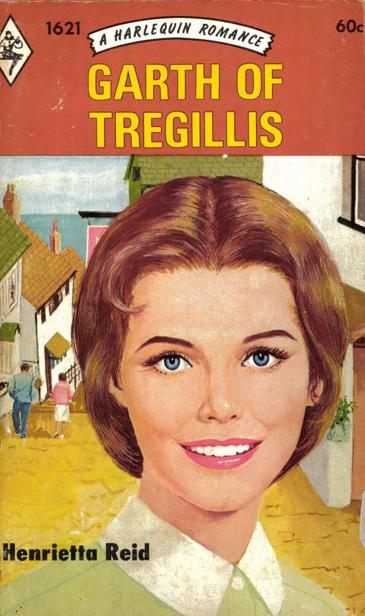

Garth of Tregillis

Read Garth of Tregillis Online

Authors: Henrietta Reid

GARTH OF TREGILLIS

by

HENRIETTA REID

To Garth Seaton, master of Tregillis, Judith Westall was only the governess he had engaged to look after the two children in his care.

But Garth did not know that Judith’s

reasons for coming to Tregillis had nothing to do with her job ...

I STOOD at the doorway of Diana’s bedroom and gazed about.

Somehow, although it had been several days since Mr. Lloyd, the solicitor in charge of Diana’s affairs, had told me I was her heir, I hadn’t really accepted the fact that she was dead. I think it must have been the light film of dust that lay over the furniture in the bright, spacious bedroom, the flower-spattered lawn dressing-gown folded neatly over the brocade-upholstered bedside chair just as she had left it, the orderly array of make-up bottles and perfume flasks, that brought home to me with stunning force the realization that a part of my life was finally and irrevocably over. It was as though with Diana Seaton’s death in a car crash a brightly illustrated book had slammed shut, leaving me confused and disorientated.

Reluctantly I crossed to the small writing-desk where Diana had kept all her correspondence. This was something I had put off as long as possible: I was loath to pry into her affairs, feeling mean and covert as I inserted the key in the gleaming, sloping lid.

Although I had known her since schooldays there was a part of her life she had been reluctant to discuss with me—the years she had spent as a child at her father’s beautiful home in Cornwall. She had not spoken much of Tregillis, but I had seen glossy pictures of it in the magazines and knew that it was a great majestic Tudor pile with long mullioned windows and tall chimneys.

After the holidays she would return to the school at which we both spent our childhood, grave and uncommunicative, her quietly gay spirits subdued as though her stay at home had subtly matured and changed her, so that she appeared reserved and disconcertingly grownup, and it was not until some days had passed that she would regain her good spirits.

Only once had she confided in me, and that was during the last few days of our school life together. We had been sitting up in bed whispering to each other in the sleeping dormitory, exchanging our plans for the future—or at least I had told her mine. It was not until I had excitedly talked myself out that I noticed that she was not reciprocating. In the moonlight that slanted through the window I could see her sitting up in her narrow white bed, her chin resting on her hunched knees, her pale face shadowed and enigmatic.

‘Lucky you,’ I said enviously, ‘I suppose you’ll return to that wonderful home of yours and have a fabulous time, with all the local men queuing up. I expect your father will hold a ball for you,’

I added, enthusiastically improvising, ‘and you’ll float down that wonderful wide staircase looking stunning in some frothy confection.’

She had given a low ripple of laughter that held no amusement.

‘You’re letting your imagination run away with you—as usual, Judith. You’re wrong, you know. I shan’t be returning to Tregillis—not really. Oh, I’m going back for a short holiday, but after that I’m going to London and probably I’ll never see it again.’

I had stared at her in stupefaction. ‘But why? It’s your home, isn’t it? And you love it: I can tell that.’

There had been a long pause. A cloud had passed over the moon and I could no longer see her face and I wondered if I had impulsively trespassed. Then she said slowly and reluctantly,

‘Mummy and Daddy are separating. Oh, there won’t be a divorce, or anything like that! Mummy’s leaving; taking a house in London.

They simply never got on—not even when I was a tiny child. They used to have the most dreadful rows—quiet, bitter, horrible rows, not loud or violent, for Daddy’s one of those reserved, self-contained men. I’m rather like him actually. He loves boating and fishing and taking long solitary walks. But Mummy’s different: she’s full of vitality and likes gaiety and parties and having lots of friends around her, all chattering together. I think that’s probably why they never got on. She expected Daddy to be a social success and he hated it all and didn’t hide it, and Mummy would get angry and say he did it deliberately and was trying to put her at a disadvantage. Yet people say that one should marry one’s opposite to be really happy,’ she added wonderingly. ‘If I ever fall in love, Judith, I’ll try to make it be with someone as much like myself as possible.’

‘But—but why on earth should that mean you’re leaving Tregillis?’ I had asked in bewilderment. ‘You say you get on with your father, and understand him.’ What I actually meant was, why was she flinging in her lot with her mother, with whom she had little in common, when her heart was so obviously in the life she led at Tregillis. But I had hesitated to put it into words.

But Diana had understood, with that quiet maturity that made her seem so much older and wiser than I, although there was only a few months between us. ‘Mother’s ill,’ she said, her voice sombre.

‘She hasn’t been keeping well for some time. She’s grown so thin and haggard. Daddy wanted her to see a doctor, but of course she refused. She was always so healthy, so vital, that I suppose it seemed ludicrous to her. But in spite of her objections, in the end Daddy sent for a specialist.’ She paused, then added defiantly,

‘Afterwards I heard what he said to Daddy. I deliberately eavesdropped.’

