Gabriel's Horses (11 page)

Authors: Alison Hart

“That's right.” Master crosses his arms. “These past weeks you've proven that you have a strong voice, Gabriel. Your mother and father want you to stay at Woodville. But I believe you have a say.”

My mind whirls.

I'm free. Free to leave Woodville Farm and be what I choose. Free to follow Jackson and be a jockey at Saratoga. Free to follow Pa and be a soldier at Camp Nelson.

I stare at the circle of them: Ma, Pa, Master, and Annabelle. I hear all their voices telling me about freedom. Then Aristo scratches his face on my shoulder as if reminding me that

he

wants a voice, too.

My head stops whirling. “

Mister

Giles,” I say clearly. “Thank you for your offer. For now I'd like to stay at Woodville Farm and jockey your Thoroughbreds.” I stroke Aristo's sweaty neck. “I want to stay and train this colt. I aim to build up 'Risto's spirit again, so one day me and him will win such an important race that

both

our names'll be in the

Lexington Observer

.”

Mister Giles grins. “A fine decision!” he says. Ma and Pa break into smiles, too, and then they're all chattering to each other.

Sore and exhausted, I limp toward the barn with Aristo, who's just as tuckered. Annabelle falls in beside me.

“I'm glad you're staying,” she says shyly. “And I do believe you may be right, Gabriel Alexander. One day, I

will

read your name in the newspaper!”

I glance sideways at her. “That's not the only reason I'm staying, Annabelle. Seems I remember someone told me that freedom ain't just about leaving. It's also about caring. I guess I ain't ready to quit caring 'bout these horses yet.”

Annabelle gives me a little smile, and as I walk Aristo into the dark barn, she steps back into the sunlight.

The barn's cool and quiet. I lead the colt past Sympathy, Daphne, and Arrow. Jase is grooming Savannah, and Tandy's rubbing down Captain. Blind Patterson sticks his nose over the stall door, Tenpenny furiously munches hay, and Romance whickers deep in her throat.

Happiness fills me. I'm

free

. Free to be whatever I want and go wherever I choose. Someday soon I'll ride at a famous racetrack like Saratoga. And one day I'll join Pa and the colored soldiers to fight for freedom for

all

slaves.

But for now, I belong right here in this barn.

With my courageous horses.

G

ABRIEL'S

H

ORSES

K

ENTUCKY

, 1864

I

N THE BEGINNING OF THE

C

IVIL

W

AR

, Kentucky was considered a “border state,” although many Kentuckians owned slaves. During the last two years of the war, Kentucky was under Union control. However, President Lincoln promised Kentucky that he would not free their slaves. This would later change when the Union army became desperate for soldiers.

Toward the end of the war, Union troops took over the town of Lexington, Kentucky. Major buildings became military hospitals, prisons, and barracks. Otherwise, however, life in Kentucky was fairly normal compared to life in most of the Southern states, where fighting was heavy and losses in lives and property were great.

Frances Peter, a young girl living in Lexington during the Civil War, discussed prices in her diary:

AShoes $1.25 to $3.00 a pair

Kid gloves $2.00

A turkey $2.00

One negro man $250.00

FRICAN

A

MERICANS

, 1864

B

ecause Kentucky was loyal to the Union, the Emancipation Proclamation did not free Kentucky slaves in 1863. Life for young slaves like Gabriel, Tandy, Jase, and Annabelle was not easy. They were considered “property,” not people. They had no legal rights. They could be bought and sold at the whim of their owners, or “masters.” They could not go to school because it was against the law to educate a slave. Former slave Patsy Mitchner recalled many years later in an interview: “We was not teached to read and write. You better not be caught with no paper in your hand. If you was you got the cowhide.”

Slaves worked six days a week for no wages. Young children fed the chickens, swept the yards, churned butter, and watched the babies. By thirteen or fourteen they were working as hard as the adults. Silas Jackson, a slave during the Civil War, later wrote that they were “awakened by the blowing of the horn before sunrise . . . and worked all day until sundown.”

