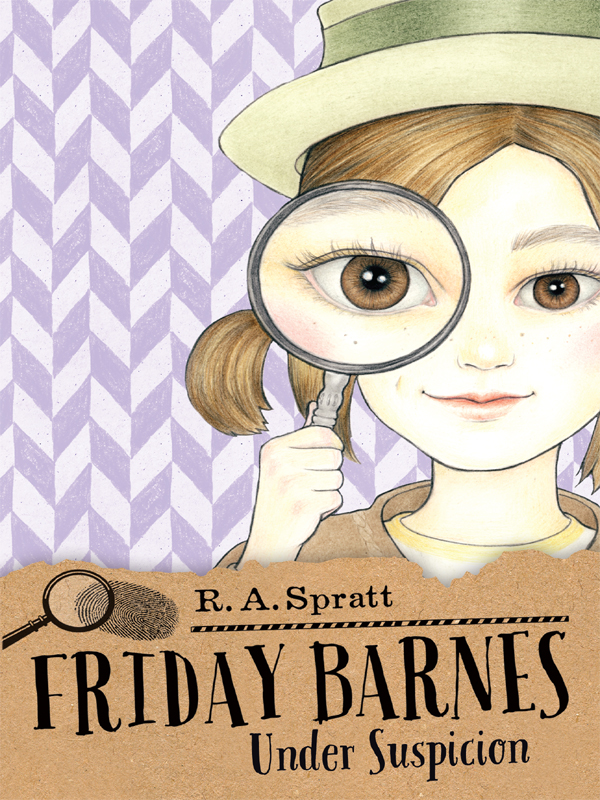

Friday Barnes 2

Authors: R. A. Spratt

Who knew boarding school could be this perilous!

When Friday Barnes cracked the case of Highcrest Academy's mysterious swamp-yeti, the last thing she expected was to be placed under arrest.

Now, with the law on her back and Ian Wainscott in her face, Friday is not so sure boarding school was the smartest choice. From a missing or not-so-missing calculator to the appearance of strange holes in the school field, she is up to her pork-pie hat in crimes â and she swears not all of them are hers.

There's also new boy Christopher, who has taken quite a shine to Friday, to contend with.

Can Friday navigate the dangerous school grounds and decipher a decades-old mystery without getting caught in an unexpected love triangle?

To Mum and Dad

Friday Barnes and her best friend, Melanie Pelly, were sitting in the dining hall at Highcrest Academy, enjoying second helpings of chocolate cake. They'd had a long day solving crime and saving the school's reputation so Mrs Marigold, the cook, felt they had earned an extra serving of dessert. But their calorie-induced bliss was about to be interrupted.

âBarnes,' snapped a voice from behind them.

Friday and Melanie turned around.

The Headmaster was standing next to a uniformed police sergeant.

âWhat's this?' asked Friday. âAm I getting some sort of citizenship award for everything I've done for the school?'

âNo,' said the Headmaster soberly, âI'm afraid not.'

âFriday Barnes,' said the police sergeant, âI have to ask you to come with me.'

âWhy?' asked Friday.

âBecause I'm arresting you,' said the police sergeant. âYou are not obliged to say anything unless you wish to do so, but whatever you say or do may be used in evidence. Do you understand?'

âNot really,' said Friday. âNot the situation anyway. But I do have a large vocabulary and as such have no trouble understanding the meaning of your words.'

The police sergeant had dealt with much more intimidating people than Friday resisting arrest, so he simply took the matter in hand. He pulled Friday's chair back for her while she was still sitting on it, took her by the elbow and guided her to her feet.

Friday was mortified. She didn't have to look up to know that everyone in the room was staring at her. This would be yet another reason for all her

rich classmates to snigger and laugh at her. There was nothing she could do. She was the most exciting spectacle in the dining room since Mrs Marigold lost her temper with a vegetarian student-teacher and dumped a blancmange on his head.

âIf you'll come with me,' said the police sergeant, although Friday could barely hear him through the rushing sound in her ears. People always marvel that holding a seashell to your ear replicates the sound of the sea, but in the seconds before you faint, the movement of blood rushing out of your brain replicates the sound of the sea too.

Friday saw Melanie's concerned expression, then movement made her look across. Ian Wainscott, the most handsome boy in school (also the most infuriatingly smug boy in school) was entering through the back door. Friday watched his face as he took in the scene. He seemed surprised for a moment, then he caught Friday's eye and his face returned to its normal apathetic mask.

The police sergeant started pulling at Friday's arm and the world seemed to return to normal speed. Her ears started to process sound again, just in time to hear the first murmurs of malicious gossip.

It was times like this when Friday wished she didn't have a brain like a super computer. Having a photographic memory meant that the words, and the associated hurt, would be accessible in the long-term storage of her brain's neural matrix forever.

âTypical scholarship kid, probably been stealing,' whispered Mirabella.

âMaybe she's being arrested for wearing those brown cardigans,' said Trea. âShe should get five to ten years for crimes against fashion.'

âPlus another ten for the green hat,' said Judith.

Now dozens of people sniggered. That was the last Friday heard of her peers as the dining room door flapped closed behind her.

A squad car with lights flashing was parked at the top of the school's driveway.

