From the Forest (26 page)

Authors: Sara Maitland

I described ‘The Magic Table, the Golden Donkey and the Club in the Sack’ in the previous chapter, but it is only one of many similar stories. In ‘The Two Brothers’ the small boys, by accident, acquire a magical ability to produce two gold coins every morning; terrified by this, their father abandons them in the forest, but – despite the fact that they are not poor – they apprentice themselves to a huntsman, who, being a forest worker, is of course kind, thoughtful and honest. Eventually, through their hunting skills and forest lore rather than their gold, one of them marries a princess and becomes King.

11

In ‘The Thief and His Master’, a father apprentices his son to a robber – with surprisingly favourable results. In ‘The Poor Miller’s Apprentice and the Cat’, the ‘simpleton’ hero wins a mill, a beautiful horse and a rich bride through faithful seven-year service to a cat. Even in the deliberately funny tale ‘The Boy Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was’, the initial impetus to the youth’s prosperous adventures was his father’s determination that he should learn a decent trade because he was so stupid.

The importance of work applied to girls as much as to boys. In ‘Mother Holle’, for example, as I related earlier, the heroine is forced down a well-shaft by her cruel stepmother. She arrives in another world, and eventually returns, coated in gold dust. But the reason for her success was that she took service with an old woman, and ‘attended to everything to the satisfaction of her mistress and always shook her bed so vigorously that the feathers flew about like snow-flakes. So she had a pleasant life; never an angry word and to eat she had boiled or roast meat every day.’ So when she goes home, she has earned her reward. Her stepsister, on the other hand, is idle; she accepts the old woman’s offer, but ‘on the second day she began to be lazy and on the third still more so, and then she wouldn’t get up in the morning at all. Neither did she make Mother Holle’s bed as she ought.’ So the shower of pitch, ‘which clung fast to her and could not be got off as long as she lived’, was a fitting payment for her failure.

A significant number of the women in the fairy stories are self-employed, independent and skilled. They often have a relationship – positive or negative – with spinning. Although most women could and did spin domestically, if she became good at it, it was one of the few ways a woman could become financially self-sufficient. (Midwifery was an alternative career.) At her trial in 1431, Joan of Arc was immediately inflamed by the suggestion that she worked as a shepherdess: on the contrary, she snapped, she was a highly skilled spinster.

12

To be honest, there are a few stories in which the heroine – and it is always a heroine – succeeds by getting out of work and into leisure. However, these stories are always triggered by the unreasonable demands of more powerful individuals, and they are nearly always humorous. ‘The Three Spinners’ is a nice example: an ‘idle’ girl is trapped by her mother’s stupidity and the greed of the Queen into having to spin a vast quantity – ‘three whole rooms full’ – of flax, even though ‘she could not have spun the flax, not if she had lived till she was three hundred years old and had sat at it every day from morning to night’. She is in despair when three strange old ladies come to her aid. They are particularly ugly: ‘the first of them had a broad flat foot, the second had such a great underlip it hung down over her chin and the third had a broad thumb’. The deal is – and there is always a deal – that they will spin the flax for her and in exchange she must invite them to her wedding, introduce them as her aunts and invite them to sit on the top table. All goes well. The Queen is so delighted with the young woman’s diligent labour she announces: ‘You shall have my eldest son for a husband even though you are poor. I care not for that; your untiring industry is dowry enough.’ The wedding is arranged; the girl keeps her promise and the old women arrive, ‘strangely apparelled’; her fiancé is startled that his bride should have such ‘odious friends’, and questions them about how they came by their peculiar features. They reply, by turns, ‘By treading,’ ‘By licking’ and ‘By twisting the thread’ (the three core actions of spinning with a wheel). On hearing this, ‘the King’s son was alarmed and said, “Neither now nor ever shall my beautiful bride touch a spinning wheel.” And thus she got rid of the hateful flax-spinning.’ This is one of the sillier, shorter and more pointless of the

Märchen

, and it reads to me like a women’s joke story, rather than a profound moral lesson.

Work is always good. When the dwarves first saw Snow White asleep in the cottage, they responded with a generous delight. ‘“Oh heavens! Oh Heavens,” cried they, “what a lovely child!” and they were so glad that they did not wake her up but let her sleep on.’ However, the next morning, they make their position very clear: ‘If you will take care of our house, cook, make the beds, wash, sew and knit, and if you will keep everything neat and clean, you can stay with us and you will want for nothing.’ Skilled work learned and performed diligently is a source of dignity and well-being in fairy stories; the dwarves epitomise that dogged commitment, particularly as they are self-employed rather than waged.

In

Uses of Enchantment

Bettelheim suggests that, in these stories, becoming a king or queen is not about political power or even power over others, it is about independence, freedom to manage one’s own life and not be under the control of someone else. Because he sees all fairy stories as being directed at children by adults, he therefore sees this standard resolution to the stories as a metaphor for becoming a grown-up. I agree with his initial observation – the kings in the stories never seem to perform any monarchical or demanding duties – but I think he has missed the point: the idea is that profitable self-employment is the most desirable state, and that skilled hard work is what will gain it for you.

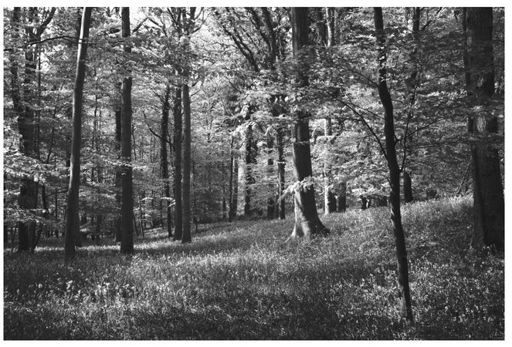

After I parted company with John Daniels, I left the car and walked through the woods, which grow close around the mine. I knew I was walking over the dark tunnels in the autumn sunshine. Here the trees were close together and had a dense green canopy, through which I could see very little of the sky. The undergrowth was thick too; within less than a hundred yards I could longer see the road or the mine head. It was nearly as quiet as it had been underground. I became convinced that there was a symbiotic relationship between this sort of mining and the forest that enfolds it. Free Mining rights died out on the open peaks of Derbyshire and elsewhere. Perhaps the mines need the forest, and without the trees to hide the mines and to protect the privacy and independence of the Free Miners, such traditions cannot survive. Deep in the forest you can escape the gaze and control of the ‘management’ and the necessary contemporary rules and regulations; going underground, you can be free to make your own life through courage and cunning. Even when the forest above you is reordered, replanted and tidied up in ways which turn out to be contrary to, and not as successful as, the old free forest where the trees grew huge and magnificent, you still maintain your right to carve out your own life by skill and hard work. Free Miners mirror the heroes of fairy stories. And both are imperilled by modernity.

The Seven Dwarves

Once upon a time there were seven dwarves.

One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven.

Once upon a time there were seven dwarves. They lived together in a small house a long way from anywhere, high in the mountains. Montane forests are dwarf forests; the trees here grow short and gnarled – scrubby juniper, wind-warped birches and skinny quivering aspen. As the track climbed upwards out of the sweet woodlands below, the rocks broke through the surface, grey and rough faced, the trees became more widely spaced and the grass and moss and lichen between them was tussocked and boggy. The winters were long and dark here, and the hare put on white coats to camouflage themselves from eagles in the snow. It was harsh craggy forest, with its own fierce beauty and here the dwarves had built their little cottage, as snug as they could make it and with long views over the world from the front door.

But as much as the forest where they lived was dark and demanding, the forest where they worked was far more so. For these dwarves, as dwarves tend to be, were miners, and each day they put on their iron-toed boots, hefted their picks and shovels, opened one of the round trap doors they had made in the mountainside, and went down and down into the underground forest where their treasure was buried.

