Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash (14 page)

Read Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash Online

Authors: Edward Humes

Tags: #Travel, #General, #Technology & Engineering, #Environmental, #Waste Management, #Social Science, #Sociology

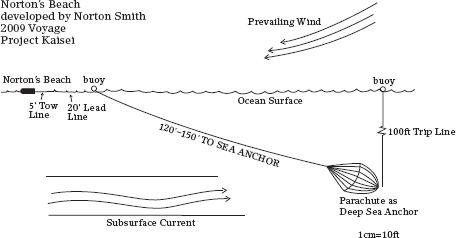

The

Kaisei

crew released the device and let it do its thing for nearly eleven hours, during which time the currents and parachute moved it more than three nautical miles. When The Beach was retrieved, Smith found that the net was full of small plastic particles and almost no sea life—the contraption worked.

An armada of such devices would be substantially less costly than more traditional, fuel-intensive methods of gathering the plastic, but would still be extremely time-consuming and expensive. The Pacific gyre would take about sixteen years and nearly half a billion dollars to clean up in this way, he figures—a daunting prospect at best. And he also makes clear, as does Crowley, that such a massive effort would quickly become a pointless exercise without something else even bigger happening at the same time: a worldwide reduction in disposable plastic garbage, and an end to the constant flow of plastic that goes missing every year, and ends up as marine chowder.

Crowley was still thrilled with the testing. For a first attempt, Smith’s ideas showed promise, though she understands these sorts of technological solutions are a long way from being ready for prime time—if they are ever ready.

In the meantime, finding ways to encourage the removal of some of the largest and most dangerous pieces of ocean garbage—the tens of thousands (perhaps hundreds of thousands) of “ghost nets” adrift in the ocean—should be a top priority, Crowley says. These nets aggregate thousands of pounds of trash, they become caught on coral reefs, then break them apart during storms, and each one can entrap dozens, sometimes hundreds, of fish, birds and sea mammals. The

Kaisei

encountered quite a few on its voyage. Capturing derelict nets sometimes required most of the twenty-person crew to engage in a kind of tug-of-war as they hauled in the enormous, twisted lattices of plastic festooned with trash and barnacles on board, cutting parts of it with a torch in order to wrestle the thing out of the water, so weighted down was it with trash and dead creatures it had snared. There are thousands of tons of such abandoned ghost nets rolling through the gyre, giant marine death traps. No accurate global inventory exists for ghost nets, although the numbers even in small areas are staggering: three thousand estimated to be loose in Puget Sound alone; 1,800 removed from waters off Hawaii in recent years, without putting a dent in the problem.

Several pilot programs around the world have had success in paying fishermen to catch these nets in lieu of trawling depleted fisheries; Crowley advocates permanent and larger-scale programs to put fishermen to work undoing the damage ghost nets cause.

Beach cleanups also help, she says, because removing the trash from the surf cuts off a major source of “food” for the garbage patches.

This dovetails with the final part of Project Kaisei’s mission: education and media, getting the word out about the problems of oceanic trash and plastic pollution. Crowley brought a documentary film crew, live bloggers and journalists with her aboard the

Kaisei

during the expedition, documenting the trash and the nascent efforts to combat it. Awareness, she says, is the best weapon against the trash, and the best goad toward action.

“I want everyone I can possibly reach to understand what we experienced on this voyage, what a very disturbing experience it was to be in the middle of the ocean, where one should be finding pristine oceanic wilderness, where there’s nothing but ocean on all your horizons, a place that to me is full of wonder, and you are seeing our own garbage. You see laundry detergent bottles and bleach bottles, children’s toys, toothbrushes, plastic buckets, storage containers, packing straps. All this stuff out there in the middle of the ocean, it just makes me sick. And I want everyone to feel that, too.”

It turned out this part wasn’t so hard. She has found that ocean trash is a unique environmental issue. It is that rare green cause that transcends politics and ideology—once people see and understand it. Garbage floating on the waves, it seems, has the power to unite. Ten thousand visitors showed up at the docks in the days after the

Kaisei

’s return, eager to tour the ship and see the array of trash and ghost nets that the crew put on display on the deck, to learn about the gyre and to hear how that distant place was full of all of our trash.

“I’ve never talked to anyone who has seen the pictures or the video we’ve brought back, or who came to the ship to learn what it’s really like out there, who then says, ‘I don’t care.’ That’s why I’m hopeful.”

6

NERDS VS. NURDLES

T

HE SCIENTISTS TRYING TO FIGURE OUT THE

jabberwock-sized problem of the gyre garbage patches tend to be characters. Miriam Goldstein is no exception.

Goldstein came to the work at Scripps after a post-college break from academia that included stints as a construction worker, an environmental consultant, a naturalist at New Hampshire’s Mount Washington and a salesperson at a biological curiosity shop in Soho called Evolution. Now she represents a new generation of ocean researchers eager to launch their scientific careers by uncovering the extent and consequences of marine plastic pollution.

Goldstein is, she says, part of a new army of nerds taking on the legions of nurdles. “There’s a lot we don’t know yet, and it will take years of study to really get a handle on the extent of the problem and its impact,” she says. “But we don’t need to know everything to know that we should stop putting trash in the ocean. We already know that should stop.”

She tends to see the state of the sea as the ultimate in societal heedlessness—an unintended and untended lab experiment run wild, in which the world finds out just what happens when we dump fifty years’ worth of plastic into the ocean. Now, Goldstein says, it’s time to assess the damage and figure out where to go from here. As part of that effort, she has been on extended sea voyages four times in less than two years, gathering data for Project Kaisei, Scripps, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the most fitting acronym in government) and her own dissertation on the impact of plastic micro-debris in the North Pacific. Her work is part of the ground-floor research finally being done systematically on ocean trash after a decade of being left to a few capable but extremely shorthanded mavericks and gadflies.

In an ocean culture dominated by old salts with tan and craggy faces, the fair and freckled Goldstein seems the unlikeliest of oceanic heroes, quite the opposite of veteran sailor Mary Crowley, who thinks storm-swollen seas are a fun sort of challenge. The young scientist, by contrast, describes herself at sea as an “accomplished barfer.” To her credit (or, according to her family, as evidence of her insanity), she charted her professional course despite knowing her landlubber tendencies, revealed during her very first sea voyage. This was a half-day whale-watching excursion off the coast of her native New Hampshire, which she organized at age ten, dragging her reluctant sister, brother and parents along as she pursued her passion.

“Let me just say, we’re not really a very outdoorsy family,” she recalls with a laugh. “The entire family spent the entire time barfing over the rail. We have pictures of the four of us lined up.”

For her doctoral studies at the University of California, San Diego’s Scripps Institution, she prudently planned to focus on coastal pollution, which would have safely limited her sea excursions to knee-deep wading into tide pools. That changed in 2008, however, when she started reading about the gyres, the garbage patch and ocean plastic—and how little we really knew about it. She proposed that the University of California Ship Fund devote some of its grant money and research vessel time to studying the matter, which the institute honchos soon agreed was a good idea, leading to the August 2009 SEAPLEX voyage (Scripps Environmental Accumulation of Plastic Expedition) to the garbage patch. The only caveat: Goldstein, queen of the tide pool explorers, had to take charge as chief scientist and see her idea through, an intimidating but unrefusable opportunity that knocked the twenty-five-year-old ocean scientist out of her wading boots for good. Initially planned for two weeks, the voyage was expanded to three when Project Kaisei offered to provide a second ship and more financing for an in-depth look at deep-sea ocean plastic.

The journey shattered Goldstein’s expectations and ended up shocking her whole team despite weeks of burrowing through piles of reports, papers and news clippings she thought would prepare her for what lay ahead. She and her colleagues had spent long hours planning the trip, obsessing on how they were going to find the trash, and what they would do if they started roaming around this vast ocean desert without finding anything. It’s a big ocean out there, they kept reminding one another. You can go out looking for something and the weeks can fly by—and then you come up empty. That was Goldstein’s fear as the 170-foot

New Horizon

left port in San Diego. She knew marine biologists who went to sea time after time looking for certain organisms or feeding patterns or weather phenomena, and they just never found them. This was the oceanic equivalent of one of those space launches in which the parachute doesn’t open or the radio goes dead or the probe drifts off into space without ever establishing contact with mission control. Things are spread out at sea, and the ocean seems to delight in frustrating scientists and crushing their attempts to uncover its mysteries.