âThe Headmaster is going to hate that,' said Friday. âIt's a bad look for the school.'

âThe Headmaster will be grateful I'm taking you off his hands after what yâwagh!' said the police sergeant as he was interrupted mid-lecture because he had fallen into a hole about one foot round and one foot deep.

âOw, that hurt,' said the police sergeant, rubbing his knees.

âI wonder who put that there?' said Friday. She inspected the hole. It looked like it had been dug out by hand.

âThis crazy school,' muttered the police sergeant. âThere's always something going on. Rich kids with their weird pranks or bitter teachers with their revenge plots. The sooner we get out of here, the better.'

Friday looked back at the main building. She had a lump in her throat and her eyes started to itch. She knew she wasn't suffering from hayfever because it wouldn't be spring for another six months.

Friday wasn't terribly in touch with her emotions, but she was able to deduce that she was upset. Being forced from Highcrest Academy had affected her more than she would have imagined. The police sergeant was entirely right. Highcrest Academy was full of obnoxious children and strange teachers, but it had also become her home. She had friends ⦠well, one friend. And she received three warm meals a day. So despite the gothic architecture and the even more gothic attitudes of the staff, this place had made her feel safe and needed â in a way her family home

never had. As the squad car started to pull down the driveway, Friday hoped this would not be the last time she saw her school.

The police car wound its way through the rolling countryside to the nearest town. A female police constable was driving. They were heading for Twittingsworth, a fashionable and well-to-do rural area whose tax base owed more to the weekend homes of city bankers than the local farmers.

âSo what crime am I being accused of committing?' asked Friday.

âWe'll discuss all that in the formal interview,' said the police sergeant.

âWhy, is it some sort of surprise?' asked Friday.

âIt's a very serious offence,' said the police sergeant. âWe don't want to jeopardise the case by deviating from correct procedure. We're going to do this by the book. There will be a lot of scrutiny. The national counterterrorism squad has been alerted.'

âCounterterrorism!' exclaimed Friday. âBut IÂ haven't done anything.'

The police sergeant snorted. âSave it for the interview.'

The police station was an old stone building, built back in the day when pride had been taken in the appearance of official institutions.

Friday had not been handcuffed. No doubt there were rules about handcuffing children. She also thought it unlikely that her own thin, spindly wrists could be contained by the same handcuffs that would be needed to restrain a fully grown man.

It was the lady police constable who led Friday into the building, taking her through to an open-plan office area where there were half-a-dozen desks and mountains of paperwork cluttered everywhere. There was one separate office partitioned off at the end of the room. No doubt for the sergeant.

Everything inside the police station had been painted grey-green except for the cheerful posters on the wall, featuring famous athletes urging citizens to be respectful of women's rights.

Friday was underwhelmed. She had imagined the inside of a police station to be a more exciting place, but she supposed they could not put up gruesome crime scene photos on the wall. As a result the police station looked like an average boring office.

Friday sat down on a wooden bench outside the interview rooms. The bench reminded Friday of the one outside the Headmaster's office, although on the whole it was more comfortable. Plus the police station had less of an air of impending doom than the Headmaster's office.

On the far end of the bench sat a man who looked like a vagrant. But a strangely large and athletic vagrant. It was hard to gauge his height because he was sitting down, but he must have been well over six feet tall. He had thinning blond hair and a rough beard. His clothes were old, worn and crumpled. And Friday noticed that he smelled quite distinctly of mould, even though she was trying her very best not to breathe through her nose. He was handcuffed to the bench. Friday felt like she had been put next to the lion enclosure at the zoo.

The lady police constable bent down to speak to Friday, in what she clearly hoped was a comforting

fashion. âWe've left a message for your mum and dad,' she said, âso they should be here soon.'

âI doubt it,' said Friday. âThey never check their messages. They only have an answering system because they find it less irritating than letting their phone ring.'

âHow do you get in touch with them then?' asked the lady police constable.

âI don't,' said Friday. âI suppose I could send an email to one of my mother's PhD students and ask them to speak to her in person. That's what I did the time I broke my ankle on a geology excursion.'

âYou did?' asked the lady constable.

âYes,' said Friday, I needed to let her know I wouldn't be home because the rescue helicopter couldn't pick me up from the cliff face until daylight. But I haven't done that for ages, because we're not allowed to have email access at Highcrest Academy. They have a strict anti-technology policy. They're frightened students will use handheld electronic devices against the staff.'

âReally?' said the lady police constable.

âYes,' said Friday. âBut students find ways around it. I know a girl who only took art so she could sketch incriminating drawings of her history teacher and post them to her lawyer.'

âThis is a problem,' said the lady police con stable. âWe can't interview you until a family member is present.'

âBy “interview” you mean browbeat me into confessing, don't you?' asked Friday.

âWell, um â¦' began the lady police constable.

âIt's all right,' Friday assured her. âAs a fledgling detective I'd enjoy seeing professionals at work. Will you do “good cop, bad cop”, or are you doing it already and that's why you're being nice to me?'

âWell, er â¦' said the lady police constable, blushing a little at having been caught out by an eleven-year-old.

âThis is exciting,' interrupted Friday. âCall my Uncle Bernie. He's an insurance investigator. I'll write his number down for you. He'll come right away. IÂ can't wait to get started.'