Even free African Americans in Kentucky were not totally free. At all times they had to carry “free papers” that identified them by age, name, description, the county where they lived, and details of their emancipation. If a free African American went out without this document, authorities could throw him in jail.

Like Gabriel's father, free black men often saved up their money to buy their wives' freedom. That way, their children would be born free. Freedom was so important that one African American traded the factory he owned for the freedom of his son.

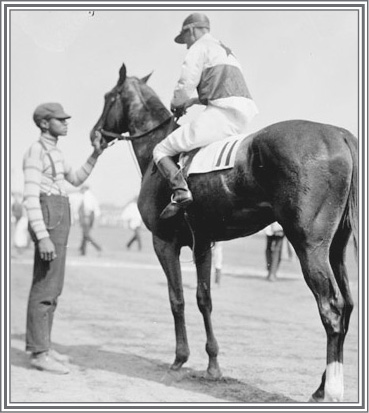

Many historians have called horse racing America's first national sport. Kentucky horse racing dates back to 1789, when the first racecourse was laid out in The Commons, a parklike area in Lexington, Kentucky. During the Civil War, most racing events were halted. But the racetrack at Lexington where Gabriel raced Tenpenny ran continuously, except in the spring of 1862 when Confederates camped on the racetrack.

Races were hard on both horse and rider. A race for a three-year-old might be two or three mile-long “heats.” Handlers washed and cooled off the horses between heats. Still, by the end of the races, the horses were exhausted and often lame. One newspaper account mentioned a horse that had broken down after 9½

miles

of racing. Newspaper accounts also described riders fainting from exhaustion and being beaten and battered by the other jockeys.

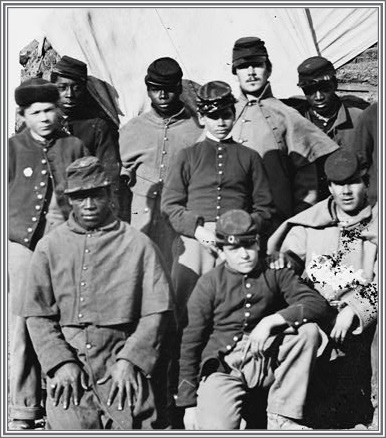

In Kentucky and the South, most of the early trainers and jockeys were slaves like Gabriel, who had been raised with horses. They groomed and exercised horses, cleaned barns and tack, and slept in the stalls. They began to ride in races as early as ten years old.

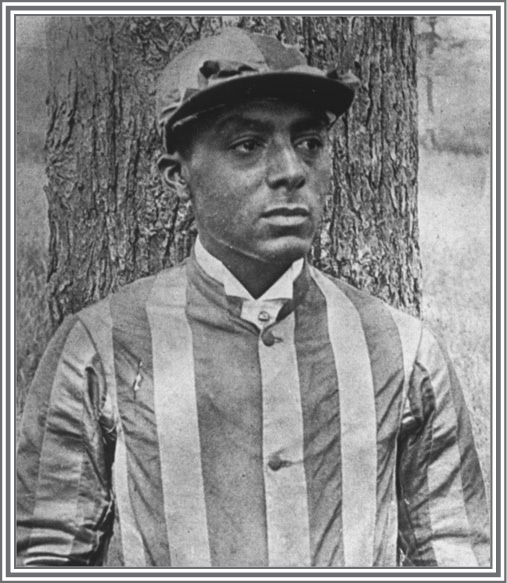

One of the first great jockeys was Abe Hawkins, a freed slave. Some consider him to be the first African American professional athlete. He was well-respected and valued for his riding skills, and a favorite of newspapers. In 1866, the

New York Times

called Hawkins “that consummate artist in the saddle.” His crouched riding style became known as the “American seat” as compared to the upright “English seat.”

In the late 1800s there were many talented and winning African American riders and trainers. Ansel Williamson, a slave, was a successful horse trainer for a variety of masters. Freed after the Civil War, he continued to train horses. He is best known for training Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby in 1875.

