From the Forest (16 page)

Authors: Sara Maitland

So if, just occasionally, Hansel grows restless and slips off to see Gretel in her pretty little house in the forest, his wife has no problem with that. It is so much better than the equally occasional screaming, sweating nightmares. Sometimes she will invent a message, or give him some small object to take with him; always she will send her love, and always before leaving Hansel will kiss her affectionately.

And so it is today. His eldest daughter brings the baby round after Mass and they all eat together in merriment; but after the meal he feels that tug at his heart and he cannot settle. He dandles the baby, bouncing her on his knee, while she crows and grins widely. ‘Gretel, Gretel,’ he coos to her, hoping it will dull the tug and let him stay. But eventually he gets up, gives the baby back to his daughter, smiles at his family, says that he thinks he will go over to Gretel’s. He does not notice his wife shake her head minutely at his daughter, who is about to suggest coming with him. He kisses both women and goes out.

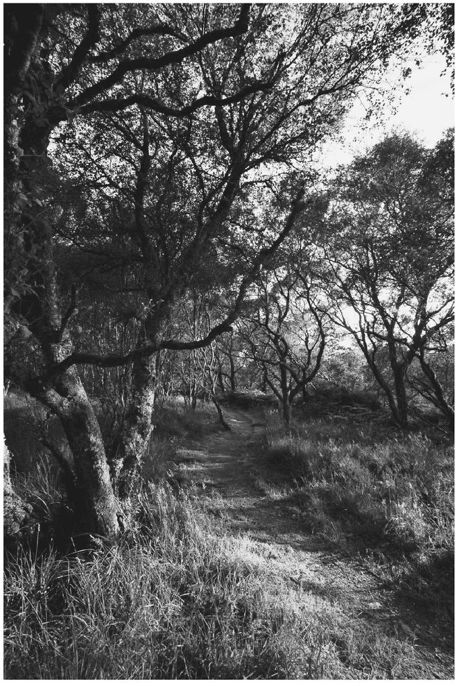

In recent years he has marked the path to Gretel’s house with white stones. It is a little joke, and he does not know if she has noticed. He watches for them one by one, and at the same time he looks at the trees which are just reaching the fullness of leaf canopy, darkening from early bright gold green to full rich green, so that less sun is finding its way through to the ground litter. Where the wood opens out into pasture ground there are wild roses, and somewhere deep in the hidden places he can hear a nuthatch chattering – zit, zit, zit – surprisingly loud for such a small bird.

Even as he walks his tension eases and he feels calmer. He suspects that Gretel no longer has this nagging need of him that he has of her – that she has somehow found her whole self inside herself and does not need him to show her who she is again. But he does not feel that this matters. He is happy as he walks through the forest in the afternoon sunshine.

The path curls round just before it breaks out of the trees and into her clearing, and for a moment he sees her – she is surrounded, covered in a cloud of white butterflies that are dancing around her face, over her shoulders and above her head. She is standing quite still, basking in their attention. He finds her briefly perfectly beautiful, and then he makes some accidental-sounding noise so that when he comes out into the clearing she has dismissed the fluttering flock and is standing there smiling at him. The chooks in their pen set up a cackle of pleasure and she calls, once, not very loudly, ‘Hansel,’ and he knows she is glad he has come.

He stands by her gate for a moment, and almost without thought reaches out for a sugar plum and pushes it into his mouth with an oddly greedy gesture for a grown man. She laughs and says:

Nibble Mouse, nibble mouse,

Who is nibbling at my little house?

It was what the witch had said the very first time, but now he laughs, the last of his restless tension draining away in the complete ease of her presence. He is fifty years old and munching sugar plums like a child again.

‘Me,’ he says, and they hug warmly.

In the kitchen she makes him drop scones, the batter waiting in a bowl beside the stove as though she had known he was coming. They eat them with the honey her bees have made. He notices she is putting on weight a little now, at last; it does not dim her loveliness for him. He watches her with pleasure as she moves graceful about her little house. They talk about little Gretel, about the hornbeam pollarding at the west end of the wood and about her strawberries and the white currants that are setting their translucent moon fruit along her wall.