So Goldstein and her colleagues were taken by surprise when it turned out to be all too easy to find the garbage at sea. As it happened, they simply set course for the gyre and the trash found them. They had been conditioned by press reports and the very name—Pacific Garbage

Patch

—to expect an actual patch, a visible aggregation of garbage, which news story after news story described as a kind of floating island of debris twice the size of Texas. But they did not find a bunch of trash in one place. What they found were high concentrations of small plastic bits spread across the entire 1,200 miles of ocean they traversed and trawled, finding plastic in every net. Jellyfish and sea slugs would come up in the net, swimming amid the plastic. Inside the jellies, plastic could be seen through their transparent bodies. It was far worse than they had imagined, not an island, but that damn plastic chowder. And it was everywhere.

“After days of endless plastic,” Goldstein recalls, “we were all getting really depressed.” But the prevalence of plastic had a silver lining. Finding it meant they had a good shot at understanding it. Three grueling, thrilling weeks followed of water sampling, manta tows (a special net shaped roughly like a manta ray deployed on the side of the ship), microscope work, plankton preserving (rotting plankton, Goldstein says, is not a smell you want to experience if at all possible) and captures of plastic debris small and large.

Goldstein’s primary interest is how the unusual critters that live in the gyre, most of them small and many of them microscopic, interact with the debris and plastic in their midst. Do they peacefully coexist? Is it poisoning them? Do these added surfaces to cling to and lay eggs on—in an area of the sea where there is no land for a thousand miles—give a leg up to some creatures in the ecosystem at the expense of others? And what happens if those tiny crabs, barnacles and other opportunistic hitchhikers cling to a hunk of plastic and get swept by the gyre to a place where they don’t belong? Nature’s fragile balance, its chains of prey, predator and symbiont, could be altered by the plastic taxi service. Preliminary evidence from the expedition, Goldstein says, suggests this is exactly what’s happening, though the degree of benefit and/or harm to various species will take years of study to work out.

Goldstein has an answer for those who might shrug and wonder if such questions really matter in the grand scheme of things. In a word: yes. And here’s why: Half the oxygen we breathe emanates from microscopic phytoplankton sloshing around the surface of the ocean. After literally billions of years of performing that essential, priceless service, those vital organisms now must swim and feed and survive in a sea of plastic soup. Figuring out what’s up with those organisms is, Goldstein suggests, a pretty vital matter. If we are inadvertently killing them off, the result could be far less visible, but even more devastating, than deforestation.

The other big questions that the SEAPLEX/Project Kaisei expedition sought to explore were equally compelling:

Now that we know that one in ten lantern fish has ingested plastic, what is this new part of the fishy food pyramid doing to these vital creatures that the rest of the food chain depends on? Many plastics can leach potentially toxic chemicals over time, particularly as the plastic begins to break down from the action of weather, wind and wave. Is that happening, and with what effect?

Are plastic particles acting as collectors of toxic chemicals, transporting and concentrating what is known as POPs—Persistent Organic Pollutants? This is the opposite of the leaching problem—plastics not giving off toxins, but acting as magnets for even worse chemicals. Pesticides, chemical fertilizers, half-combusted fuel, solvents and other man-made pollutants roll and rain into the oceans every day by accident and by design, and many of these chemicals are hydrophobic. That is, they hate water, won’t dissolve in it and just wait for something better to come along that they can stick to. Weathered, cracked, sea-scoured bits of plastic become sponges for these POPs, and this is not a good thing. Yes, the plastic can take the chemicals from the water, but then little fish eat that plastic, and a chain reaction called bio-magnification begins.

