Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students (33 page)

Read Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students Online

Authors: Louise Lewis

BOOK: Fundamentals of Midwifery: A Textbook for Students

12.11Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Change of role and responsibilities

Change in employment status

Loss of income

Isolation

Physical and mental exhaustion

Emotional lability

Feeling overwhelmed caring for a new baby

Loss of control

Abandonment

Changes in self/body image

Physical impact on body

Loss of identity

Vulnerability

Feeling unprepared

Sleep disturbances/deprivation

Loss of independence

Table 4.2

Differences between baby blues and postnatal depression

Baby blues

Baby blues

Postnatal depression

Transient low mood – peaks 4–5 days postnatally, usually disappears by 4 weeksCan occur at any time in the early or late postnatal periodWomen may experience:Does not usually require interventionWomen may experience:Requires healthcare interventions (see Chapter 13: ‘Perinatal mental health’ for further detail)(NICE 2006)

Table 4.2

Differences between baby blues and postnatal depression

Baby blues

Baby bluesPostnatal depression

Transient low mood – peaks 4–5 days postnatally, usually disappears by 4 weeksCan occur at any time in the early or late postnatal periodWomen may experience:Does not usually require interventionWomen may experience:Requires healthcare interventions (see Chapter 13: ‘Perinatal mental health’ for further detail)(NICE 2006)

fatigue

feeling overemotional, tearfulness

mood swings

low spirits,

anxiety,

forgetfulness and muddled thinking

depression

confusion

headache

insomnia irritability

emotional lability

an inability to experience pleasure

depressed mood

loss of interest or pleasure

significant increases or decreases in appetite

insomnia or hypersomnia

psychomotor agitation or retardation

fatigue or loss of energy

feelings of worthlessness or guilt

diminished concentration

recurrent thoughts of suicide72

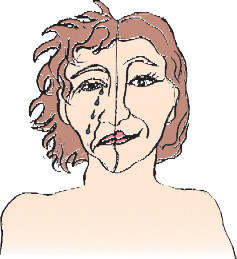

Baby blues and postnatal depression

It is common for women to experience the‘baby blues’, a fluctuation of emotions and low mood (Table 4.2). This emotional phenomenon is transitory, commencing between 4–5 days postna- tally and lasting for less than a month. Postnatal depression (PND) in contrast, differs from the baby blues in that it can occur at any time during the postnatal period including up to one year postnatally and has a significant impact on the women’s physical and psychological recovery following birth (NICE 2006); with an incidence of 10–15% (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2014). A smaller percentage of women will report symptoms commensurate with PTSD, which are often mistaken for PND and thus the treatment process may not fit the disease (Peeler et al. 2013) (see Chapter 13: ‘Perinatal mental health’, where both PND and PTSD will be discussed inmore detail).Other factors influence women’s psychological status and may contribute to psychological distress such as difficulty breastfeeding, coping with crying, unsettled babies and fatigue (Taylor and Johnson 2010). However, this is not inevitable and midwives can contribute to maternal psychological wellbeing by giving practical support relating to infant feeding and building women’s confidence in their mothering skills (Marshall et al. 2007).Some women will attempt to mask depression (see Figure 4.2); the ‘rigging’ of responses to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale due to difficulty expressing ‘maternal ambivalence’ and desires to conceal their actual reality of motherhood has been demonstrated (Miller 2011). One explanation may be the concept of ‘blissful parenthood’, still embedded in society’s expec- tations of motherhood, which can relegate women with PND to the status of ‘bad mother’ (Buultjens and Liamputtong 2007). Women have reported feeling that they should be able to cope with motherhood; the inability to cope conflicting with their pre-birth perception of ‘self’ as a competent woman (Buultjens and Liamputtong 2007).Relationships can be critical in terms of psychological wellbeing, yet Bateman and Bharj (2009) highlight the impact of the birth of a baby on marital satisfaction and authors have found a correlation between maternal and paternal PND (Goodman 2004; Ramchandani et al. 2005).

73

73

Figure 4.2

Some women may mask their true feelings in motherhood. Source: Reproduced with permission from P. Alexander.This has implications on the quality of the family relationship if both parents are depressed. Women suffering psychological distress describe support from other mothers as invaluable becauses it normalises the emotional lability of the postnatal experience and affords permission to express negative emotions (Darvill et al. 2010). The role of the midwife can also play a critical role in supporting women through periods of emotional turmoil of psychological distress, as discussed later in this chapter.The postnatal period is an emotional journey, where women adapt to the role and demands of motherhood and renegotiate their identity. A labile, emotional journey is both inevitable and normal and evidence illustrates that improved postnatal physical recovery is paralleled with an improved psychological profile (Jomeen and Martin 2008a); indeed a study by McKenzie and Carter (2013) found that the transition to parenthood can result in improvements in psychologi- cal distress and mental health once the immediate postnatal period is traversed. Some women, however, will enter the postnatal period in a vulnerable psychological state which began ante- natally or during birth. Kitzinger (2012) notes that women who felt powerless in labour report a sense of loss, of having missed out on the experience of birthing their babies and will report feelings of ‘failure’ which can impact self-esteem and mental wellbeing.

Summary

The midwife will be involved in caring for women within normal physiological parameters of childbearing who can bring their psychological pathology to pregnancy. Most women will go through a range of differing and undulating emotions in pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period and that is normal and expected. Midwives have a key role to play in supporting women through their emotional journey being mindful of the myriad of challenges they may experi- ence. While the midwife is not expected to be a psychologist/psychiatrist or counsellor, aware- ness and recognition of normal emotional reactions versus abnormal are critical.

Women and midwives: relationships and communication

One of the most characterising aspects of being human is that they are social, affected by the

74 presence of other people, have strong needs to affiliate and form relationships with others and behave in certain ways towards members of their own and other groups. Amongst others, oneof a person’s motives for affiliation is anxiety reduction and information seeking (Hewstone et al. 2005). Therefore, a positive relationship with the midwife can be critical to women.Mavis Kirkham writes

74 presence of other people, have strong needs to affiliate and form relationships with others and behave in certain ways towards members of their own and other groups. Amongst others, oneof a person’s motives for affiliation is anxiety reduction and information seeking (Hewstone et al. 2005). Therefore, a positive relationship with the midwife can be critical to women.Mavis Kirkham writes

. . . The midwife relationship of maternity services: for many women that relationship is the service . . .

(Kirkham 2010, p. xiii)When a relationship is ‘done well’ it undoubtedly benefits all parties and enhances feelings of self-worth, wellbeing and satisfaction. Poor relationships on the other hand can be damaging to women in terms of self-esteem, feelings of control and quality of experience and for midwives in terms of job satisfaction and emotional labour.

The psychological importance of the woman–midwife relationship

For women

Childbearing is a complex experience. Midwives need to both understand this complexity, but also be able to build effective relationships with women while they are in pain, distracted, anxious and fearful or disadvantaged in some way (Raynor and England 2010) and offer the support women need.The stimuli experienced by a woman through pregnancy, labour, birth and in making the transition to motherhood, are exceptional. Women are required to appraise emotion producing events within a constantly changing environment, which is largely driven by psychological and biological components. It is also strongly influenced, however, by social conditions, which are created through the presence of those who surround the woman at that time and the relation- ships that are formed within that context.This highlights the significant role that the midwife has in creating women’s childbearing context and experience. While most women appraise the events around childbirth satisfactorily and make the transition to motherhood smoothly, the successful dealing with and processing of maternal emotions is critical. White (2005) suggests that failure to process emotions success- fully could explain the emergence of conditions such as PND depression or post-birth traumatic stress. Little direct information exists about how interaction with care givers might support emotional processing

per se

, but evidence does suggest that how the midwife deals with emotion can have a significant impact on women. This can be in terms of women’s decision- making (Edwards 2009) and level of anxiety at the time (Byrt et al. 2008; Hunter et al. 2008), but it is also suggested that the midwife–woman relationship is an important aspect of satisfaction. This is linked to the level at which women feel involved in and have some control over, the process of their care (Slade et al. 1993; Tinkler and Quinney 2001). Evidence suggests that a woman’s feelings of being ‘in control’ are impacted on by the positive attitudes of the midwives caring for them, information giving during pregnancy and labour and being able to make and be included in decision-making during labour (Gibbins and Thomson 2001; see Chapter 3: ‘Antenatal midwifery care’, where decision-making is examined in greater depth). This could be defined as supportive care, which has been identified both qualitatively and quantitatively as an important variable with regard to more positive experiences for women (Waldenström et al. 2004; Kitzinger 2006; Kirkham 2010). Conversely, reduced levels of control and satisfaction havebeen linked to more enduring negative psychological consequences for women, such as PTSD and depression (Czarnocka and Slade 2000; Nilsson and Lundgren 2009) and poorer adjustment to motherhood (Dimatteo and Khan 1997).

The psychological impact on women of the way that midwives interact with them seems clear, but equally important is how midwives manage their own emotions.

The psychological impact on women of the way that midwives interact with them seems clear, but equally important is how midwives manage their own emotions.

For midwives

75Emotional work is a feature of all human relationships and is about dealing with our own and other people’s emotions. Interactions between midwives and women as already suggested are social encounters, but ones that often happen in non-ordinary circumstances and involve inti- mate procedures and personal information. Midwives need to manage their feelings so that they are appropriate to the situation they are in (Deery and Hunter 2010); however this can be at cost to the worker who must maintain a professional demeanour (Edwards 2009). The require- ment for midwives to give the right emotional response to the clinical situations that emerge has been reported in several studies as challenging and stressful (Deery and Kirkham 2006; 2007; Earle et al. 2007). Billie Hunter (2006) writes about four key situations which midwives encounter; these include balanced exchanges, rejected exchanges, reversed exchanges and unsustainable exchanges. The latter three exchanges require high levels of ‘emotion work’ by the midwife, whilst balanced exchanges, where there is ‘give and take’ on both sides, are more emotionally rewarding for the midwife. This highlights the clear significance of positive relation- ships for midwives as well as women, which can happen even in the face of adverse outcomes where a supportive relationship has enabled the situation to be as good as possible in the cir- cumstances (Deery and Hunter 2010).

. . . When a meaningful relationship is created, emotion work is not experienced as hard work but is something akin to a gift . . .

(Bolton in Deery and Hunter 2010)Often, however, midwives employ strategies to remain detached. Ruth Deery (Deery and Hunter 2010) describes:

Technical detachment:

The fragmentation of a woman’s care into manageable tasks in order to maximise the midwife’s control of clinical decision-making.

Emotional detachment:

Aimed to protect against over-involvement with women, often engaged in times of high anxiety, which might have short-term benefits for the midwife.Whilst these types of strategies are most often engaged to enable midwives to cope, they inevitably create boundaries and distance from women. Strategies also include stereotyping women as a way of discounting needs that cannot be met (Deery and Kirkham 2007). The problem with such approaches is that they lead to a task-oriented, de-personalised approach, low morale, stress and burn-out (Hunter 2004; Deery and Kirkham 2007). Those relationships that are emotionally positive, underpinned by mutuality, trust and genuineness contribute not only to job satisfaction, but also the midwives sense of self, as a person not a role (McCourt and Stevens 2009). Where midwives keep their ‘

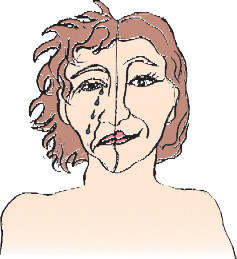

Baby blues and postnatal depression

It is common for women to experience the‘baby blues’, a fluctuation of emotions and low mood (Table 4.2). This emotional phenomenon is transitory, commencing between 4–5 days postna- tally and lasting for less than a month. Postnatal depression (PND) in contrast, differs from the baby blues in that it can occur at any time during the postnatal period including up to one year postnatally and has a significant impact on the women’s physical and psychological recovery following birth (NICE 2006); with an incidence of 10–15% (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2014). A smaller percentage of women will report symptoms commensurate with PTSD, which are often mistaken for PND and thus the treatment process may not fit the disease (Peeler et al. 2013) (see Chapter 13: ‘Perinatal mental health’, where both PND and PTSD will be discussed inmore detail).Other factors influence women’s psychological status and may contribute to psychological distress such as difficulty breastfeeding, coping with crying, unsettled babies and fatigue (Taylor and Johnson 2010). However, this is not inevitable and midwives can contribute to maternal psychological wellbeing by giving practical support relating to infant feeding and building women’s confidence in their mothering skills (Marshall et al. 2007).Some women will attempt to mask depression (see Figure 4.2); the ‘rigging’ of responses to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale due to difficulty expressing ‘maternal ambivalence’ and desires to conceal their actual reality of motherhood has been demonstrated (Miller 2011). One explanation may be the concept of ‘blissful parenthood’, still embedded in society’s expec- tations of motherhood, which can relegate women with PND to the status of ‘bad mother’ (Buultjens and Liamputtong 2007). Women have reported feeling that they should be able to cope with motherhood; the inability to cope conflicting with their pre-birth perception of ‘self’ as a competent woman (Buultjens and Liamputtong 2007).Relationships can be critical in terms of psychological wellbeing, yet Bateman and Bharj (2009) highlight the impact of the birth of a baby on marital satisfaction and authors have found a correlation between maternal and paternal PND (Goodman 2004; Ramchandani et al. 2005).

73

73Figure 4.2

Some women may mask their true feelings in motherhood. Source: Reproduced with permission from P. Alexander.This has implications on the quality of the family relationship if both parents are depressed. Women suffering psychological distress describe support from other mothers as invaluable becauses it normalises the emotional lability of the postnatal experience and affords permission to express negative emotions (Darvill et al. 2010). The role of the midwife can also play a critical role in supporting women through periods of emotional turmoil of psychological distress, as discussed later in this chapter.The postnatal period is an emotional journey, where women adapt to the role and demands of motherhood and renegotiate their identity. A labile, emotional journey is both inevitable and normal and evidence illustrates that improved postnatal physical recovery is paralleled with an improved psychological profile (Jomeen and Martin 2008a); indeed a study by McKenzie and Carter (2013) found that the transition to parenthood can result in improvements in psychologi- cal distress and mental health once the immediate postnatal period is traversed. Some women, however, will enter the postnatal period in a vulnerable psychological state which began ante- natally or during birth. Kitzinger (2012) notes that women who felt powerless in labour report a sense of loss, of having missed out on the experience of birthing their babies and will report feelings of ‘failure’ which can impact self-esteem and mental wellbeing.

Summary

The midwife will be involved in caring for women within normal physiological parameters of childbearing who can bring their psychological pathology to pregnancy. Most women will go through a range of differing and undulating emotions in pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period and that is normal and expected. Midwives have a key role to play in supporting women through their emotional journey being mindful of the myriad of challenges they may experi- ence. While the midwife is not expected to be a psychologist/psychiatrist or counsellor, aware- ness and recognition of normal emotional reactions versus abnormal are critical.

Women and midwives: relationships and communication

One of the most characterising aspects of being human is that they are social, affected by the

74 presence of other people, have strong needs to affiliate and form relationships with others and behave in certain ways towards members of their own and other groups. Amongst others, oneof a person’s motives for affiliation is anxiety reduction and information seeking (Hewstone et al. 2005). Therefore, a positive relationship with the midwife can be critical to women.Mavis Kirkham writes

74 presence of other people, have strong needs to affiliate and form relationships with others and behave in certain ways towards members of their own and other groups. Amongst others, oneof a person’s motives for affiliation is anxiety reduction and information seeking (Hewstone et al. 2005). Therefore, a positive relationship with the midwife can be critical to women.Mavis Kirkham writes. . . The midwife relationship of maternity services: for many women that relationship is the service . . .

(Kirkham 2010, p. xiii)When a relationship is ‘done well’ it undoubtedly benefits all parties and enhances feelings of self-worth, wellbeing and satisfaction. Poor relationships on the other hand can be damaging to women in terms of self-esteem, feelings of control and quality of experience and for midwives in terms of job satisfaction and emotional labour.

The psychological importance of the woman–midwife relationship

For women

Childbearing is a complex experience. Midwives need to both understand this complexity, but also be able to build effective relationships with women while they are in pain, distracted, anxious and fearful or disadvantaged in some way (Raynor and England 2010) and offer the support women need.The stimuli experienced by a woman through pregnancy, labour, birth and in making the transition to motherhood, are exceptional. Women are required to appraise emotion producing events within a constantly changing environment, which is largely driven by psychological and biological components. It is also strongly influenced, however, by social conditions, which are created through the presence of those who surround the woman at that time and the relation- ships that are formed within that context.This highlights the significant role that the midwife has in creating women’s childbearing context and experience. While most women appraise the events around childbirth satisfactorily and make the transition to motherhood smoothly, the successful dealing with and processing of maternal emotions is critical. White (2005) suggests that failure to process emotions success- fully could explain the emergence of conditions such as PND depression or post-birth traumatic stress. Little direct information exists about how interaction with care givers might support emotional processing

per se

, but evidence does suggest that how the midwife deals with emotion can have a significant impact on women. This can be in terms of women’s decision- making (Edwards 2009) and level of anxiety at the time (Byrt et al. 2008; Hunter et al. 2008), but it is also suggested that the midwife–woman relationship is an important aspect of satisfaction. This is linked to the level at which women feel involved in and have some control over, the process of their care (Slade et al. 1993; Tinkler and Quinney 2001). Evidence suggests that a woman’s feelings of being ‘in control’ are impacted on by the positive attitudes of the midwives caring for them, information giving during pregnancy and labour and being able to make and be included in decision-making during labour (Gibbins and Thomson 2001; see Chapter 3: ‘Antenatal midwifery care’, where decision-making is examined in greater depth). This could be defined as supportive care, which has been identified both qualitatively and quantitatively as an important variable with regard to more positive experiences for women (Waldenström et al. 2004; Kitzinger 2006; Kirkham 2010). Conversely, reduced levels of control and satisfaction havebeen linked to more enduring negative psychological consequences for women, such as PTSD and depression (Czarnocka and Slade 2000; Nilsson and Lundgren 2009) and poorer adjustment to motherhood (Dimatteo and Khan 1997).

The psychological impact on women of the way that midwives interact with them seems clear, but equally important is how midwives manage their own emotions.

The psychological impact on women of the way that midwives interact with them seems clear, but equally important is how midwives manage their own emotions.For midwives

75Emotional work is a feature of all human relationships and is about dealing with our own and other people’s emotions. Interactions between midwives and women as already suggested are social encounters, but ones that often happen in non-ordinary circumstances and involve inti- mate procedures and personal information. Midwives need to manage their feelings so that they are appropriate to the situation they are in (Deery and Hunter 2010); however this can be at cost to the worker who must maintain a professional demeanour (Edwards 2009). The require- ment for midwives to give the right emotional response to the clinical situations that emerge has been reported in several studies as challenging and stressful (Deery and Kirkham 2006; 2007; Earle et al. 2007). Billie Hunter (2006) writes about four key situations which midwives encounter; these include balanced exchanges, rejected exchanges, reversed exchanges and unsustainable exchanges. The latter three exchanges require high levels of ‘emotion work’ by the midwife, whilst balanced exchanges, where there is ‘give and take’ on both sides, are more emotionally rewarding for the midwife. This highlights the clear significance of positive relation- ships for midwives as well as women, which can happen even in the face of adverse outcomes where a supportive relationship has enabled the situation to be as good as possible in the cir- cumstances (Deery and Hunter 2010).

. . . When a meaningful relationship is created, emotion work is not experienced as hard work but is something akin to a gift . . .

(Bolton in Deery and Hunter 2010)Often, however, midwives employ strategies to remain detached. Ruth Deery (Deery and Hunter 2010) describes:

Technical detachment:

The fragmentation of a woman’s care into manageable tasks in order to maximise the midwife’s control of clinical decision-making.

Emotional detachment:

Aimed to protect against over-involvement with women, often engaged in times of high anxiety, which might have short-term benefits for the midwife.Whilst these types of strategies are most often engaged to enable midwives to cope, they inevitably create boundaries and distance from women. Strategies also include stereotyping women as a way of discounting needs that cannot be met (Deery and Kirkham 2007). The problem with such approaches is that they lead to a task-oriented, de-personalised approach, low morale, stress and burn-out (Hunter 2004; Deery and Kirkham 2007). Those relationships that are emotionally positive, underpinned by mutuality, trust and genuineness contribute not only to job satisfaction, but also the midwives sense of self, as a person not a role (McCourt and Stevens 2009). Where midwives keep their ‘

Other books

Jaid's Two Sexy Santas by Berengaria Brown

It Had Been Years by Malflic, Michael

Code Blue by Richard L. Mabry

Everyone Dies by Michael McGarrity

Naufragios by Albar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca

Berried Alive (Manor House Mystery) by Kate Kingsbury

Pisces: From Behind That Locked Door by Pepper Espinoza

A Regency Invitation to the House Party of the Season by Nicola Cornick, Joanna Maitland, Elizabeth Rolls

Blown Away by Shane Gericke

Wrapped in the Flag by Claire Conner