Front Burner (30 page)

Authors: Kirk S. Lippold

Â

Wooden ladder made by Norfolk Naval Shipyard workers and used by MDSU-2 divers to enter upper level of main engine room 1 for the recovery efforts to find missing sailors below the waterline.

Â

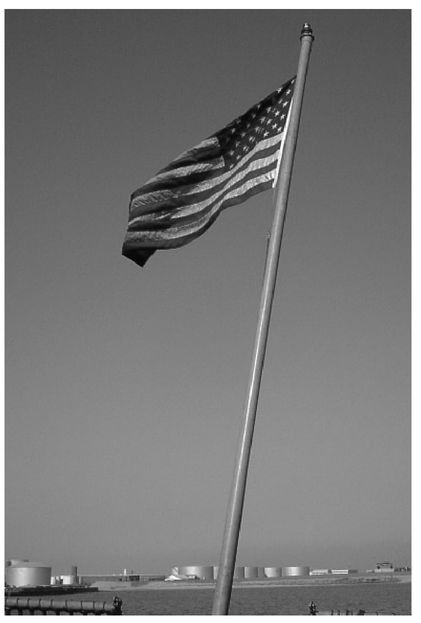

The U.S. flag that flew at full mast over the ship, lighted at night, until every sailor killed in the attack was recovered. This Battle Ensign was lowered and replaced only after the memorial ceremony to honor our seventeen fallen shipmates.

Â

The United States Navy Ceremonial Guard honors fallen members from USS

Cole

at Dover Air Force Base, Delaware, after their arrival on October 14, 2000.

Cole

at Dover Air Force Base, Delaware, after their arrival on October 14, 2000.

Â

USS

Cole

resting on docking blocks on M/V

Blue Marlin.

Cole

resting on docking blocks on M/V

Blue Marlin.

Â

The 40-by-40-foot hole in the port side of USS

Cole

. Personnel on the deck of M/V

Blue Marlin

give perspective to the size of the hole and force of the explosion.

Cole

. Personnel on the deck of M/V

Blue Marlin

give perspective to the size of the hole and force of the explosion.

Â

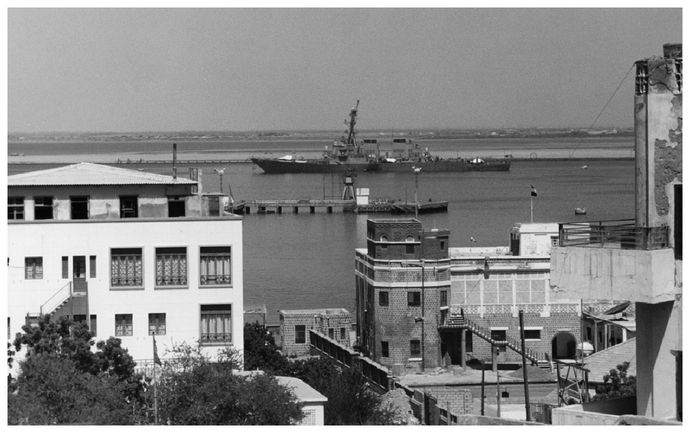

USS

Cole

at the refueling pier, as viewed from the al Qaeda safe house where covert observation and planning for a small boat attack on a U.S. warship took place.

Cole

at the refueling pier, as viewed from the al Qaeda safe house where covert observation and planning for a small boat attack on a U.S. warship took place.

Â

USS

Cole

Memorial to honor the seventeen sailors killed in the al Qaeda terrorist attack and the valiant crew who never gave up and saved their ship from sinking.

Cole

Memorial to honor the seventeen sailors killed in the al Qaeda terrorist attack and the valiant crew who never gave up and saved their ship from sinking.

A short time later, the admiral came up to speak with me. We briefly discussed a number of issues that had arisen and been dealt with over the past six days. He told me he was pleased with not only the progress of everything on the ship and the level of cooperation and support given to the crew but also the attitude of the crew in wanting to help the FBI and NCIS agents, and the divers. He then broached a sensitive subject.

He told me the crew was “tender” right now and that I needed to take their emotional state into account when making critical decisions affecting them. Coming from an admiral, this was unexpected enough; then he told me he was not sure they could “take another hit.” I held my emotions in check, but this was hard for me to swallow. My answer was very frank. The crew did not have a choice, I said; they had to be ready to take another hit. We were battle-hardened professionals and the crew needed to act like professionals. This was serious business. We had been attacked and from my vantage point, we were still in combat.

