Gallipoli (40 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

The order to fire is shouted into the forward torpedo room. The Torpedoman's mate pulls down on a lever that releases an explosion of compressed air into the tube behind the torpedo, forcing it out in a flurry of bubbles. As it exits, the torpedo's internal motor is ignited and the compact but powerful engine engages its tiny propeller and sends the weapon in a straight line towards its target at a speed of some 35 knots.

Suddenly sensing danger, Stoker stops watching the torpedo's wake and instead swivels the periscope in a quick arc. There on the port side ⦠a

destroyer

intent on ramming! Stoker instantly gives his next order: âRed Green 270 close. Destroyer ⦠emergency dive ⦠10 down ⦠keep 70 feet.'

44

The orders are confirmed and, only an instant after they have submerged, they hear it â¦

âAmidst the noise of [the enemy cruiser's] propellers whizzing overhead, was heard the big explosion as the torpedo struck.'

45

Bullseye!

Alas, if the torpedo has caused the immediate devastation that Stoker thinks it has, it means that right in front of them right now there will be either the sinking cruiser or the mines it has dropped or both, which is why he immediately gives his next order: âPoint to starboard.'

46

Three minutes after that danger has passed, he tries to get back on the straight and narrow of the Narrows. Stoker walks across to the chart table, where Lieutenant Cary has marked their progress in red crayon. âPort 5 steer 010.'

47

But now another problem. Helmsman Charlie Vaughan can no longer read the gyrocompass. It has been tripped off its axis by the explosion. âVery good,' says Stoker. âSteer by magnetic compass.'

He remains calm but knows they are in trouble, for the magnetic compass, near so much metal, is notoriously unreliable. The devastating denouement does not take long, for the submarine is effectively blind amid terrible swirling currents and ⦠with a sudden crash, the sub hits the banks of the eastern shore.

Oh ⦠Jesus and Mother Mary ⦠have

mercy

.

From six fathoms down, the sub quickly slides up to just a fathom below the surface, meaning the whole bridge and conning tower are now above water. And still it gets worse. For when Stoker puts up the periscope once more and swivels it around, he is confronted with that acute blackness that is the blackness of the muzzle of a cannon looking straight back at you, and it suddenly fires! All of it is so instantaneously confronting that Stoker jumps backward.

The sub has hit the bottom directly below the guns of one of the ancient forts that stand on the shoreline. âWith the boat apparently fast aground,' Stoker would later recount, âand a continued din of falling shell, the situation looked as unpleasant as it well could be â¦'

48

Aghast, Stoker looks through the periscope and reports to the crew that, âThe sea is one mass of foam caused by the shells firing at us.'

49

And yet, even in the midst of catastrophic misfortune, every so often Lady Luck can still wink at those whose pluck she admires â¦

For so close is

AE2

under the fort that the angle is too steep for the guns to fire down upon it.

Stoker stands like a rock in the control room. Whatever else, he must project calm. âFull astern,' he orders.

A senior sailor at the main switchboard on the port side of the control room, standing a few feet from Stoker, instantly complies. âFull astern, aye aye, sir.'

50

There is a grinding sound but no movement. Clearly, the propellers are cutting into the muddy bottom, but Stoker does not care. âWe have to get off,' he says grimly, âwhether the propellers get damaged or not.'

51

They keep going, rocking back and forth.

âFull ahead.'

âFull ahead, aye aye, sir,' the sailor confirms, twisting the dial on the glowing panel in front of him in the opposite direction. Every movement is measured.

âUp half ahead.'

Then, 30 seconds later, âGroup up full ahead, sir.'

Stoker waits. They all wait.

They can all hear the twin screws thrashing the water.

There is tiny movement.

âGeoffrey, please pump ballast to the aft tanks.'

52

The Executive Officer, Geoffrey Haggard, passes the order, sending three seamen to switch the pumps into action and open valves that send water through overhead pipes from the bow to the rear of the submarine, causing her to be heavy aft. Like a seesaw, one end has a tendency to sink with the extra weight.

âReverse motors. Group up full astern.'

53

This time, deliberately unbalanced, the submarine is pulled backward into deeper water by her twin screws.

They are still alive!

Soon at a depth of 70 feet, Stoker has her âon the port propeller, helm hard a-port',

54

with their nose soon pointing for the open sea and safety. And yet, to continue on that course would be against orders. They have been told to run amuck, and successfully torpedoing one cruiser does not quite qualify. No matter that they can hear the endless swish of angry propellers from the ships roaring back and forth on the surface looking for them, Stoker now tries to turn the sub back up the Narrows, making allowance for the four-knot outgoing current and â¦

And BANG! Now they have hit the western, European, shore, where else but 'neath another Turkish fort, this time at a depth of just eight feet!

Up periscope, for a 360-degree swivel, of which 300 degrees is pure horror ⦠and the rest ⦠wonderful. For there is the fort firing down upon them; a gunboat closing fast and blazing hard; several destroyers firing broadsides; and ⦠a âclear view up the strait showing that if we could only get off we were heading on the correct course'.

55

A-whump ⦠a-

whump â¦

a-WHUMP.

