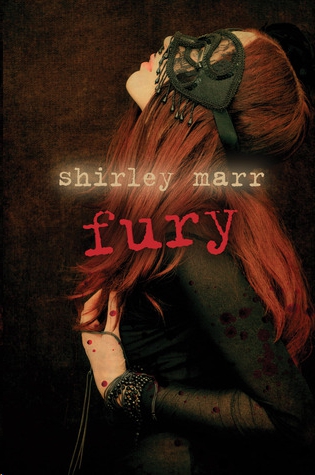

Fury

Authors: Shirley Marr

Tags: #Teen & Young Adult, #Literature & Fiction, #Fantasy, #Young Adult, #Mystery, #Suspense, #Thriller, #Crime, #Contemporary

My name is Eliza Boans and I am a murderer.

I

know.

It’s pretty shocking, huh?

To think I actually had a better surname before my parents divorced and my mother went back to her maiden name, taking me kicking and screaming with her. See, the judge gave Dad the Jag and gave Mum, well,

me.

She spewed big time over that. But seriously, unlike what that do-gooder Chaplain here thinks, I didn’t just wake up one morning and say to myself, “what a lovely day, I think I might go out and kill someone.”

I’m the last person that anyone would have suspected. I’m just Lizzie, typical teenager. I’m all about angst, attitude, designer labels and cupcakes. I want to grow up and do something cool with my life, such as build an orphanage in a third world country like all those saintly Hollywood celebrities. That or, like, cause a scandal and become mega-famous. Everyone knows that’s how you get noticed these days. I live in the suburbs, go to high school, and my mum has all these unrealistic expectations of how well I’m going to do in Year Twelve blah, blah, blah. The only difference between you and me is that I live in East Rivermoor.

A great wall runs all the way around our suburb. Access is through a double gate that has our own special crest on it. This is not just any neighbourhood; check your reality before you enter.

There is everything that you could possibly want here. The best shopping and heaps of trendy cafés, bars and restaurants that always get drool-worthy reviews in the magazines. A huge park in the middle with acres of rolled-on green lawn and a lake so large it has its own suspension bridge. You can keep your fancy yachts here; the water eventually takes you out into the ocean. Well-buffed guys practise rowing on weekends.

It’s not a right to live here; it’s a privilege. A privilege of being rich. There’s no need to go outside these walls, if you don’t want to.

I go to Priory Grammar of East Rivermoor, which everyone refers to by the one word:

Priory.

Makes it sound like a white

monastery or a glass hospital. It’s private, of course; as if it would be a public school. You need to, like, have money to live in East Rivermoor in the first place. Sure, we have scholarships for smart students from the povo suburbs, so you can get in if you’re special and your parents aren’t. But I don’t know anyone here who has a parent below a doctor, lawyer, CEO or self-made entrepreneur.

At Priory, no expense has been spared for the offspring of the elite. No concrete landscaping or cyclone fencing here, unlike other schools I’ve only heard rumours of. Priory’s been the top Tertiary Entrance Exam ranked school five years in a row. It’s all beautiful and perfect. Even the girl’s toilets smell like vanilla cake.

Don’t get jealous just yet. Let me tell you my story first. It’s

really

awful. Something worse than making a fool of yourself in front of the cute boy you’ve been eyeing all semester; much worse than showing up to the end-of-school ball in the same dress as the best looking chick in your grade. It’s about a crime me and my best friends committed. No one thought that what I did could happen. Not in a safe place like East Rivermoor Not in a snobby, insufferable place like this.

I think you can tell by now that this is not going to be a happy story. If it were just some teenager’s account of the last sunshine-filled days of high school, topped with a graduation and coming-of-age lesson at the end, then I wouldn’t bother. You can go and read, like,

Snatcher in the Rye

or whatever, with the losers not doing English Lit.

The truth is we—me, Marianne, Lexi and Ella—never even made it to our graduation.

I heard that Isabella Hervey spiked the fruit punch and that Professor Adler snogged Miss Bailoutte behind the DJ booth. Like,

eww

old people. There was also reportedly a bitch fight on the dance floor involving the school football captain Richard Edwards, two admirers and a misdirected text message. What a shame we never got to see any of that for ourselves. Nobody signed our yearbooks. If we asked now, no one would want to.

