Full Moon (20 page)

“Chamber of initiation—font of baptism!” said Wu Tu, spluttering and

laughing. “She got into this, I bet you! Could she get in? Was she too big?

Have some champagne, it tastes good in a bath!”

Blair glanced at the Chinese girl. Her back toward him, she was emptying

one of the hampers, on the floor, almost straight between him and the low,

dark entrance. It was velvet-dark there—a black square blot on a wall

stained dark-red by the lantern-light. But something in the blackness moved.

His eye: caught it. He watched. A man’s face, spectral, almost darker than

the darkness, gradually took form.

For a moment he thought it was Taron Ling returned to life and his skin

crept up his: spine, but he knew that was nonsense. He decided it must be

one. of the men they had left behind in the other tunnel, so he looked for

the revolver in the crack in the wall. It had vanished. But the man’s face

was still there, very low, near the edge of the dark, in the mouth of the

low, square opening.

He leaped suddenly out of the cistern, with the red light like blood on

his wet skin, and sent the Chinese girl sprawling. He grabbed the revolver

from the hamper, where she had half-hidden it under napkins. He had no

cartridge now; it was in his pocket.

He knew he was a perfect target in the lantern-light—knew, too, that

the Chinese girl and Wu Tu were behind him and not likely to neglect an

opportunity. So he was quick. He reached the opening in three leaps—

stooped—stared, and froze motionless. There was a finger on the face’s

lips. There was a signal—a very low whisper. Chetusingh, haggard,

wild-eyed. and corpse-like, but unmistakably Chetusingh, crawled backward

until he became one with the darkness and vanished.

“Taron Ling?” demanded Wu Tu from the cistern.

“No,” he answered. “Nerves. I thought I saw him.”.

“Why did you whisper then? I heard you.”

“If you want to know,” he said, “I was praying. I’m chattering

nervous.”

She climbed out. “Have some champagne.”

Red light glowed all over her.

“You look like a devil in hell!” he said laughing. The laugh sounded

nervous and seemed to convince her. He made a show of recovering

self-control—pulled out serviettes from the hamper—tossed her

several of them —rubbed himself dry with two others, and put his

sweat-wet tunic on again. Even that disgusting anticlimax could not lower his

spirits now. Chetusingh had told him Henrietta was not in immediate danger.

He had time for what the commissioner called “facts, not fireworks.” He

dressed swiftly and reloaded the revolver.

There was a sudden pop, then, like a cannon going off. The Chinese girl

poured champagne into a big cut-glass tumbler. Wu Tu gulped half of it down.

That at any rate was not poisoned. Blair took the tumbler from her hand and

drank the other half. It was warm, but good dry wine; it found his nerves and

seemed to pour along them.

“What next?” he demanded.

“Food,” said Wu Tu, who was wrapping her sari around her.

Good? Bad? Those are relative. I have not seen one without

the other; they are two sides of the same thing, and the thing is integrity,

which has no opposite. Treachery may have integrity and may do good, as when

a traitor betrays a devil. Integrity may ruin thousands, as when nations go

to war for a principle, which may be right or wrong. The wrong may have the

more integrity! Integrity is a thing in itself. It is a middle way between

good and evil. It serves best him who has it, but he has it not unless he use

it. And he has it not if he should try to use it for a momentary profit.

Good? Bad? Neither of those affects the balance of the Infinite. But

Integrity? That is the length, breadth, depth, weight, essence and proof of

Character, which is Quality. And Quality is the goal of evolution. Aim ye at

that, and ye aim at eternal life.

—From the Ninth (unfinished) Book of Noor Ali.

THE food was warm, unappetizing tinned stuff, hard-boiled

eggs, fruit, and some leathery looking chupatties. Eggs and fruit might have

been drugged. That was even probable. Wu Tu tried to force them on him, so

Blair chose a tin of sardines, which he could open for himself; they were

unappetizing without bread, but the chupatties were a too obvious trick. He

refused more champagne; there had been time for the Chinese girl to doctor

what remained in the bottle. Wu Tu drank none and she did not order a second

bottle to be opened. She ate seated on one of the hampers, looking like the

devil in the red light, with her hair wet and the Chinese girl trying to

rearrange it.

Blair walked up and down examining the golden objects on the low hewn

shelf. He was in no hurry now—none whatever. Impatience might slam the

door on a secret that seemed on the verge of revealing itself. The next move

should be Chetusingh’s. But Wu Tu might have a card up her sleeve, and the

thing to do was to discover that, if possible without letting her suspect its

discovery. She was talkative, attempting to conceal excitement, and a bit too

evidently eager to feel her way toward an exchange of confidences.

“Guess the value of that gold, Blair. It is gold. Every bit of it’s gold.

But it’s hard. It can’t even be marked with a hammer.”

“How do you know it’s gold?” he demanded. He tapped the barrel of the

revolver against a molded, massive thing that his utmost strength could not

move; it was in the form of two big pythons coiled on one another. It sounded

solid.

“When it’s melted the bullion merchants buy it as gold,” she answered.

“Two or three times’ melting takes away its hardness, but the difficulty is

to get it out of here without people knowing. All the small stuff has gone,

except that bowl that we use to carry water. Why did you spill the water? Did

you think I’d poison you? I need you.”

“Who took all the small stuff?”

“Zaman Ali. There were eighteen gold blocks and fifty figurines; he melted

all but two gold blocks that General Frensham took, and one figurine that I

have. I believe you saw it.”

“How do you know Frensham took them?”

“Oh, I know lots of things. One of the two that he took found its way into

the police commissioner’s hands in Bombay. Taron Ling tried to get it. His

magic wouldn’t work because the commissioner hasn’t the right sort of

imagination. Two of Zaman Ali’s men recovered the other block from Frensham’s

suitcase at the time when he disappeared. Zaman Ali shot those thieves last

night. They swore it had been stolen from them and he knew that was a lie,

but he was so afraid of magic that he couldn’t wait for Taron Ling to make

them tell where they’d hidden it. Now I suppose it’s lost forever.”

To get her to talk, and to gain time was Blair’s immediate problem. If he

appeared not particularly interested, she might reveal more in an effort to

get his attention. So he took one of the red-glazed lanterns and examined the

golden objects on the hewn shelf. To become competent in his profession he

had had to make himself familiar with Indian religions, but these things

reminded him of no religion he had ever studied.

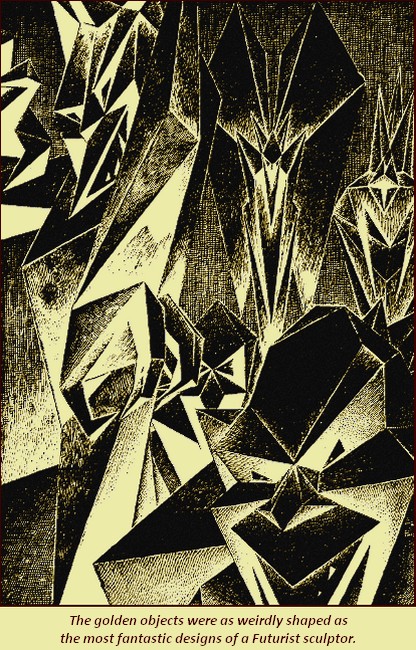

There were forty-nine pieces. They might be idols or religious symbols.

They excited imagination. But except for that one example of coiled serpents,

they suggested nothing he had ever seen and no answer to the riddle they

presented. They were not Hindu. They were not Buddhistic. They were as

weirdly-shaped as the most fantastic designs of a Futurist sculptor in

rebellion against three-dimensional limitations. They had a motive;, that

much was obvious. They had rhythm. But neither rhythm nor motive was

intelligible.

“How long have you known of this place?” he demanded.

“Two years.” Wu Tu was watching him intently, but he behaved as if unaware

of that. Her attitude and expression were lynx-like. She appeared to be

judging his mood and her chance. She went on, “Frensham knew about it

first—I don’t know how. long ago. He was only a,major when he met that

Bat-Brahmin who calls himself the Guardian of Gaglajung. Somehow he persuaded

the Bat to talk. Most Bats are drunkards. Probably he gave him whisky. That

Bat is a superstitious fool who only knows the legend. He has never dared to

enter the caverns. He has never been into the tunnel. Generations of

Bat-Brahmins have known of this place without ever daring, to enter it.

“The hermit guided Frensham in—and went mad. Did you see him?

Frensham took two of the blocks, which was all he could carry. He meant to

return for the others, but the Bat-Brahmin threatened to have him broke out

of the army for sacrilege. That was no joke either. He could have done it.

Frensham didn’t dare show those blocks to anyone. But I found out about

them.”