Later they go for a walk. She puts her arm round his waist and her head leans lightly on his shoulder. There is a little party of long-tailed tits, ridiculous and agitated, bustling along ahead of them; tiny pinkish balls of feathers with absurdly long tails. They do not talk much now. It is all hushed green gold and the wind has dropped away.

There is a tiny rustle, almost too small to hear, and across the path there is a ripple, a wave, a rope shaken by invisible children. It is a weasel and her two kits, in a line, crossing the path ahead of them; elegant, wicked killers with big dark eyes. The mother weasel pauses, stares at them, her white underbelly vivid on the forest floor; and then they are gone.

When Hansel looks at Gretel he sees that she is crying; silent tears run down her cheeks and she does not move to wipe them away.

‘Gretel,’ he says very quietly so as not to break her stillness.

‘I killed her,’ she says, in the same whispered tone. ‘I killed our witch. I pushed her into the oven and I killed her dead. She was like a weasel, wild and fierce and free, and I killed her.’

‘You had to,’ he says, ‘you had to. She would have killed and eaten me.’

‘Would she, Hansel? Would she? I try to remember and it is all like a story. Are they true, the stories? Are they ever true?’

‘Sometimes they are true,’ he says with great gentleness. She turns and lays her head against his chest; they stand in the sunlit wood and he holds her. ‘Here is a true story. Once upon a time there was a brave little girl; she had a foolish brother, a weak and pathetic father, and an evil, cruel stepmother who certainly wanted to kill her. But in terrible fear, in the raging of danger and sadness and terror, she kept her head. She rescued them both. That is a true story.’

‘And the gingerbread house? Really? And a forest that big? We know it is not that big.’

‘I don’t know,’ he says, ‘I’ve never known. But we were away for months and we survived. Perhaps we dreamed the witch, I don’t know; perhaps we made her up so that we had some sort of story to tell. It was a dark place, a dark time and we were somewhere so bad we had to tell a story to make it bearable, to allow us to come back into the sunshine. That is what the stories are for.’

‘Oh,’ she says, ‘thank you.’ She pulls away and walks on a little and he follows her, watching her spine move as the weasels’ had, flexible, graceful, lovely.

When she turns back to him she has stopped weeping, but she still looks sombre.

‘You see, sometimes now I think I may be turning into our witch. I live in my little house and put out sweeties for the children. I hope they will come along the path, but when they do I sometimes feel cross or ragged with the disturbance. I wouldn’t like it if they killed me and then went home and boasted about it.’

‘Don’t worry,’ he says. ‘I will not let them kill you. It is my turn to protect you now. I have grown less foolish.’

She puts her arm back round his waist and they follow the little path round towards her house.

He is shaken, because he has told the story and believed the story for years. He is shaken by her pure honesty and by her quiet, lovely life. He tries to sound adult and thoughtful,

‘Anyway, whatever really happened, we did learn a lot, didn’t we?’

Suddenly she laughs and says, ‘Well, we learned never to use breadcrumbs to make way markers with, because the birds will eat them.’

‘Gretel,’ he remonstrates. And then, ‘OK. That was not my best moment.’

She looks slyly at him, her shadowed moment melting away now, just as his do when they are together. ‘I’ve noticed your white stones,’ she says. ‘I like that.’

When they reach the gate he leaves her. He can feel that she needs to be alone now, to be silent and settled. She goes through the gate and then turns and watches as he walks across the clearing. Just when he reaches the edge of the trees she calls, ‘Hansel!’

He turns and looks back at her.

‘Come again soon.’ She has to raise her voice so he can hear her.

‘Yes,’ he says, ‘of course.’ Then he waves and sets out for home.

5

July

Great North Wood

O

ne hot July morning I set out to find a hidden forest. It was perhaps the oddest of my woodland walks, and, strangely, seemed to bring me closest to at least one aspect of what I was searching for – the roots of the fairy stories. I went with Will Anderson, the ecologist, to see what we could find of the Great North Wood.