The graduation song turned out to be

Extraordinary

by Mandy Moore. Fireworks exploded over everyone’s heads as they made their way outside the school auditorium. It was a really touching moment, apparently. I guess the song wasn’t intended for us. It doesn’t matter: that song is crap.

Instead, the four of us spent what was supposed to be our graduation night locked in separate rooms at the police station in the city. We weren’t allowed to see each other. They told us that we had done enough damage already. Maybe they thought that if they put us together we might kill each other. They already believe that we’re capable of murdering somebody.

Ella’s mother was the first to come, armed with huge bagfuls of food. She cried when that detective or whatever he is—Dr Fadden—told her she couldn’t give them to her daughter. He told her that Ella deserved punishment. Mrs Dashwood sobbed and said that Ella was just a little girl.

Dr Fadden folded his arms. It said, silently, that he thought Ella was old enough.

Let’s get one thing straight. I don’t expect you to feel sorry for me. Hell, I don’t think Mum does. That’s why I’m not going to give her the chance to tell me how much I’ve failed her. I refuse to see her, or that woman-lawyer she’s hired for me who specialises in “troubled” teenage girls. The only commitment I’ve seen them both demonstrate is trying to outdo each other in the short skirt department.

As for my dad, well, I don’t have what you call an

active dad.

Not anymore. He walked out on us a long time ago and he never looked back. In fact, he took off so fast he’s not even in the same country anymore.

Boohoo

you’re probably thinking.

Poor little rich East Rivermoor girl.

Yeah, I should probably go and cry into my new Fendi handbag that Mum bought me. That might make me feel better.

They found the body Tuesday morning. A group of kids who walk to school along that way discovered it. I never meant for anything like that to happen. I mean, those kids were only in Year Eight. I’m really sorry that they’ll probably have to be in therapy for the rest of their lives, but their parents should know better than to let them walk along the border of East Rivermoor to get to school. Beyond the border is the rest of the imperfect, dangerous world.

If I had known better I would have kicked that body and rolled it down that ditch. Then maybe it would have stayed there undisturbed until it rotted away to bone, and then from

bone to dust. Right next to the billboard advertising what a wonderful place East Rivermoor is to live.

I’m not sorry I killed the person that body used to be.

They took Ella first, on the afternoon of that same Tuesday. She was at home freaking out. I guess she had reason to, considering how close the body was to her house. Then they came to take me, Lexi and Marianne.

We were all at my place studying for the English Lit final. They knew we were there; it was quite obvious who told them,

cough-that-snivelling-traitor-Ella-cough.

When I opened the door, the dried bloodstain I was wearing over my heart like a badge of honour told them,

these are the ones who did it.

When they got the cuffs out, it said,

these are the ones who deserve it.

Mum wasn’t there when they came to knock on the door. In fact, she hadn’t been home for two weeks. I had no idea where she had gone or who she was with. Her very important work takes her places and she often has to jet off just like that. Well, now that she has finally rushed back, it’s too late. I think that’s fair enough for me to say. She was supposed to be there for me from the start. I know she’ll be devastated that I’m going to miss my exams. Mum wanted to see me go to a good university, i.e., the one that she went to. I guess I’ll just have to take the exams next year. That’s if I’m allowed to. Do they let you sit the TEE if you’re in jail?

Dr Fadden has made it clear that we will be going to a proper jail. We won’t be going to some “cushy” juvey

detention centre or some “rejuvenation” hospital by trying to pull an insanity plea. He says the law is going to come down hard, like, “you don’t even know

how hard”.

He says the law doesn’t care if we are children; we have committed a very adult act and will thus be treated as adults.

I know the doctor thinks I am a spoilt brat. He doesn’t need to tell me that; I know I am. As for his thinking that I need to be taught a lesson—I didn’t think it was a crime to live in an expensive house, own sixty-five-and-counting pairs of shoes, have my own credit card and be promised a sports car when I get my licence. I know what lesson he really thinks I need to learn. I know guys like him: the ones that live on the other side of the wall. He doesn’t know anything about me.

So let me introduce Dr Fadden. I thought I’d seen the end of him, after he spent last night grilling me. But this morning, to my horror, I find that he’s the caseworker assigned to me. He’s kind of hardened and mean, even though he looks young and reckons he is not technically a cop. He says he’s an anthropologist. Maybe he thinks he can study the truth out of me. Maybe he’s hoping that if he cracks this case and put us all away for life, he might get promoted to some cushy high-profile cop job. I am not sure how much money anthropologists make these days. Probably not a lot.