She paused, weighing the effect of her words. Blair decided she needed

some encouragement. He set the lantern down and walked slowly toward her.

“You’re a wonderful woman,” he said with admiration in his voice.

Her eyes betrayed a hesitating triumph. She was not quite sure of him. But

she said something in Chinese, and the Chinese girl withdrew to a little

distance, picking up the lantern he had set down and putting it back beside

the two others. That produced a shadow into which she sidled, Blair almost

lost sight of her; but with the corner of his eye he could just catch the

color of her daffodil pyjamas. There was treachery coming.

“You’re a great woman,” he repeated. He was standing almost over Wu Tu,

looking down at her.

“No, not great yet. I propose to be,” she answered. “Will you help me to

it?”

“You need my help? Rot!” he retorted. “How about helping me? You said you

would. You’re unbeatable. How do you do it? How did you discover all

this?”

The Chinese girl had moved away from the lanterns. She was hovering behind

him now, and he had to watch Wu Tu’s eyes. The water pouring into and out of

the cistern filled the place with sound; his ears had grown accustomed to it,

but he had to depend on his ears and listen to Wu Tu at the same time,

without betraying his alertness.

“Frensham’s wife died eighteen years ago,” said Wu Tu.

“Well? What of it?”

“Men need women.”

“I get you.”

“Frensham is a learned simpleton,” she went on. “He was learned and

intelligent enough to know he had stumbled on a priceless secret if he could

only interpret it. He was too reverent to play the vandal, and too afraid for

his own reputation to admit he had trespassed into a forbidden sanctuary. But

he was jealous, too. He didn’t want to share the secret with

anyone—jealous and simple-minded. He wanted somebody to open those

blocks without injuring the contents. They’re hollow and he suspected they

contain tablets or something like that, with some kind of writing on them.

Why he trusted Dur-i-Duran Singh of Naga Kulu I can’t tell you; I would

sooner trust a cobra. But I think Dur-i-Duran Singh had done him some

financial favors. Unbusinesslike people such as Frensham are easily

psychologised in that way.

“He asked Dur-i-Duran Singh to find him an expert metallurgist who could

be trusted to keep secrets. Dur-i-Duran Singh consulted me. I got a clever

girl to entertain Frensham and find out the secret. Frensham is a fatherly

old thing, and he liked to talk to her. He didn’t say much, but he told her

enough to make me more than interested.”

“Drunk?” Blair asked.

“No. Couldn’t make him drunk. He’s abstemious. Besides, some men don’t

talk when they’re drunk. That isn’t the best way.”

Blair changed position until through the side of his eye he could see the

Chinese girl standing ten feet away from him quite still; she appeared to be

interested in the red light on the running water. Wu Tu continued:

“It was then that Zaman Ali came in, because I needed someone capable of

tracing Frensham’s movements backward to all the places he had visited on

leave or in the course of duty. Zaman Ali was a greedy thief and a bully, but

there was no one better for the purpose. He back-tracked Frensham to

Gaglajung.

“With a nose for loot like Zaman Ali’s it wasn’t long before he suspected

the Bat-Brahmin and guessed where to look. But the Bat-Brahmin proved

difficult—denied everything— threatened to raise a riot and bring

police on the scene if Zaman Ali dared to trespass. Bribery didn’t work. So I

consulted Dur-i-Duran Singh again, and he sent Taron Ling. Magic terrified

the Bat. Taron Ling made him see elementals and hear voices. Then he

hypnotised the hermit. But even Taron Ling couldn’t get into the caverns. It

was I who did that.”

Blair felt a prick on the back of his right hand. He bit and sucked it

instantly. His left hand—his eyes were watching Wu Tu’s and he had seen

her signal—moved with the speed of a knock-out punch and seized the

Chinese girl’s right wrist, twisting, twisting. He did not dare to take his

eyes off Wu Tu. He twisted the girl’s wrist unmercifully, but she neither

screamed nor let go the thin-bladed dagger. She writhed like a snake and

tried to reach Wu Tu, who jumped up and snatched at the weapon. Blair sent Wu

Tu sprawling. Then he rapped the girl’s knuckles with the barrel of the

revolver until she dropped the dagger. Kicking the dagger along the floor in

front of him to keep it out of Wu Tu’s reach, he picked up the girl then and

dumped her into the cistern, where he held her head under so long that Wu Tu

screamed at him: