Full Tilt

Authors: Dervla Murphy

Ireland to India with a Bicycle

‘She avoided wolves (animal and human), floods, robbery, had three ribs broken in a brawl in an Afghan bus; waded across an ice torrent, hugging a cow … suffered extremes of heat and cold, ate everything, liked almost everybody.’

Homes and Gardens

‘This vivid journal … would have delighted Cervantes with its almost incredible surprises: a valley full of birds the size of butterflies and butterflies as big as robins; a village where the cattle eat apricots and the villagers eat clover … Somewhere between Kabul and Jalalabad, she thought she was dreaming when she awoke from a roadside nap to find that nomads had raised a tent over her to shield her from the sun.’

The New Yorker

‘I don’t know when I’ve enjoyed the account of a journey more. A great part of the enchantment of her book is that it is so good humoured and so funny. I laughed … and learned a good deal … one follows her with pleasure … a brave, intelligent, rare and amusing human being.’

Margaret Lane

‘A journey fraught with incalculable hardships and perils. It is unexpected, but then everything Dervla Murphy does is unexpected … an enchantment that holds the reader as engrossed as would an exciting thriller.’

Irish Independent

‘Warmly described, and with a lack of self-regard that immediately endears her to the reader.’

Sunday Times

‘Punctures, broken ribs, hornets and scorpions notwithstanding, it was a high old time between Miss Murphy and her Islamic hosts … her book is sensible, warm-hearted, unfinicky.’

The Observer

Ireland to India with a Bicycle

DERVLA MURPHY

To the peoples of

Afghanistan and Pakistan,

with gratitude for their hospitality,

with admiration for their principles

and with affection for those who befriended me

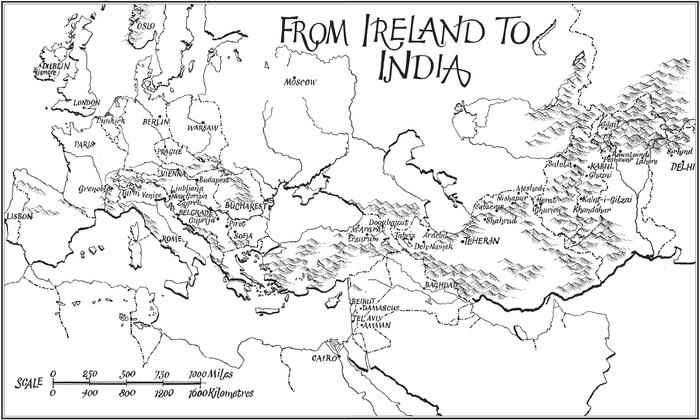

On my tenth birthday a bicycle and an atlas coincided as presents and a few days later I decided to cycle to India. I’ve never forgotten the exact spot on a hill near my home at Lismore, County Waterford, where the decision was made and it seemed to me then, as it still seems to me now, a logical decision, based on the discoveries that cycling was a most satisfactory method of transport and that (excluding the USSR for political reasons) the way to India offered fewer watery obstacles than any other destination at a similar distance.

However, I was a cunning child so I kept my ambition to myself, thus avoiding the tolerant amusement it would have provoked among my elders. I did not want to be soothingly assured that this was a passing whim because I was quite confident that one day I

would

cycle to India.

That was at the beginning of December 1941, and on 14 January 1963, I started to cycle from Dunkirk towards Delhi.

The preparations had been simple; one of the advantages of cycling is that it automatically prevents a journey from becoming an Expedition. I already possessed an admirable Armstrong Cadet man’s bicycle named Rozinante, but always known as ‘Roz’. By a coincidence I had bought her on 14 January 1961, so our journey started on her second birthday. This was ideal; we were by then a happy team, having already covered thousands of miles together, yet she was young enough to be dependable. The only preparation Roz needed was the removal of her three-speed derailleur gear, which I reckoned would be too sensitive to survive Asian roads. Apart from the normal accessories – saddle-bag, bell, lamp and pump – she carried only pannier-bag holders on either side of the back wheel. Unloaded she weighs

thirty-seven

pounds and at the start of the journey she was taking twentyeight pounds of kit while I carried another six pounds in a small knapsack. (A list of kit is given on page 231.) Before leaving Ireland, four spare tyres had been posted ahead to various British Embassies, Consulates and High Commissions en route; Roz takes 27½" x 1¼" tyres, which are not a standard measurement abroad.

In London, at the end of November 1962, I obtained without difficulty visas for Yugoslavia and Bulgaria; I planned to get my visas for Persia in Istanbul and for Afghanistan in Teheran. During the same visit to London I endured vaccinations and inoculations for smallpox, cholera, typhoid and yellow-fever – the latter in case I decided to return from India via Africa.

Most of the following month was spent bending over maps bought through the AA in Dublin, working out the distances between towns which had intoxicatingly improbable names. I calculated that it was 4,445 miles from Dunkirk to Peshawar, and by New Year’s Eve I could have told you without hesitation where I planned to be on any given date between 14 January and 14 May, when I hoped to arrive in Peshawar. The object of this exercise was to ensure that my mail – sent care of the British Council offices en route – would not miss me; nor did it, despite many inevitable changes in my original plans.

In the intervals between mapping I took myself off to remote areas in the mountains around Lismore and practised firing and reloading my ·25, the purchase of which had recently been achieved with the full and rather awe-struck co-operation of the local police. My friends regarded this purchase as so much adolescent melodrama on my part but fortunately I ignored their criticisms and stuck to my gun, though its presence in the right-hand pocket of my slacks – where I habitually carried it to accustom myself to the presence of a loaded weapon – frightened me considerably more than it did anyone else. Yet within a month of leaving home the seemingly childish game of whipping it out of my pocket and flicking up the safety catch was fully justified.

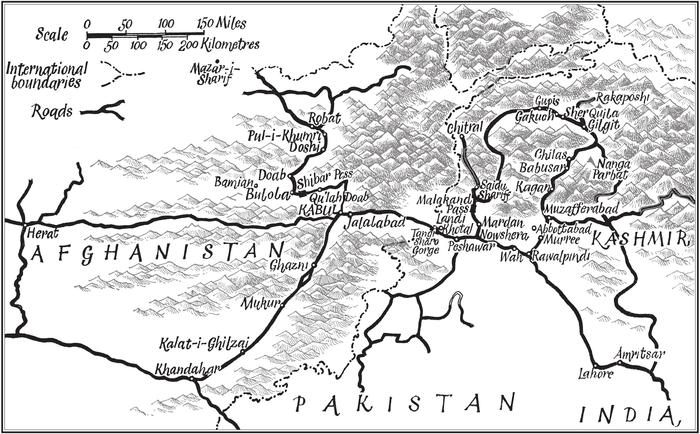

I arrived in Delhi on 18 July 1963, almost six months after leaving Ireland. People with mathematical brains are always anxious to know exactly how many miles I had cycled by then and what my daily

average was. Unfortunately gadgets for measuring mileage do not function on Asian roads, so I can only estimate vaguely that Roz and I covered about three thousand miles, including our detours to Murree and Gilgit. From this the mathematically inclined can easily calculate our average daily mileage, but their findings would be slightly misleading, because there were so many days when we did not cover even a mile together. Our shortest run was, I think, nineteen miles, and our longest 118 miles, but I reckon that our average on a normal cycling day was between seventy and eighty miles.

This is perhaps the moment to contradict the popular fallacy that a solitary woman who undertakes this sort of journey must be ‘very courageous’. Epictetus put it in a nutshell when he said, ‘For it is not death or hardship that is a fearful thing, but the fear of death and hardship.’ And because in general the possibility of physical danger does not frighten me, courage is not required; when a man tries to rob or assault me or when I find myself, as darkness is falling, utterly exhausted and waist-deep in snow halfway up a mountain pass, then I

am

afraid – but in such circumstances it is the instinct of

self-preservation

, rather than courage, that takes over.

For the first two months of the trip I struggled hard to keep my four closest friends informed of my progress through letters but the effort was too much; so from Teheran onwards I adopted the diary-keeping method used by most travellers and sent instalments home whenever a reliable-looking post office appeared en route. My friends circulated these instalments amongst themselves, the last on the circuit line storing the manuscript away for future reference. This book is the ‘Future Reference’.

Apart from burnishing the spelling and syntax, which are apt to suffer when one makes nightly entries whether half asleep or not, I have left the diary virtually unchanged. A few very personal or very topical comments or allusions have been excised, but the temptation to make myself sound more learned than I am, by gleaning facts and figures from an encyclopaedia and inserting them in appropriate places, has been resisted. For this reason the narrative which follows will be seen to suffer from statistic-deficiency; it only contains such

information as any traveller might happen to pick up from day to day along my route.

After arriving in Delhi I worked for six months with the Tibetan refugees in northern India and then enjoyed a few more treks with Roz in the Himalayas and in south-west Nepal, before submitting to the degradation of flying home on 23 February 1964, with a dismantled Roz by my side as ‘personal effects’.

My thanks go in many directions: to the British and American consular officials in those countries where Ireland is not diplomatically represented, who adopted and cared for me as though I were their own; to the scores of individuals and families in every country on my route whose boundless hospitality taught me that for all the horrible chaos of the contemporary political scene this world is full of kindness; to the chance friends I made in odd places, whose names I never knew or have forgotten but whose companionship made a sometimes lonely journey much more pleasant; and last, but certainly not least, to Daphne Pearce, who suggested the title and gave invaluable help in editing the manuscript; to Patricia Truell, who compiled the index and guided me through the ordeal of correcting my first proofs; and to my other friends in Ireland, who loyally and patiently read over 200,000 words in an execrable hand and whose interest in my experiences was both the inspiration and the reward of keeping this diary.

For my part I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move, to feel the needs and hitches of our life more nearly, to come down off the feather-bed of civilization and find the globe granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints.

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON