Funeral Music (15 page)

‘Anyway, Sawyer was going through the archive gradually, getting to know what there was. Rationalising, he called it. He was very keen on order, according to Mrs Trowels. She approved of that.’

‘So did he make much progress that afternoon, “rationalising”?’

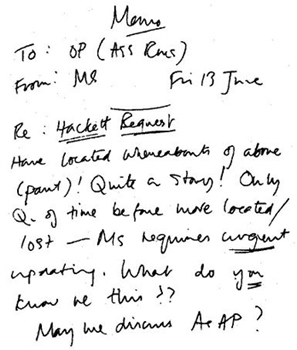

‘It seems he did. He sent a handwritten memo to Olivia Passmore’s office at the costume museum from the art gallery, via the internal mail system. He was very methodical; he photocopied it and had the copy sent back to Mrs Trowels at the Circus for filing. I made a copy of the copy for you – here.’

He stood up, reached into his back pocket and pushed a piece of paper across the table to Sara. ‘Brisk,’ she said. ‘Shocking writing. Not even clear what he means.

Wrote it in a hurry, I’d say. What

does

it mean?’

‘Mrs Trowels explained it to me. In the archive there’s part of a catalogue of a collection called the Hackett Bequest. Sewing boxes and what-not. Needlework tools, silver scissors, thimbles and such. Only the bit of catalogue survives. The actual collection was destroyed in 1941 when a bomb hit the back of the museum offices in the Circus. Everything in the basement was destroyed, either by the bomb or by water, including the Hackett Bequest. The original handwritten catalogue survived. I think it was kept somewhere else. Obviously Matthew Sawyer had tracked it down in the archive, and found it in a bad way. He wanted to get some conservation work done on it, that’s all.’

‘And Olivia saw the memo on the Friday afternoon?’

‘Yes. She confirms the Hackett Bequest details – that was common knowledge. It was nothing new to her, this story about the lost bequest, but she wasn’t sure if Sawyer had heard it. Presumably he had, or had got part of it. He was obviously quite excited about coming across the catalogue fragment. And the catalogue did need rebinding, she said. It would have been done within the next six months anyway; they have a system for checking the state of things in the archives. The memo seems to have been pretty unimportant, to her at any rate. She didn’t even keep the original. Anyway, after he’d finished in the archives and sent the memo, he went over to the Roman Baths and Pump Room – he often did that, just looked in on staff, “walking the job”, he called it – and then went back to the Circus.’

‘And I bet the sainted Mrs Trowels made him his tea?’

‘She did. He got back at about half past four. He asked Mrs Trowels to ring to see if Miss Passmore would be free at quarter to six for a short discussion, and she said she would. And he was at his desk at quarter past five when Mrs Trowels went home. She popped in to take away his cup and say good night. She says his DJ was hanging on the back of the door. He must have changed soon after and gone over to the Assembly Rooms for his meeting with Olivia Passmore. She says he was there just after quarter to, and the kiosk staff saw him come in too.’

‘And I saw him a little while after that. He came out of an office – Olivia’s, I suppose – and talked to some people in the vestibule. A man and a woman. I met her later on; the man went off.’

‘Yes, I’m sure we’ve got the names of everyone he spoke to from then on, until the last of the staff left the Pump Room at twenty to midnight. He saw them off at the Stall Street door. In all that time he was never alone, except for some time back at his office, and walking between there and the Pump Room.’

‘When was that?’

‘Can’t be precise to the minute about that. But he left the Assembly Rooms about half an hour after he’d made his welcome speech. He was in the Tea Room all that time, talking to delegates.

We know he chatted to a group of three or four of them and said something about going back to his office, it was a great time to catch up because it was completely empty then.’

‘Do you think it could have been someone at the convention, you know, prepared to kill him for what he said about natural healing? Only if it was, following him back to the office and doing it there would have been simpler, wouldn’t it?’

‘Yes, if the murderer knew that that was where he was going. But it’s stretching it a bit far, isn’t it?’

‘Probably, but some of them take it very seriously. And there

are

people who are capable of anything if they’re sufficiently worked up.’

‘Yes, but don’t forget the weapon. A kitchen knife. You wouldn’t keep one on you, just in case you felt the need to kill someone.’

‘Have you found out where the knife came from?’

‘We’ve found out all we can. German-made, sold widely, department stores, specialist kitchen shops, singly and in sets. Yes, they’re sold here. And in Bristol, of course. The kitchen shop in Quiet Street does its sales totals by the week and we know that four knives of that type and make were sold in the week before the murder, and three in the week following. The murderer may have bought a knife in advance, you see, knowing what he, or she, was going to do with it, or, more likely I think, gone out afterwards and bought a replacement for the knife they used, so that it wouldn’t be missed. Most were card transactions and we’ve checked them all out. As you’d expect, nothing of interest to us, because the murderer would almost certainly use cash. A total of four were paid for by cash, two in each of the two weeks, but there’s no way of following them up. The staff don’t remember who bought the knives. It’s a busy shop. None of the Coldstreams staff, either at the Pump Room or the Assembly Rooms, has replaced a knife or missed one. Not one of them specifically recognises the actual knife that was used, it’s too familiar a type. No help there. So, we know that Matthew Sawyer rang his wife from the office at seven fifteen, told her where he was and said he was staying for an hour or so. She says that he always used to say “an hour or so” and it could mean anything from an hour to nearer two. But Sawyer was at the Pump Room at nine, after dinner had started.’

‘Doesn’t get us any further, does it? And it’s exactly two weeks now.’

It didn’t. But when they went back up the path in the fading light and played the middle movement of the second Haydn cello concerto in the hut under the slanting shadows cast by the storm lanterns, Andrew felt inexplicably optimistic, delighting in the full-throated, deep singing of the Peresson cello. It was almost dark when they dowsed the lanterns, closed the hut and carried the instruments back down to the house. Sara followed him out to his bike and stood brushing the flowering tips of the huge rosemary bushes through her hand as he unpadlocked it from the railings by the gate.

‘Mind you lock up, now,’ he told her almost tenderly, reluctant to leave her standing there alone. He was much later getting home than he had said he would be and he told Valerie that he had had to nip back into the office after his lesson. It was the first time he had lied to his wife without actually being unfaithful.

CHAPTER 15

BY THE FLACCID whump of the door closing and the sigh of the bag dropping on the hall floor, Cecily got an inkling that Sue was depressed. Or perhaps, being depressed herself, she was simply more attuned to other people’s misery.

‘In here,’ she called, and went to put on the kettle. Sue dripped into sight and slumped in the doorway of the kitchen, seeping deprivation. Cecily took one look at her, put back the coffee jar and took down the instant chocolate, leaving the painted tin of Charbonnel et Walker, Derek’s ‘proper cocoa’, which she happened not to like, untouched. She made two large mugs of chocolate with extra powder and, sighing, stirred some gold top milk and two sugar lumps into each one.

‘Bring those,’ she said, pointing with her nose at a packet of chocolate digestives, and carried their mugs through into the sitting room. Sue obeyed and followed, her feet performing a little collapse with every step, and fell into an armchair. They sipped in tandem, each staring into the cold fireplace.

‘Oh,

God

,’ whispered Sue, rubbing her eyes so hard she seemed to be mashing them. It was the first words she had spoken since she arrived. ‘I shouldn’t be here. I wish I wasn’t.’

‘Oh, now, Sue, don’t,’ Cecily protested. ‘Don’t say an awful thing like that. You’re young and beautiful. Have a biscuit. What you’re feeling now will pass, you know. It

will

,’ she said, silently hoping that what she was feeling would too, despite being no longer young nor ever exactly beautiful herself. Attractive, maybe. Once. Sue stared at her.

‘I meant here.

Here

. In the house. It’s the weekend. You know – your boyfriend, the arrangement?’

‘Oh, I see. Oh, well, that’s a relief. I don’t have to lock up the aspirin then.’ She tried a bright smile, then sipped miserably at her chocolate. She took another biscuit.

‘It doesn’t matter, not this weekend. He’s with his

wife

.’ She said ‘wife’ in a voice like a swishing blade.

‘Oh,

God

,’ said Sue. ‘And Paul’s in Bristol, with God knows who.’

It was twenty past three on Saturday afternoon. It is a depressing time in itself, twenty past three. Twenty past three is about the time, Cecily reflected, when it dawns on you that all those useful things that you vowed to achieve when you woke up determined to be brave about being dumped for the weekend will not be achieved, because you have dithered sluttishly through the day. The oven is still black and sticky, the kettle is still encrusted with limescale, the bed lies unmade, you still have not flossed, and your eyebrows, because you have still not had a proper look for the tweezers, still look like two brown caterpillars about to mate on your forehead. Yes, it is around twenty past three that you find yourself staring hard into the truth that you are such a slattern it can hardly come as a surprise that you have been dumped in favour of a bright, groomed, smiling, competent

wife

.

She had got up with brisk discipline. Today would be like a day at a health farm, only at home, and hers would have the added feature of a few heroic domestic victories as well, like the oven. And she would bravely remove all the little dead lobelias and geraniums that she had planted up lovingly in her urn a few weeks ago and which had sadly and inexplicably died. She must have overwatered them, but just in case there was something wrong with the compost, she would replace it and start all over again. But the main thing for today, this book said, was to learn to treat herself as if she were a celebrity. Celebrate the Celebrity Within You. That way, you would enhance your self-esteem and soon other people would start to notice and treat you better too. Celebrate your inner self, and get acquainted with the celebrity within. She knew how to do it, she had read the whole book twice since she had bought it at the Healing Arts thing, along with all the organic vegetable and fruit-based skin, hair, nail and body preparations she needed to lard herself up for a forty-eight-hour orgy of relaxation, toning, moisturisation, energising and balancing. It said to start by wearing loose comfortable clothing. She had got dressed in one of Derek’s huge T-shirts which had had the effect at first of making her feel small inside it, slapped some cleansing cream on her face and gone down to fix a healthy breakfast. She had whizzed up a chopped apple, a banana, an orange and a tin of peaches in the Magimix and produced a pale orange porridge that had tasted a good deal better than it looked, when it was helped down with a dollop of yoghurt and a couple of spoonfuls of honey.

Feeling too full to tackle the oven, she had plodded up to the bathroom to remove the face cream and embark on the day’s beauty therapies, starting with her hair. Despite having to swathe her head in an old towel which now had more orange and brown blobs on it than a leopard, and wear horrible little plastic gloves like the ones doctors put on when they are about to shove their fingers where they oughtn’t to go, she managed to uphold her inner celebrity pretty well. She maintained it even as she slopped the glossy gravy of the organic dye lotion into her hair and carefully combed it through, hoping, as she had hoped with every hair colour she had used for the past thirty years, that this one would be The One. The one that would make men under thirty turn and stare after her, the one that would make Derek startle and say,

Why, you’re beautiful

, the one that would give her hair the colour, shine, health and bounce that it was

meant

to have. The hair that would have got her a degree instead of a secretarial diploma, the hair that would not have let her be dumped by her boy husband after the second miscarriage in 1970, the hair that would have seen to it that the body it was attached to was an eight-stone, five-foot-nine model, instead of the rounder, shorter specimen that she actually inhabited. Cecily’s last skirmish with a hair colourant (Honey Ash Blonde) had left her hair looking whitishly rubbed out, curiously like the surface of limed kitchen cupboards. This one, she was confident, would restore some depth, a bit of soul.

Not daring to risk dripping through the house, she sat upright on the bathroom stool for the required twenty minutes, cursing that she had forgotten to bring up a

Cosmo

to read. Then she spent another fifteen minutes with her head upside down in the basin, groping blindly for the taps in her efforts to sluice the stuff off. Eventually, after filling and emptying the basin seven times, she decided that the straw-coloured water that ran off her head was as clear as it was going to get. In her bedroom with the hairdryer, Cecily pictured herself emerging with the sort of gleaming curtain of hair that goes with those laughably perfect teeth in the shampoo adverts, the kind that make you worry that hairdressers are in league with dentists and working together in secret to create a master race. But the finished effect was as if the limed kitchen cupboards had been vandalised with Marmite.

The book did not say anything about dragging alarmingly generous tufts of your own hair from the plughole or scrubbing the brown tidemark off the basin but, when these little details had been seen to, Cecily reckoned she was due for a sit-down and some deep breathing. Quality time, to think positively about some aspect of your life that you want to change, the book said. Like, maybe, not getting so worked up about hair colourants, or clearing fat greying headmasters out of your life, she wondered. But it had been impossible not to let her mind dwell on the trim figure, the naturally dark, burnished head and the solid career of smug, married Mrs Payne. She had pulled out the only photograph she had of Derek, the one of him in a suit holding a fountain pen that he’d had done for the school brochure and moped over it. There was none of him and her together.

From that point she had not really risen from the sofa again, except to fix lunch which was meant to be a light salad (no mayonnaise), wholemeal toast and a soft-boiled free-range egg. She fried it instead and had it with oven chips. She spilt ketchup down the T-shirt, which was now making her feel huge. And shortly after that Sue had arrived, and Cecily was finding it oddly comforting to be in the company of a fellow dumpee. The photograph of Derek lay curling gently on the table beside the biscuits, old copies of

Cosmo

and the stupid book.

Sue was saying, ‘Paul went off to Bristol again. He said it was to do with this antiques thing that he’s got going with this bloke in Paris.

We had a row, so I went round to stay at my Aunt Livy’s. She was out and there’s these workmen all over the place, installing this thing. And the day nurse is on at me every five minutes: can’t I make them their tea and watch them with the paintwork, my grandad’s not very well and she’s got his diarrhoea to see to. I couldn’t stand it. I wanted some peace and quiet. It got on my nerves, so I came here.’

‘Was it a bad one – the row, I mean?’ Cecily asked gently.

Sue gave another long sigh. ‘He was in London the other day, wouldn’t say what for. I was hoping it was to do with, you know, us. Him and me: a job, or a course, or

something

, so that we could be together properly.’

She looked into her mug and swirled the dregs around. ‘It’s my fault. I was expecting too much. Anyway, he didn’t say a word when he came back. That was on Thursday. Then today he hands me a little package. It’s in a Harrods bag and I can feel it’s a box. I forgot to give you this, he said. It’s only a small thing.

Well, I was over the

moon

. I thought, Oh, how

sweet

, he’s waited till the weekend.’

‘What

was

it?’ Cecily asked breathlessly.

Sue continued to stare into her mug. ‘I suppose it’s quite funny in a way. I was that thrilled, he couldn’t understand why. I thought it was a ring.’ Her eyes filled with tears.‘And it was a pair of Donna Karan trainer laces.’ She paused. ‘They’re nice. As laces. But that’s not the point, is it? So I just burst into tears and he got mad with me. And he just refuses to discuss it: won’t say we won’t ever get married, won’t say we will. And then he says don’t forget he’s going to Bristol today and won’t be back till tomorrow. He said he’d told me. He hadn’t, though.’

There was silence. They felt the crushing weight of twenty-three minutes past three. Sue reached for a biscuit. Cecily leaned forward and pushed the photograph of Derek across the table. Then she leaned over and picked a pine cone from the top of the basket that filled the fireplace and began thoughtfully pulling it to pieces.

‘That’s him, that’s Derek. He’s having a party tonight. Or his wife is. He’s doing the cooking,’ she said flatly.

Sue, with her mouth full, tried to look sympathetic.

‘You know she’s been running these courses? No, I never really told you, did I? Well, it won’t do any harm. He’s my boss. She’s an education adviser, and she’s been running these courses for teachers. That’s why Derek and I have managed to have so much time together.’

Sue nodded.

Cecily went on, ‘They’re finished now except for the assessment, so she’s giving them all a nice little farewell supper and Derek’s doing the food. She expects him to.’

‘Well, he’s got to then, hasn’t he? He hasn’t got any choice. He’d probably much rather be with you.’

‘I don’t know. He likes all that mein host bollocks, and I think half the time he pretends she makes him do things. And the weekend before last wasn’t too good.

We had a row on Friday night at the Assembly Rooms and he stormed off. He was meant to be picking me up later but he didn’t. I had to get a taxi back and the house was empty. I was furious. I was soaked through so I just had a bath and went to bed. I left him a blanket on the stairs. God

knows

where he went off to – he never really said.

We made it up in the morning. We went shopping. Only for him, as usual. But everything was okay after that, or I thought it was.’

‘Well then,’ Sue said, without confidence.

‘You know, I think I’m just fed up with it all. I’m still angry with him for wasting our time like that, when we don’t have much. He’s just fooling around. He used to say he hated weekends with his wife, but he’s obviously looking forward to this one. The bastard is doing a fork supper for forty fat fucking infants teachers rather than spending the night with me, and he’s

looking forward

to it.’

She tore at the remains of the pine cone. ‘Picture it, them all simpering into their Frascati and congratulating her because her husband’s in a pinny:

“Oh, aren’t you lucky, I don’t

think mine even knows where the kitchen is!

” Ugh.’

She seized another pine cone and ripped it in half. ‘Do you know, last week he actually consulted me about the menu? Did I think they’d want bread as well if there was a pasta salad.’

‘Incredible,’ Sue said, shaking her head. She reached for her own pine cone and began systematically taking it apart.

‘Yeah. Then I volunteered to do a pudding, and just for a second, not only did he think I was serious, he nearly accepted. “

Oh, would you really have time? Perhaps a trifle?

” he says. And I said sure, it wouldn’t take a minute to grind some glass.’

Sue snorted bitterly.

Cecily went on, ‘And then he went huffy with me for the rest of week.

He

went huffy. So yesterday, last thing, I told him he could make his own fucking trifle,’ adding in a small voice, ‘in front of the chairman of the governors.’

In the silence that followed, she looked despondently at the little pile of brown dusty shreds that had accumulated in her lap.

‘I don’t want a lot, you know, nothing that other people don’t have. I’d just like’ – Cecily turned two huge, tearfilled eyes to Sue – ‘I’d just like to be

secure

. He said he’d look after me. I thought that meant he’d be leaving her. He

knew

I thought that. Just a bit of security – it’d be so nice. Not to have to worry. That’s not greedy, is it?’

She waved unhappily in the direction of the urn outside, in front of the sitting room window. ‘Things like that,’ she said, sniffing, ‘little things. Going to the garden centre now and then. Being able to spend a bit, without panicking afterwards. Doing things together. It’s not a lot, is it?’ She sniffed angrily. ‘S’not going to happen, though. And after all I’ve done for him! When I think of how I’ve helped him, how he said we’d be together. God, the things I’ve done for him!’