Because, once upon a time, there were other forests. They were very different forests from the ones we know now. There were trees, but not the trees we know – there were

Equisetales

,

Sphenophyllales

,

Lycopodiales

,

Lepidodendrales

,

Filicales

,

Medullosales

and

Cordaitales

. There were plants, but not the plants we know – no flowers, no seeds, no lignin, no osmosis, strange fleshy growths. And, so long ago that the continents were still travelling and meeting and dancing with each other and tossing up mountain ranges in their dangerous embrace, these older forests fell in great swathes into new shallow oceans, and the warm water and the soft ooze covered them so they could not oxidise and they turned into black coal seams.

Dwarves mine for jewels: rubies, opals, sapphires, emeralds, amethysts, garnets and diamonds.

Dwarves mine for minerals: iron, tin, feldspar, lead, silver, copper and gold.

But what dwarves love best is coal.

Mining for coal is dangerous, dirty work. But in the underground forests, coal teaches the dwarves precious lessons: responsibility, attentiveness, loyalty, solidarity, honesty, strength and freedom.

And so, in the power of these hard-earned virtues, the seven dwarves lived happily enough in their little house a long way from anywhere, high in the mountains.

One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven.

And one summer evening, with the sun westering in a ruby red sky, the dwarves stomped home to their neat little house after a long day’s work – tired, hungry, and eager for beer and music. Almost before they were inside they could sense something misplaced, disrupted: a smear of mud on the mat; a couple of dry leaves adrift on the floor; the tidy stools misaligned; the spoons not perfectly straight; the rims of glasses smeared; a streak of blood on the cloth; the counterpanes rumpled. Not quite enough to call for comment or defence, but enough to make them wary, to make them glance around the house and inspect each orderly familiar detail. And so, before long, in the farthest corner of the farthest truckle bed, pressed for safety right against the wall, her face turned away from door or window, they found a little girl asleep.

There is something innocent and vulnerable about anyone watched while asleep. It induces a mood of tenderness even in the toughest, roughest characters. (It probably helped that this little girl was not the clichéd golden-haired pink child of too many romances and fairytales: her skin was as white as snow; her lips as red as fire; her hair as black as coal.) So they tiptoed away, in as much as dwarves can tiptoe, and ate their supper quietly and took their beers out into the sunny evening to drink, and they did not sing at all lest they should wake her.

She came to them as flowers came to those other forests and changed them for ever.

The next morning, after she was washed and tidied, she told them that she had run through the forest all day. ‘Go,’ the huntsman had said, ‘just go.’ Young as she was, she knew that he would rather the wild beasts kill her than do it himself. Like so many well-meaning but wage-slaved men, he was kind but not brave. That frightened her, as it should indeed, and she fled. Forests are not gentle places, never have been nor ever will. She ran blindly and in fear. By the time she found their little house she had run through thick forest for hours – her face was cut by brambles, stung by nettles; her hands and arms were raked by dead wood and grasses and briar; her face was bitten and stung and swollen-eyed and covered in mud and blood. So they did not recognise her beauty that first night, nor for a long time afterwards.

And there was the panic fear, the terror of the wild wood to soothe. Fear cramps up children’s faces, makes them look peaky and often sly, it narrows their eyes, thins their lips and sours their temper. Forest and mine are the same like this, so the dwarves knew what to do. They bade her welcome, kept the house particularly tidy and were playful with her. They took her out into the green forest to find strawberries and nuts and mushrooms. They took her to small bubbling streams and splashed in waterfalls and they taught her the prettier names of the flowers: Lords-and-ladies, Golden Rod, Herb Robert, Yellow Archangel, Solomon’s Seal, Woodruff and Goldilocks Buttercup.

“Look,” they would say.

“Take a little stick and dig and you can eat the pignuts that grow under this lacy flower.”

“Look. Suck the base of this tubular petal and see where the bees get their honey.”