Gallipoli (21 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

Many of the men are sure to pen letters of their own, taking the correspondent down a peg or two. One Lance-Corporal writes, âI suppose you have read all that rot by his wowsership C.E.W. Bean ⦠It would be ridiculous to expect an expeditionary force to be all members of the Y.M.C.A. wouldn't it?'

16

Lieutenant Gordon Carter writes to his parents of such reports: âThe peculiar part is that most of their stories have some particle of truth, but that has been so exaggerated as to be unrecognisable.'

17

All that Bean can do is keep his head up and console himself in his diary; âAnyway, my job is to tell the people of Australia the truth.'

18

After all, isn't that what correspondents are meant to do,

come what may?

16 FEBRUARY 1915, 10 DOWNING STREET, THE WAR COUNCIL MEETS

For three weeks now, Sir John Fisher, along with the majority of the Admiralty, has been agitating for a significant ground presence to be assembled to help the fleet to force the Dardanelles.

Although Kitchener and Churchill continue to believe it possible for the fleet to go it alone, Prime Minister Asquith does not. With the war going as badly as it is, the days of Lord Kitchener's say-so being enough to make something happen are gone.

The following key resolutions of this ad hoc meeting will later be regarded by Hankey as the very decisions âfrom which sprang the joint naval and military enterprise against the Gallipoli Peninsula'.

19

â1. The 29th Division, hitherto intended to form part of Sir John French's Army, to be despatched to Lemnos at the earliest possible date. It is hoped that it may be able to sail within ten days.

â2. Arrangements to be made for a force to be despatched from Egypt, if required.

â3. The whole of the above forces, in conjunction with the battalions of Royal Marines already despatched, to be available in case of necessity to support the naval attack on the Dardanelles [and] the Admiralty to build special transports and [small boats] suitable for the conveyance and landing of a force of 50,000 men at any point where they may be required.'

20

The key object remains, however, securing that naval breakthrough, and Churchill, for one, is happy that a bombardment of the outer forts is then and there being planned.

7.20 AM, 19 FEBRUARY 1915, THE DARDANELLES HAVE THEIR OUTER DEFENCES TESTED

Following the attacks of the previous years, it is likely that the British Fleet will try to force the Dardanelles again, and so it is no surprise to the Turks on this misty morning when, just before 10 am,

Cornwallis

emerges out of the gloom, accompanied by

Triumph

and

Suffren

, firing from long range upon the forts on either side of the entrance to the Dardanelles that guard the way to Constantinople. Taking advantage of the fact that their guns can fire further than those in the forts, whose range extends no further than 12,500 yards, the three battleships stay offshore with perfect safety, launching salvo after salvo. All those on shore can do is keep their heads down and hope to survive.

That becomes more problematic when at 2 pm the ships close to 6000 yards and the fire becomes more accurate still, but at nigh on 4.45 pm the real test begins. Vice-Admiral Sir Sackville Carden sends

Vengeance

,

Cornwallis

and

Suffren

in to 3000 yards, to get in close and pour heavy fire on those four forts, while also testing to see just what the Turks are capable of dishing back.

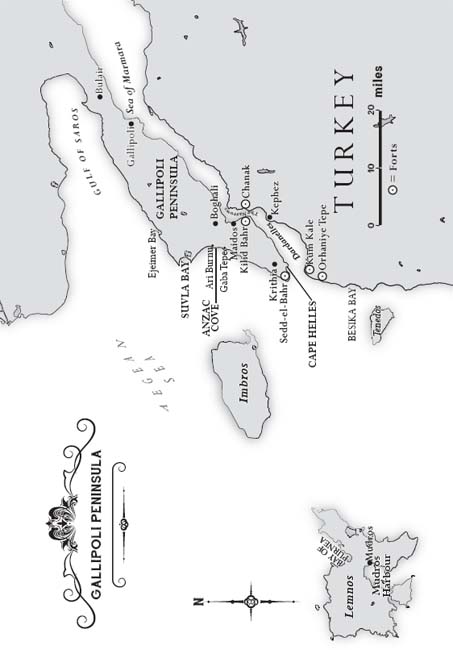

Dardanelles area, by Jane Macaulay

The answer: a fair bit.

That, at least, is the inescapable conclusion of Admiral John de Robeck aboard

Vengeance

after he has ordered the battleship to move even closer to the European shore so as to better inspect the devastating results of their up to 850-pound shells. Suddenly two of the forts, Orhaniye Tepe and Cape Helles, open fire. Clearly, they are

still functioning.

Nevertheless,

Cornwallis

, which has come in to support

Vengeance

, soon achieves the greatest satisfaction of the day when, after several well-aimed salvos hit their mark, the fort at Cape Helles marked as No.1 explodes, in the words of the

Cornwallis

's gunnery officer Lieutenant Harry Minchin, into âa perfect inferno, rocks & smoke, flame, dust & splinters all in the air together'.

21

Beyond that success, though, there is not a lot more to show for the attack as the other forts keep firing, seemingly impervious to the shells that the ships keep pouring onto them.

Although the return fire from the Turks is only spasmodic, it's clear that the guns, unless suffering a direct hit, will remain intact.

At sunset, with the shortage of both light and ammunition, Vice-Admiral Carden withdraws the last of his ships and is firm in his summation: âThe result of the day's action showed apparently that the effect of long range bombardment by direct fire on modern earthwork forts is slight.'

22

For its part, an official communiqué from Constantinople would claim the only damage done was âone soldier ⦠slightly wounded by stone splinters'.

23

23â26 FEBRUARY 1915, LONDON, THE FIRST LORD OF THE ADMIRALTY LORDS IT OVER ALL

True, the whole thing has not gone as planned, but the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, is entirely undeterred. Four days after the attack, and now fully apprised of the whole affair, the man who is the principal architect of the whole scheme is holding court among selected guests after dinner at Admiralty House, and he divulges his growing view that to accomplish the scheme it really will be necessary to land a large body of men on the Peninsula.

Over cigars and port, Churchill pronounces himself âthrilled at the prospect of the military expedition'.

âI think a curse should rest on me because I am so happy,' he exults. âI know this war is smashing and shattering the lives of thousands every moment â and yet â I cannot help it â I enjoy every second I live.'

24

At a meeting of the War Council the next day, Lord Kitchener asks, âAre you contemplating a land attack?'

âI am not,' Churchill replies firmly. âBut it is quite conceivable that the naval attack might be temporarily held up by mines and some local military operation required â¦'

25

In response, the disquieted Lloyd George asks, is it

really

proposed âthat the Army should be used to undertake an operation in which the Navy has failed?'

26

âThat is not the intention,' replies Churchill. âI can only conceive a case using the military where the Navy has almost succeeded, but a military force would just make the difference between failure and success.'

27

Lloyd George is firm: âI do hope that the Army will not be required, or expected to pull the chestnuts out of the fire for the Navy.'

28

Of course not, Winston Churchill assures him.

The War Council also looks at sending a force from Egypt, if required.

âAre the Australians and New Zealanders good enough for an important operation of war?'

29

Prime Minister Asquith asks Field Marshal Lord Kitchener.

âWell,' the good Lord replies, âthey are quite good enough, if a cruise in the Sea of Marmara is all that is contemplated.'

30

On the other hand, he adds a little later, the 8000 mounted Australian troops now gathered in Egypt are good enough to reinforce the Dardanelles, but it will still have to be the British troops who do the hard work.

For all that, Lord Kitchener still can't understand âthe purpose for which so many troops are to be used. What are the troops to do, while waiting?'

31

Lord Kitchener has felt so strongly about it that he reneges on his original decision, peremptorily cancelling the transports to take his 29th Division â perhaps the finest Division in the British Army, just returned from their posting in India and Burma, and other far-flung garrisons â to Lemnos.

It is something that aggrieves Churchill deeply. âOne step more,' he would later recount. âOne effort more, and Constantinople was in our hands, and all the Balkan States committed to irrevocable hostility to the Central Powers.'

32

But a defeat in the Dardanelles? The consequences are unthinkable.

British prestige would be damaged, risking a revolt in India and even Egypt, thus threatening the Suez Canal.

MORNING, 25 FEBRUARY 1915, MELBOURNE, AWAY AT LAST

It has been a long haul, but now the 8th Light Horse Regiment, recruited exclusively in Victoria, too, is on its way. Over the last five months, under the command of the recently promoted Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander White, the men have trained hard and gelled as a fighting unit, and finally received their embarkation orders.

On this day, as the troopship

Star of Victoria

steams out of Port Phillip, the men of the 8th LHR are peering earnestly at Melbourne Town, but none with more intensity than White, still wearing the locket with the picture of his beloved wife, Myrtle, and baby son, Alexander, around his neck. For unlike most of the others looking towards the shore, he actually has a chance of

seeing

his family, and brings his glasses to bear on the suburb of Elsternwick, where his family home lies.

By God, there is Cole Street! There is his neighbour, Armstrong, and his dog! There â his and Myrtle's lovely house, and there ⦠there ⦠there â¦

No, alas, he cannot see Myrtle and wee Alex, try as he might. They must be inside, drat it. Still hopeful, White keeps the binoculars trained until Elsternwick falls irretrievably behind and, more than somewhat deflated, he brings his glasses down.

Already well out on the Indian Ocean on this day, aboard HMAT

Itonus

, Hugo Throssell is impatient to catch up with the rest of the West Australian 10th LHR, the first contingent of which had left 11 days before.

Though hugely disappointed at being left behind, and missing his brother Ric, whom he has rarely been away from his whole life, Throssell at least understands the reason for it. His desperate hope is that he won't miss out on the action.

28 FEBRUARY 1915, IMBROS, LIKE A BIRD ON A WIRE

General Birdwood does not like it, not one bit.

Having been commanded to confer with Vice-Admiral Carden â based aboard

Inflexible

, now anchored in the lee of Greece's island of Imbros, just 14 miles from the mouth of the Dardanelles â Birdwood has journeyed there from Alexandria aboard HMS

Swiftsure

. His first concern is the horrible weather â the freezing cold, the thick mist, the low, heavy clouds â which means the ship can make no more than four knots.

More worrying still is Carden's lack of confidence that the Imperial Fleet will be able to do what it had been charged to do: force the Dardanelles. Most pointedly, it is his insistence that he âmust have troops to land and seize any position from which it might be possible to dislodge the Turks by the guns of the Fleet'.

33

By which he means, of course, Birdwood's troops. But Birdwood is far from convinced that any such move is advisable, and less so when he boards

Irresistible

with his close friend and Carden's second-in-command, Admiral John de Robeck, and journeys as far up the Dardanelles as possible to have a look at the ground they might have to fight on. Of course, they cannot get farther than just beyond Morto Bay, around one mile inside the mouth, before the shells fall so thickly â from guns unseen â that they have to withdraw. Beyond that, the weather continues to be appalling.