Since this

doctor

already knows I am guilty, his job is to find out to what extent. I take it the police have found more than one set of prints on the knife. So I’m going to try my hardest to hate him. I know that he’s going to try and turn

me against my friends so we get hysterical and point fingers, but I’m not interested in playing his games. I know better than that. After all, they say the apple doesn’t drop far from the tree. And I just happen to be the daughter of the highest profile female lawyer in the state. The one they call

Bombshell

Barrister Boans.

“Let’s go over this again,” says Dr Fadden. “Is there anything else you want to tell me, Eliza?”

I put my forehead down on the table.

“This is not helping,” says Dr Fadden, unhelpfully.

We are seated in some really disgusting, dingy room. It has a metal table and chairs so old and ugly, I reckon even the residents of Middlemore would be too embarrassed to put them out as kerb collect. There’s one of those fluoro-tube lights on the ceiling: the type that blink and make a humming noise. I have never seen a single building in East Rivermoor with one of those. I have to say that it does not impress me.

“Why are you interviewing me?” I ask. “Aren’t you supposed to be an anthropologist? Shouldn’t you be looking at the body instead of looking at me?”

“Lack of funding in the police department,” replies Dr Fadden without skipping a beat. “Plus I’ve already looked at the body.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Whoever was responsible for the stabbing plunged the

knife so hard into the chest, it pierced the rib cage. We found miniscule fragments of bone on the blade.”

“Cheery,” I reply.

“I work with live humans as well, if that helps answer your question.”

I try to think of some derogatory names for him, but not a lot of words rhyme with Fadden and I give up at “Dr Fathead”. But I know he’s not just some dopey, doughnut-eating cop I can completely dismiss. I can see it in his eyes. They appear to be connected to a brain. Maybe he is mean to me because he thinks I am cruel.

Dr Fadden has what my mum would call a good Mediterranean complexion. His eyes turn slightly downwards at the corners, which give him a permanently sad look. I watch him from where my head still is, on the table with my cheek pressed against the cold metal. Maybe I will regret trying to play up when the side of my face breaks out in zits. I want to hate him. He’s making it hard by being good-looking.

“Can I have a coffee?”

From my position I can see Dr Fadden’s sideways face raise its eyebrows.

“I’m sixteen, not ten you know.”

“I know,” he replies. “I’ve read the police report. In fact, I’ve read your entire file and I probably know your life better than you do.”

I pull my head back up.

“I’ve been drinking coffee since I was, like, thirteen,”

I say and try to sound mature. “And I’ve been sitting in cafés drinking frappucinos since I was maybe ten. It’s—y’know—normal.”

I can see him looking at the dirty school uniform I still have on, and my messed-up hair, and the blood as the words “We grow up pretty fast these days, trust me,” come tumbling carelessly out of my mouth. And I know he is wondering.

“Okay.” He shrugs and stands up.

“No!”

It comes out as a shout.

“I mean—

please,”

I say and adjust my voice, “can I go with you and make it myself? I’ve been sitting here for hours doing

nothing.

I might get, like, mental damage. Pretty please?”

“May I remind you that this is not a five-star resort?” Dr Fadden says in his no-nonsense voice. “You have committed a very serious crime. I want you to take all of this seriously. For your own sake.”

He doesn’t have to tell me that. I know that this is

definitely

no five-star resort.

“I am,” I reply and I do that thing where I make my eyes go real big. Perhaps I should also quiver my lip for effect.

The doctor sighs.

“Quickly then. And if anyone sees you, you’re responsible for making up the excuse. Come on.”

I don’t move at first. I sit exactly where I am with my hands clenched between my knees.

“Out,” he says firmly like he’s talking to a dog, or like he’s

a man on a commercial ordering a beetroot stain off the collar of a white shirt.

I move.

Yes,

I think silently, and in my head I do an arm-pump thing like a dumb-ass cheerleader. I know he’s just trying to score brownie points with me, but I like Dr Fadden a bit better. He is young and impressionable. Maybe if I keep a tight leash on him he won’t get the better of me. I learnt that trick from my mum.

Dr Fadden stands holding the door open. I smile at him as I squeeze eagerly past and hurry down the white hallway.