Once upon a time the whole country may not have been all forest, but there was certainly forest where now there is not. This is most noticeable around big cities which expanded fast in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, moving out beyond their traditional walled boundaries and spreading into areas which had been wooded or farmland, and which had, historically, supplied food and fuel to the cities before there was easy transport, by canal, rail and then road, and eventually by ship and aeroplane, which could bring these necessities quickly and more cheaply from further away. There is a complex relationship here between the rising population of a city, the comparative values of land for production and land for housing, and the development of transport infrastructures, but wherever you choose to begin the circular calculation, you end up with less forest and less productive agriculture and more roads, railways and domestic housing surrounding the historic urban core.

During the Industrial Revolution, London grew faster than anywhere else in Europe. In 1674 it had a population of half a million, which doubled over the following century and a quarter. All major cities in Europe expanded in the nineteenth century, but in London the growth rate exploded: in 1801, when the first national census was taken, it was just over 1 million; but by 1900 it had risen to 6.7 million. It is difficult to realise just how rural many areas, which are now densely populated, were until comparatively recently. East of the City, where London now extends for miles into Essex, there was until well into the nineteenth century little more than a few villages and a great swathe of market gardens, small dairy farms and country lanes. One way of measuring this change is to see how many new parish churches were built in any given area during a specific period – the old churches, more than adequate to serve their local populations, had to be supplemented in a massive church-building boom to accommodate (and control) rapidly expanding populations. In 1851 Henry Mayhew, a writer and journalist, published his carefully researched

London Labour and the London Poor

, a very moving description of the plight this vast new population. The response to his book makes it clear that the educated and literary classes, living just a few miles away in the City and West London, had simply not realised how fast the East End of their own city was growing and under what pressures of poverty its population was living. The pressure was cultural as well as economic: these new residents were first- and second-generation immigrants, not only from overseas, but from rural communities all over southern England and beyond. Victoria Park in Hackney, like other similar green spaces, was an early response to what was seen as deprivation, and the establishment of the green belt (still under pressure today) was a later attempt to address the same problem.

The cumulative effects of the Agricultural Revolution of the eighteenth century and the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth led to a massive shift from rural to urban life, and with it, to an extensive loss of countryside around towns and cities. One large and conspicuous loss of ancient woodland in southern Britain in the modern period has been the disappearance of the Great North Wood.

Once upon a time there was a swathe of ancient oak forest on the raised ground south of the Thames, about four miles south of the city of London, covering the area which is now Dulwich, Sydenham, Penge, Norwood and parts of Croydon, and running as far north as Camberwell. The Anglo-Saxons seem to have named it ‘the North Wood’ to distinguish it from the even larger woods to the south across the Weald. During the reign of Henry VIII there were dense woods either side of the main road from Brixton to Streatham, and therefore also the usual steady stream of complaints that felons and other miscreants escaped from London and hid out in the forest, preying on travellers and endangering law and order. This forest was similar to forests all over the country: a mixture of thick wood, heath and farm land, with stock, especially pigs, grazing within the woods. Being so near to the large and growing capital, the forest was always going to be vulnerable to pressures for building materials, fuel and land itself, and in addition, the Crown extracted a great deal of timber for use in the royal dockyards at Deptford, nearby on the Thames. When Oliver Cromwell seized the forest from the Archbishop of Canterbury – its hereditary owner since the Conquest, when William I gave it to Lanfranc, his first Archbishop – there was still 830 acres of forest, but fewer than 10,000 oak pollards. Inevitably, by the mid-seventeenth century, it was a forest in decline. Nonetheless, the absence of any old churches or other medieval or Tudor structures within the area strongly indicates that it stayed wild and under-inhabited until surprisingly late.

In

The Journal of the Plague Year

(published in 1772, but carefully researched), Daniel Defoe, who lived not far away in Tooting, commented:

And as I have been told that several that wandred into the country on Surry side were found starv’d to death in the woods, that country being more open [unpopulated] and more woody than any other part so near London, especially about Norwood and the parishes of Camberwell, Dullege and Lusume [Lewisham].

1