African American Isaac Murphy has been called the greatest jockey in American racing history. He was born in 1860 in Kentucky. He became a jockey at the age of fourteen and won 628 races, including the Kentucky Derby three times.

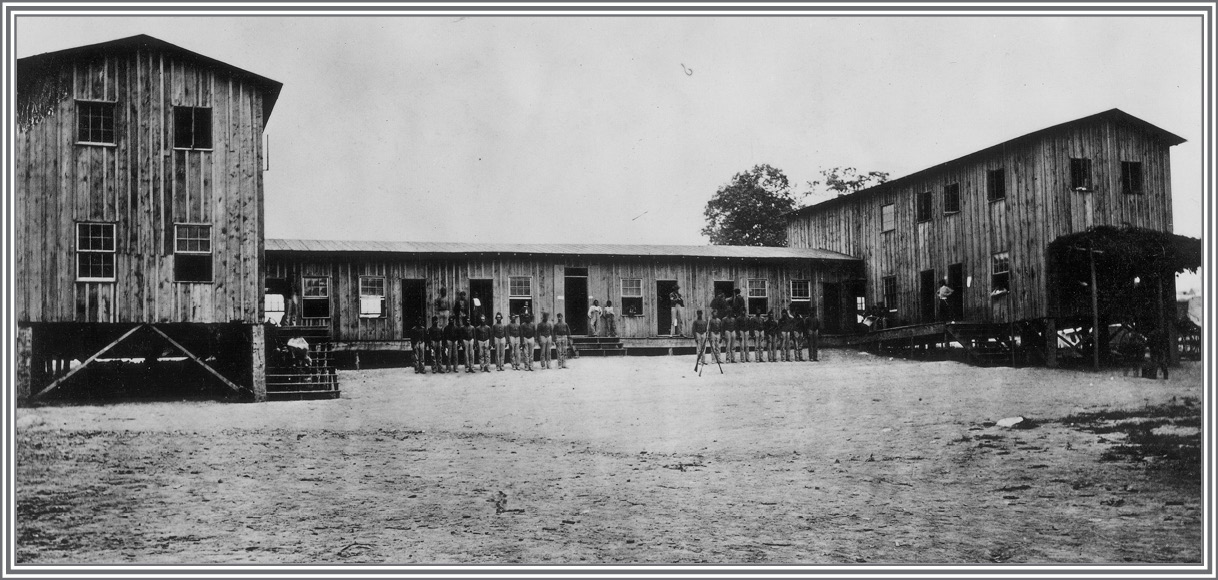

Camp Nelson, where Gabriel's father enlisted, was a Union military camp located south of Lexington. It contained over 300 buildings and covered more than 800 acres. Located within the camp were corrals, a prison, a hospital, a blacksmith shop, a bakery, a laundry, and a Soldiers Home. Set up as a supply depot for Union troops fighting in Tennessee, it also provided and trained horses and mule teams.

Before 1864, the workers who built and ran the camp were generally African Americans who were contrabands (escaped slaves) or those who had been impressed (forced into service) by the army. Recruitment of whites for the Union army began to slow, but the Yankees were still hungry for soldiers. In the Conscriptive Act of February 1864, President Lincoln authorized the use of black troops. Kentucky African Americans, free and slave, poured into Camp Nelson to enlist. In return, the slaves were given their freedom. Their masters were paid $300. Freemen like Gabriel's father were given an enlistment fee.

Camp Nelson soon became the third largest recruiting and training center for black soldiers in the country. From November 1864 to April 1865, nearly 5,400 Kentucky slaves enlisted at the camp. Most of the slaves left the farms without permission from their owners, who often took out their anger on the slave's family. Wives and children were beaten or thrown off farms without clothing and food. Many ran away, following their husbands and fathers to Camp Nelson.

Since the women and children were still slaves, the Union army had no legal right to house them at Camp Nelson. Wives and children were repeatedly driven from the camp. On July 6, 1864, General Speed S. Fry ordered that “all negro women and children & men in camp unfit for service [should] be delivered to their owners.”