This is the scenario the researchers are trying to gauge to see if it threatens marine ecosystems and human food safety: Let’s say the little fish eats ten tiny pieces of POPs-infused plastic. Then a bigger fish comes along and eats ten of those tiny fish. Now we have a fish that has imbibed the equivalent of one hundred contaminated pieces of plastic. Then a bigger fish eats a bunch of those, and so on up the food chain, with the chemicals becoming progressively more concentrated in the larger sea creatures. This is bio-magnification. At some point, some of those larger creatures end up in the seafood case or the canned goods aisle at your local supermarket. We simply don’t know what that means, but if Goldstein’s team has its way, we will know in a few years.

“We just might not like what we learn,” she says.

Even the most basic questions about the trash-ocean interface still await answers. The Scripps researchers are trying to accurately estimate the true size and concentration of the debris in the Pacific Garbage Patch and, more to the point, whether or not it is growing over time. The data is mixed on this: Observations in the Pacific by other researchers suggest the plastic has increased since the 1990s, even doubling in some areas of the patch. On the other hand, the largest collection of data from water samples in the North Atlantic gyre—twenty-two years’ worth made by students on training voyages with the Sea Education Association—show that the plastic concentrations have held steady there, against all expectations. Researchers had assumed that, since plastic production has more than tripled in the past twenty-two years, there should be more plastic in the ocean, rather than the steady state it seems to have achieved (in the Atlantic, at least). Is there some mechanism removing the plastic—unknown currents, chemical reactions, plastic-eating microorganisms? Or is there really more plastic there despite the data, uncounted because it has broken down into such small particles that it remains undetected?

To help answer this, the Scripps researchers are doing two things: supplementing their manta tows with data from bucket samples from the gyre, and trying to figure out how plastic at sea ages. This latter problem is tougher than it sounds. Unlike archaeologists, who can carbon-date artifacts, or paleontologists, who can infer the age of a dinosaur bone from the geologic strata in which it was buried, the ocean plastics investigator has no way of telling the lineage of a 5-millimeter bit of plastic. The stuff has no chemical signature, no provenance, no forensic trail. It could be a year old, five years old, fifty years old—you just can’t tell. In a landfill, you might infer the age of a piece of plastic from the junk it’s buried with, the same as a geologist (

Oh, that hunk of blue polystyrene is sitting on top of a June 1973 edition of

Life

magazine—could be a clue!

). Ocean-borne plastic bits offer no such context. So Goldstein has pools of seawater filled with plastic baking in the sun and cooling at night on her lab roof back in San Diego, trying to come up with an age gauge for marine plastic debris. She’d like to run this experiment for two years or so; her professors told a stricken Goldstein they think it would be better to keep it going for two decades. Like landfills, she says, ocean plastic research is forever.

Everything about ocean trash is not a question, however. Here’s what we do know: The United Nations estimates that a minimum of 7 million tons of trash ends up in the ocean each year, 5.6 million tons of which (80 percent) is plastic. The Sea Education Association data from the North Atlantic Gyre suggests that plastic concentrations in the ocean waters of the major gyres can easily reach 130,000 or more pieces per square mile of ocean surface; one survey of the Pacific Garbage Patch zone found concentrations nearly three times that level. The 5 Gyres research group, meanwhile, estimates that the total plastic content of the gyres exceeds (probably by a lot) 157 million tons, equal to 63 percent of all plastic made in the world in 2011. The group considers that estimate to be extremely conservative.

Even so, that’s a big bag of plastic. It would take 630 oil supertankers to carry that much plastic. By contrast, the British Petroleum Gulf of Mexico oil spill in 2010, the largest maritime environmental disaster in history, released an estimated two-thirds of a million tons of crude oil. That whole oil spill could fit on two and a half supertankers.

To be clear, all of these ocean plastic numbers are at best educated guesses so far, based on slices of data collected from small sections of the biggest geographic feature humans will ever experience. There is a great deal of mystery left in that most ancient of things, the ocean, its newest resident, plastic, and how the two combine. A lot of the numbers and “facts” repeated in news coverage—claims that a hundred thousand marine mammals are killed each year from ocean plastic, that 80 percent of the trash at sea is from land sources rather than ships, that there is an actual garbage island looming somewhere in the Pacific—have no known sources with any credibility. The myth-making is a distraction, Goldstein worries, because the made-up information could erode the credibility of real science, and also probably understates the true problem. The research needed to firm up the data and answer the big questions is just barely getting under way.