There are perhaps few things more terrifying than being in an exposed submarine hearing, as Able Seaman John Wheat would recall it, âthe shells striking the water and bursting outside',

56

but at least the Commander does not seem to feel it. And at least this time, the cursed current, which to this point has been a nightmare to deal with, now offers a surprising bouquet to providence by swinging the boat's stern around to port and bringing the bow angled down, at which point Seaman Albert Knaggs would confide to his diary, âWe could hear inside the boat the shrapnel dropping on us like a lot of stones.'

57

Still

they are alive, however, and they might have a chance to get off, after all!

âGroup up all ahead, both motors,' Stoker crisply commands.

58

The twin electric motors whirl, the propellers thrash and the submarine shakes heavily under the strain, as the shells above find their range â A-WHUMP, A-

WHUMP

, A-WHUMP. But again, miraculously, four minutes after hitting the bank, there is movement.

AE2

is slipping back down the bank, admittedly with a terrifying grinding noise coming from both propellers and then two massive bumps from something unknown hitting the sub ⦠but they'll take it.

Dacre Stoker's plan of conserving battery power, however, has been swept aside by the two calamities. Worse, seawater is found seeping into the bilges. If seawater makes contact with the batteries stored under the decking, then chlorine gas will fill the submarine and everyone on board will die very quickly, choking on the fumes, with their skin, eyes and lungs burning as they asphyxiate. (A torpedo would be kinder.)

Whatever else, at least the submarine is now submerged. On the surface is certain death in the darkness, whereas 'neath the waters of the Dardanelles it is only likely.

âFive degrees downward, make your depth 70 feet,' Stoker commands,

59

as

AE2

continues to move up the Straits to the Sea of Marmara. Hopefully.

On the shores of Gallipoli, the Anzacs continue to be devastated by shot, shrapnel and shell. As to quelling the latter, Charles Bean would be quick to note, âthe ships' guns, upon which Churchill had counted with such complete assurance, were so useless in such a situation that they had almost ceased to fire'.

60

The problem is that Australians and Turks are so mixed up now it is impossible to tell which is which, and the ships risk killing their own if they fire on any but the most distant targets. Yes, the covering force has some red and yellow flags to indicate their position, but the problem is that those flags are also a target for the Turkish artillery. A further problem is that it is impossible for those in the ships well offshore to determine just where the Turkish artillery is.

The one shining light in this dark tale is the armoured cruiser

Bacchante

, whose Captain Algernon Boyle, in response to the urgency of the situation â and the difficulty of spotting where the Turkish artillery is â guides his ship right to the point that it nudges the shore, gets a bead on a particularly troublesome small battery upon Gaba Tepe and, for the moment, manages to silence it.

61

âI can never speak sufficiently highly of the navy,' General Birdwood would note, âfrom admirals down to able seamen. The whole Anzac Corps would do anything for the navy ⦠Our men were devoted to those ships and their crews, and will always remember the British Navy with admiration and devotion.'

62

Aboard

London

, as with all the other battleships, two things keep coming from the shore. The first is requests for artillery fire, in those areas the Turks are fiercely defending â and it is for this reason that most of the battleships now lie parallel to the shore, as they fire in broadside after broadside.

And the second thing coming from the shore is boats of terribly wounded soldiers, arriving in an endless stream of blood. The one fully equipped hospital ship,

Gascon

, is quickly filled to capacity, as are the two transports catering for the lightly wounded, and it is soon for the other ships to take the wounded on and cope the best they can.

âAs usual, with the start of all British expeditions,' Ashmead-Bartlett would record, âthe medical arrangements were totally inadequate to meet the requirements of the hour. Optimism had minimised our casualties to the finest possible margin, but the Turks multiplied them at an alarming rate. Apparently there was no one in authority to direct the streams of wounded to other ships where accommodation could be found for them, and many were taken on board the warships.'

63

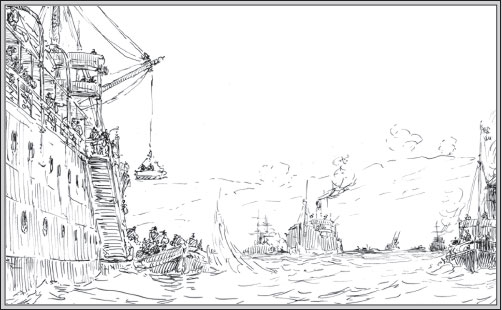

âBoarding the Hospital Ship', by Ellis Silas (AWM ART90793)

Finally, however, a clear order: the wounded are to be taken back to the empty transports whence they came, where as many doctors as can be spared will also be sent, and the ships can take them back to Egypt.

General Bridges remains stunned. Having stepped ashore at 7.20 am â accompanied by his Chief of Staff, Lieutenant-Colonel Cyril Brudenell White â he had found all over the beach dead and dying men. All had been chaos and confusion. Shrapnel raining down. Not a single officer there to greet or brief him. No one in charge.

At General Bridges' headquarters, being constructed just back from the beach, a worrying series of messages from a flaky and clearly receding frontline are waiting for him. MacLagan reports they are being heavily attacked on the left (5.37 am), another message reads 3rd Brigade being driven back (6.15 am), and then another recent and urgent one from MacLagan says, 4th Brigade urgently required (7.15 am).

64

What to do?