Freeglader (34 page)

Ahead of them now, bathed in the fine, grey rain, were the slave-huts. Their own – a rundown, ramshackle hovel – was situated slap-bang in the middle of the row. The ground had been churned up, and they had to drag themselves on those last few strides through thick,

claggy mud that clung to their tattered boots. There at last, Heeb helped Rumpel up the three wooden steps, lifted the latch and pushed the door open.

A blast of stale, fetid air struck them in the face, a mixture of rotting straw, running sores and unwashed bodies. The two of them stumbled inside.

‘Shut that door!’ someone bellowed, before his voice gave way to a thick, chesty cough, which was soon joined by several others, until the whole hut was echoing with loud, febrile coughing.

‘Shut up! Shut up!’ a voice kept shouting from the far end. ‘Shut that infernal row!’

Heeb steered his brother down the central aisle of the hut towards the place where they slept – two wooden pallets covered with rank, mildewed straw. Forgetting for a moment the cuts and weals on his back, Rumpel fell down onto the makeshift bed – only to cry out and roll over the next moment.

‘Shut up!’ the voice came back with renewed vigour. ‘I'm trying to sleep here!’

‘Shut up yourself,’ someone else shouted back, and a

heavy clod of earth was lobbed at the complainer. ‘If you can't sleep, then you haven't been working hard enough!’

With everyone on different shifts, there were always some trying to sleep while others were coming and going; eating, drinking, muttering to themselves … dying.

Heeb knelt down beside his brother, pulled a small pot from his trouser pocket and unscrewed the lid. The sweet, juicy smell of hyleberry salve wafted up – though the pot was almost empty. Licking the grime from his finger as best he could, Heeb scraped out the dregs of the salve from the corners of the pot, top and bottom.

‘Lie still,’ he said, and proceeded to smear the pale green ointment around the worst of his brother's wounds. Rumpel flinched, and moaned softly when the pain got too much. ‘You've got to hold on a little bit longer,’ Heeb told him, as he massaged the salve into the skin. ‘We're almost done now. It's almost over…’

‘Al … almost o … o … over,’ Rumpel repeated, every syllable a terrible struggle.

‘That's right,’ said Heeb encouragingly. ‘The catapult cages have been completed.

And

the step-wheels and lance-launchers. And the boiler-chimneys. And the long-scythes will soon be ready as well.’ He tried to sound cheerful. ‘Won't be long now before we're finished…’

‘F … fi … finished …’ grunted Rumpel.

‘Glade-eater? Pah!’ said Heeb. ‘Goblin-crippler, more like!’ He shuddered as he replaced the lid on the small

pot. ‘You stay there, bro',’ he said gently. ‘I'll get us something to eat.’

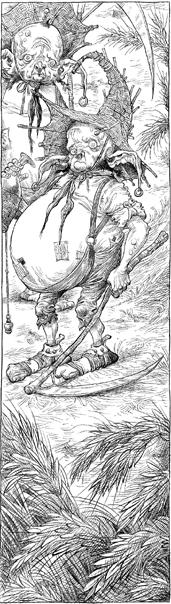

He climbed wearily to his feet, grabbed his and Rumpel's mug and bowl, and shuffled off towards the gruel-pot at the end of the slave-hut, which bubbled slowly under the watchful eye of a web-foot trustee. Heeb groaned. The fact that his brother was in a worse state than himself did nothing to lessen his own exhaustion. His cheeks were hollow, his eyes were sunken and his ribs stuck out like bits of kindling. Like his brother and the other low-belly goblins, he had little need for the belly-sling that hung loosely at his front – for just like them and all the others in the slave-hut, he was slowly being worked to death.

The gruel was grey and slimy and smelled of drains, and as it was ladled into his and his brother's bowls, Heeb couldn't help heaving. He filled the mugs with dirty water from the barrel and returned to the sleeping pallet.

‘Here we are,’ he said, placing everything down and pulling out a spoon from his back pocket. ‘Do you want me to feed you?’

Rumpel made no reply. Heeb wasn't even sure he'd heard him. Lying on his side, he was simply staring ahead, his breathing rasping and irregular.

Heeb swallowed anxiously. ‘Don't die on me,’ he whispered softly. ‘Not now. I couldn't bear it.’ Tears welled up in his eyes. ‘I told you, Rumpel, it's almost over. They've almost finished. Trust me, it's not long to go now. Not long…’

Lummel Grope dropped his scythe, stood up straight and stretched. ‘Earth and Sky, but this is backbreaking work, Lob,’ he said, and he reached inside his belly-sling to scratch the great, round, hairy stomach it supported.

‘You can say that again,’ said Lob. He pulled his straw bonnet from his head and mopped his brow on his sleeve. ‘And thirsty work, to boot,’ he added.

Lummel picked up the half-empty flagon by his side, pulled the stopper out with his teeth, and took a long swig of woodapple cider. ‘Here,’ he said, handing it over to his brother.

Lob wiped the top with the palm of his hand and did the same. ‘

Aaah!

' he sighed. ‘That sure hits the spot.’

The two brothers were in the middle of a blue-barley

field. Half of the crop had already been scythed down and gathered up into neat, pointed stooks. The other half was still waiting to be cut and bundled. It was over-ripe, with the heavy ears of barley showing the first signs of spoil-bloom, and no matter how hard the two low-bellied brothers worked, both of them knew it could never be fast enough.

‘If only it weren't just the two of us,’ Lummel grumbled.

‘I know,’ said Lob, nodding sadly. ‘When I think back to last year …’ He shook his head miserably. ‘I just hope and pray the others are all right.’

