all too soon.’

‘Not soon enough for me,’ the youth snorted. ‘Stuck down here in this prison…’

‘Prison, Xanth?’ the great, transparent creature interrupted. ‘You, of all people, speak of prisons!’

Xanth visibly shrank at the spindlebug's words, and when he spoke, his voice had lost its arrogant bravado. ‘You're right,’ he said quietly. ‘And I'm sorry. I know I can't compare this place to the Tower of Night…’ He shook his head miserably. ‘Oh, Tweezel, when I think of the years I spent serving the Guardians of Night; the evil I did, the misery I caused…’

Tweezel nodded. ‘Come now,’ he said gently. ‘Let us go and share a spot of tea together, you and I. Just like we used to do. Remember?’

Xanth's looked up into the spindlebug's face and saw his own reflected in the creature's huge eyes. Yes, he remembered the times he'd spent drinking tea and listening to the spindlebug's stories as a librarian knight apprentice. How he'd loved those quiet moments they'd shared, but his memories of them were poisoned by the knowledge that even as he'd smiled and sipped the fragrant brew, he'd been an imposter.

‘Are you sure?’ he said.

‘Certainly I'm sure,’ said Tweezel, his antennae trilling. ‘Follow me.’

Keeping close to the ancient spindlebug, and ignoring the muttered comments and angry glares from the apprentices they passed, Xanth followed him down the ledge and in through a narrow opening in the wall. Beyond the doorway, the space opened up to reveal a cosy, if rather cramped, chamber, furnished with a squat table and low benches. Tweezel ushered Xanth to sit

down and placed the tray down on the table in front of him, knocking his arms and elbows on the walls as he did so.

‘My, my,’ the ancient creature commented. ‘I swear this place gets smaller every day.’

Xanth smiled. Clearly it was Tweezel who had grown rather than the tea-chamber which had shrunk, and Xanth found himself wondering just how old the spindlebug actually was.

Quietly, methodically, the spindlebug placed one of the glasses under the spigot of the ornate wooden teaurn and turned the tap. Hot, steaming, amber liquid poured out, filling first one, then the other glass. Next, he added crystals of honey with a set of silver tongs, and a sprig of hyleberry blossom. As Xanth watched the familiar ritual, remorse and guilt welled up within him.

Tweezel noticed his tortured expression. ‘You are not the first to have felt guilt,’ he said. ‘And you certainly will not be the last.’

‘I know, I know,’ said Xanth, fighting back the tears. ‘It's just that…’

‘You wish you could undo the things you have done?’ said Tweezel as, with a slight incline of his head, he handed Xanth the glass of tea. ‘Change the decisions of the past? Put things right? Lift the heavy weight of guilt that is pressing down on your chest?’ He fell still. ‘Try your tea, Master Xanth,’ he said.

Xanth sipped at the tea, and as the warm, sweet, aromatic liquid slipped down his throat, he began to feel a little better. He set the glass aside.

‘Guilt is a terrible thing if you hide from it,’ the spindlebug said. ‘But if you face it, Xanth, accept it, then perhaps you can start to ease the pain you are in.’

‘But how, Tweezel?’ said Xanth despairingly. ‘How can I face up to the terrible things I've done?’

The spindlebug crouched down on his hind quarters, and sipped at his own tea. He didn't speak for a long time, and when at last he did, his voice was croaky with emotion. ‘Once, a long, long time ago,’ he said, ‘there was a couple – a lovely young couple – who were very close to me.

They

had to do a terrible thing…’

Xanth listened closely.

The spindlebug's eyes were half-closed, and he rocked backwards and forwards very slightly as he remembered a distant time.

‘It all began in old

Sanctaphrax, when I was a butler in the Palace of Shadows to the Most High Academe himself. Linius Pallitax was his name, and he had a daughter, Maris. Delightful young thing she was,’ he said, his eyes staring dreamily into the middle distance. ‘Heavy plaits, green eyes, turned-up nose, and the most serious of expressions you ever did see on the face of a young'un…’

He paused and sipped at his own tea. ‘Hmm, a touch more honey, I think,’ he murmured. ‘What do you think, Xanth?’

‘It's delicious,’ said Xanth, and drank a little more.

Tweezel frowned. ‘One day, a sky pirate ship arrived,’ he said. ‘The

Galerider

, it was called, captained by a fine, if somewhat unpredictable, sky pirate by the name of Wind Jackal. I remember coming to inform my master of his imminent arrival, only to discover that he – and his son – were already there.’

‘His son?’ said Xanth, who was beginning to wonder where exactly the story was going.

‘Aye, his son,’ said Tweezel. ‘Quint was his name. I remember the very first time I clapped eyes on him.’ He frowned again and fixed Xanth with a long, steady gaze. ‘In some ways, he was not unlike you,’ he said. ‘The same guilty tics plucking at his face; the same haunted look in his eyes…’

Xanth hung on his every word.

‘Of course,’ Tweezel went on, ‘it all came out later. He told me the whole story,’ he added, and smiled. ‘I've a good ear for listening.’

‘So what happened?’ said Xanth.

‘What happened?’ Tweezel repeated. ‘Oh, how cruel life can be. It transpired that, apart from his father who had been away at the time, the poor lad had lost all his family in a great and terrible fire. His mother, his five brothers, even his nanny – they had all perished in the flames. Somehow, being the youngest and smallest, he had managed to squeeze through a tight hole and had fled across the rooftops to safety.’ He paused. ‘He was full of guilt for being the only one to survive.’