Even as we were speaking to each other, I learned later, intelligence analysts determined that the terrorist threat had increased to a point that the task force was starting to shift all personnel out of the Mövenpick and out to

Tarawa

for security reasons. While I heard and understood what Admiral Fitzgerald was telling me, inside, my feeling was: “Tender?” What did that mean? This wasn't the time for a feel-good game of patty-cake. If another attack came, I had absolute confidence in the crew. Yet here was this admiral questioning our ability to survive another hit. While not outwardly disrespectful, in my mind I was thinking, “Thank you for your advice and concern, Admiral, but please go away and give us the support we need to let us continue to get this ship ready to leave port.”

Tarawa

for security reasons. While I heard and understood what Admiral Fitzgerald was telling me, inside, my feeling was: “Tender?” What did that mean? This wasn't the time for a feel-good game of patty-cake. If another attack came, I had absolute confidence in the crew. Yet here was this admiral questioning our ability to survive another hit. While not outwardly disrespectful, in my mind I was thinking, “Thank you for your advice and concern, Admiral, but please go away and give us the support we need to let us continue to get this ship ready to leave port.”

As he prepared to leave with his entourage, Captain Hanna came up to me to thank me for having everyone on board. It was only then that I shared with him the morale-busting problem of the thefts by

Tarawa

sailors. I truly felt sorry for him as I saw the expression of shock and frustration

on his face. Evidently, there had been a number of other issues that we were not privy to regarding the support and behavior of the recently arrived amphibious ready group. He promised to look into this issue and, like the noon meal problem, fix it.

Tarawa

sailors. I truly felt sorry for him as I saw the expression of shock and frustration

on his face. Evidently, there had been a number of other issues that we were not privy to regarding the support and behavior of the recently arrived amphibious ready group. He promised to look into this issue and, like the noon meal problem, fix it.

As he was about to turn away and join up with Admiral Fitzgerald, Captain Hanna said, “Admiral Moore is going to come down tomorrow and would like to visit the ship again. Is there anything you need from him?”

This was a golden opportunity. I could ask for anything. Given how well the crew had been holding up in the heat and humidity and the stress of recovering our dead shipmates from wreckage, the satisfaction of seeing the crew embrace the psychiatric support team's mission, and who knows what else, maybe just plain hunger after subsisting on a lunch of tuna fish and crackers, I knew exactly what to request. With the impending recovery of the last of our shipmates, I told him, “Captain, I think it would be a nice treat if the crew could have some ice cream.”

Looking at me as if I must be out of my mind, he just smiled and replied, “I'll see what I can do.”

Maybe the stress was getting the better of me. Over the past several days, the Fifth Fleet chaplains and some of the psychiatric team members had given the crew the impression that they were going to be evacuated from the ship and sent home in just a few days. Whispers and rumors filled the passageways as wisps and tidbits of unfiltered information also trickled out from the support ship sailors. It seemed to the crew that everyone knew what was going to happen nextâeveryone except the captain.

This background chatter made me feel as if my crew and command were slipping away from me. My judgment and decisions were being second-guessed. Some of the task force staff were questioning how the crew was being managed in support of the FBI/NCIS investigation and evidence collection efforts; the psychiatric team leader briefed the task force commander on the crew's status without giving me any direct input into his comments; and now, the chaplains and other sailors were telling the crew they were going home as soon as a replacement crew from Norfolk, Virginia, could be organized to relieve them. There is nothing more important

than unity of command. I had a growing sense that the crew I commanded through a horrific terrorist attack was being pulled away from me from several directions without consultation or forethought about the repercussions.

than unity of command. I had a growing sense that the crew I commanded through a horrific terrorist attack was being pulled away from me from several directions without consultation or forethought about the repercussions.

These feelings now led to the most significant meltdown of my career.

Two of my officers sheepishly approached me midafternoon with some disturbing information. Command Master Chief Parlier had privately met with the chief petty officers. They had urged him to approach me about letting the crew go home as soon as possible. As a group, many of them had talked themselves into believing the ship was unsafe, and that they needed to get out of there. During that discussion, my officers said, the Master Chief changed his view from support for me to support for them. He, too, also began to question the structural integrity of the ship. The chiefs had also expressed their fears about the known and growing threat of another attack. To add fuel to the fire, the Master Chief had allegedly questioned my judgment in understanding the risk of a follow-on attack and ability of the crew to respond effectively.

Other books

Summon Up the Blood by R. N. Morris

Shadow Ritual by Eric Giacometti, Jacques Ravenne

The Visible Filth by Nathan Ballingrud

With Fate Conspire by Marie Brennan

Blood Tribute (The Lucas Gedge Thrillers Book 1) by Andy Emery

Demon Rock by Stephen Derrian

Unforgettable by von Ziegesar, Cecily

The Hungry Season by Greenwood, T.

Proof of Heaven by Mary Curran Hackett

Future Dreams by T.J. Mindancer