Lummel took the flagon back, and tipped another mouthful of cider down his throat.

‘Rumpel, Rudder, Heeb, Reel …’ Lob's eyes welled with tears at the thought of their absent brothers. ‘Dragged off to those accursed Foundry Glades like that…’ He swung his arm round in a broad circle that included the farm-holdings owned by their neighbours, their fields as full of uncut blue-barley as their own. ‘The Topes, the Lopes, the Hempels … Half of them already gone, and the other half waiting to be rounded up and carted off with the rest…’

‘And we'll be next, you mark my word,’ said Lummel. ‘Any time now those flat-heads'll be back. And this time, it'll be to send us off to war.’

‘And it won't just be us low-bellies, neither,’ said Lob. ‘No one's going to be spared this time round. Gonna send us all off to fight, so they are. And then what's to become of the harvest? You tell me that.’

Lummel nodded sagely, and the two brothers stood in

the field, side by side, passing the flagon back and forth as they surveyed the sprawling patchwork landscape of fields, villages and settlements spread out before them.

The Goblin Nations had come such a long way since its beginnings as a single gyle goblin colony, with tribe after tribe from all the major clans settling down as neighbours. Peaceable symbites had arrived first; as well as the gyle goblins, there were tree goblins, web-foots and gnokgoblins, settling round the dew ponds and in the Ironwood Stands. But later, others had joined them – warrior-like goblins who, despite their traditional root-lessness, had become increasingly attracted to this more stable and reliable way of life.

Tusked and tufted goblins, black-ears and long-hairs, pink-eyed and greys – they had constructed nondescript huts at first, often clustered round a totem-pole carved from the last tree left standing when a patch of forest was cleared. Later, some individual tribes had branched out – both geographically and architecturally – building towers and forts, round-houses and long-houses. Even some groups of flat-heads had seen the advantages of settling down and had taken land for themselves where they'd erected their own distinctive wicker hive-huts.

The two brothers stared ahead in silence at the scene. In the middle distance, the jagged Ironwood Stands where tree-goblins dwelt and long-hairs trained were silhouetted against the evening sky. Due south and east, the flat-heads' and hammerheads' wicker hive towers broke the distant horizon where, even now, dark forbidding clouds were gathering.

Further to the north, beside the mist-covered webfoots' dew ponds, the pinnacles of the gyle goblin colonies glinted in the rays of the sinking sun, while far to their right, in the partially cleared forest areas, they could see smoke spiralling up out of the chimneys of the huts in the new villages – some not yet even blooded – where the latest tribes and family groups to arrive had begun to settle.

Lob's face tightened with anger. ‘Why can't the clan chiefs just leave us in peace? Why must we go to war? Why, Lummel, why?’

Lummel sighed. ‘We're just simple low-bellies,’ he said, slowly shaking his head. ‘The mighty clan chiefs don't concern themselves with the likes of us, Lob.’

‘It's not right,’ said Lob hotly once more. He nodded round at the blue fields, the barley swaying in the rising easterlies. ‘Who's gonna harvest that lot, eh? No one, that's who. It'll just get left to spoil in the fields.’

‘S'already starting to turn,’ said Lummel.

‘‘Xactly,’ said Lob. ‘And what's there gonna be to eat on those long, cold, winter nights then? You tell me that!’ He took the flagon back from his brother, drained it and wiped his mouth on the back of his hand. ‘One thing's for certain, those high and mighty clan chiefs won't go hungry.’

‘You're right, brother,’ said Lummel. ‘They'll be feasting in their clan-huts while we do the fighting and dying in this war of theirs.’

‘Clan chiefs!’ said Lob, his voice heavy with contempt. He spat on the ground. ‘We'd be better off without them.’ He picked up his scythe, turned his attention to the waiting barley and began cutting with renewed vigour. ‘What

you and I need, brother, are the friends of the harvest…’

‘Lob,’ said Lummel, his voice suddenly hushed and urgent.

‘You heard what was said at that meeting,’ Lob continued, scything furiously. ‘There's a whole load of goblins like us, from every tribe and all walks of life who think just the way we do…’

‘Lob!’

Lob paused and looked up. ‘What?’ he said. ‘It's true, isn't it?’

And then he caught sight of what his brother had already seen – a long line of scrawny web-footed goblins tramping through the fields towards them from the northeast under heavy armed guard. They were dripping wet from head to toe. Clearly, the flat-head guards had interrupted their sacred clam-feeding and dragged them out of the water without even allowing them to return home for a change of clothes. The thin, scaly creatures looked lost and forlorn away from the dew ponds and the giant

molluscs they tended that lived in their depths.

Lob gasped. ‘By Earth and Sky,’ he whispered, his voice trembling, ‘if they're picking on harmless symbites now, then no one in the Goblin Nations is safe any more.’

‘Oi, you two!’ one of the flat-head guards bellowed across the blue-barley field. ‘Get over here and join the ranks at once.’

Lob and Lummel looked at one another, their hearts sinking. The moment they had both been dreading had arrived, and much earlier than their worst fears. Where were the friends of the harvest now?

‘Look lively!’ shouted the flat-head. ‘You're in the army now.’

‘But … but the harvest,’ Lob called back. ‘We haven't finished bringing it in…’

‘Forget the harvest!’ the flat-head roared, his face blotchy crimson and contorted with rage. ‘Let it rot! A richer harvest by far awaits us in the Free Glades, and all

you

have to do to reap it is to follow in the tracks of a glade-eater!’