I had felt faintly shocked at this revelation. Diana had always seemed to me completely admirable and I was childish enough then to feel disappointment.

‘Oh, I know you’re thinking it was a rotten thing to do, but you see I simply had to know, for I’d planned to stay with Daddy as soon as I knew they were separating. My mother asked me to go with her and I refused. I hated, every bit as much as Daddy, the life she was planning in London. I’m just not cut out to be a social butterfly. It’s not the sort of life I want. But when I heard what the specialist had to say, of course it changed everything.’

Now as I turned the key in her desk I could remember the desolation in her voice.

‘I heard him tell Daddy that Mummy had not long to live but that she should go ahead with her plans and take a house in London. She would be happier that way.’ Her voice broke. ‘It was so horrible. Poor Daddy was so broken up, so helpless and unlike himself! Then, that night, he asked me to go with Mother. He explained that he wanted me to stay with him so much, that we were always so close, but in his own way he always loved Mummy and he told me it would comfort him to know I would be with her.

So this time when I leave Tregillis it will probably be for ever.’

Then, to my horror, she had broken down in deep choking sobs that she had done her best to muffle in the bedclothes.

Slowly I pulled back the lid of her desk. I don’t really know what I expected to find, but I was reluctant to go through those neatly stacked papers in their partitions. Everything was orderly and in its appropriate place—but then that had been typical of Diana Seaton. We had been so very different in temperament.

Afterwards, when our schooldays were over and we had gone our separate ways, I had been surprised and delighted to hear from her once again. A letter had been sent to my home address, then re-directed to me at the bedsitter I had taken in London when I had decided on taking a language course in the Berlitz School. I had always wanted to travel—to see the world—and becoming a courier for a tourist firm had seemed to me the most practical way to fulfil my ambition.

I had thought I would be too busy with my studies to feel lonely, but I found it wasn’t so. London seemed a strange and lonely place after life in a small provincial town. That’s why Diana’s invitation had pleased me so much. We had always got on so well at school and there was no reason why we shouldn’t continue the friendship now that Diana was, like myself, alone in the world. She had mentioned—in passing, as it were—that her father had drowned in a boating accident. Her letter had been strangely laconic, as though she were giving me a summary of something that in no way touched on her own life. I found this cold, unemotional statement of fact disconcerting and slightly disturbing. Her mother’s death, of course, had been expected and no doubt before it had occurred she had become adjusted to the prospect.

But the death of her father, Giles Seaton, was a completely different matter. I knew how she had loved him and her beautiful Cornish home and I remembered how, once when we were at school together, she had said fervently that she wished she had been a boy so that she could live at Tregillis always. As matters stood, the family home would pass to her cousin, Garth Seaton, who was her father’s heir.

I had written to her immediately, eagerly accepting her invitation, and had looked forward to renewing our friendship. But when I first joined her I found her manner strange and oddly secretive and I had realized then that the tone of the letters she had sent me was only too expressive of the change that had occurred in her personality. For what had been reserve before had now developed into a cold withdrawal. Often when I returned in the evenings I would come upon her in the dusk curled up in an armchair, sunk in a brooding silence, so that I had begun to wonder why on earth she had asked me to join her in the first place. I felt embarrassed and ill at ease. Did she regret her invitation, I had wondered, and long for me to realize that I was not wanted?

I had brought the subject up one afternoon when I had returned from a class. She herself had only come in and still wore her beautifully cut and expensive suit. Unlike myself, Diana had always been extremely fastidious concerning clothes. Even when we had been at school together I had never seen her ungroomed or carelessly dressed. That was why I was dismayed to see her hunched up in an armchair, her clothes wrinkled, her hair dishevelled, as though she had agitatedly pulled her long, slim fingers through it.

I sat down in the chair opposite her. There was no use in putting it off any longer: now was the time to find out if Diana wanted to get rid of me. If she regretted her offer it was as well I should know it at once, rather than later, when the tension between us had become unendurable.

I had tried to broach the subject as tactfully as possible and was utterly amazed at her reaction.

‘Of course I love having you here. I shouldn’t have asked you unless I wanted you. You know me well enough for that.’

It was true, of course: Diana had always been utterly straight and forthright in her dealings with me : subterfuge was foreign to her nature. I felt a surge of relief. Then what could be causing Diana such misery and agitation? I felt sure it wasn’t an unhappy love affair because, although Diana had swarms of young men ringing up at the most unlikely hours, she treated them all with the same almost absent-minded indifference. It was fairly obvious that she had not fallen in love. When she did, of course, it would be an entirely different matter, but I had known that whatever was troubling her at that time it was certainly not a broken heart.

I had gazed at her pale face and reddened eyes, puzzled yet loath to put the direct question.

Then with a sudden lithe movement she had jumped to her feet and had begun to pace the room, running her hands through her hair with a nervous gesture that I had never seen her use before.

‘Must you keep looking at me like that?’ she had said irritably, ‘as though I’d suddenly grown two heads!’ Then, immediately she had been contrite. ‘Sorry, Judith, I know I’m being a beast, but I’m frightfully worried about something.’

As I was about to speak she said quickly, anticipating me, ‘It’s not the sort of problem anyone can solve by sage advice. In fact, I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s one of those nagging unsolvable mysteries that haunt one all one’s life.’

As I reached down and took a bundle of papers from one of the slotted partitions in her desk I remembered the poignancy of her voice. All her life! And yet her life had been so tragically short!

But at the time I had been struck by her defeatist attitude. ‘You know that’s nonsense,’ I had protested. ‘Every problem can be solved—or at least clarified—if people talk it over together.’

She shook her head and for a moment I thought she was going to refuse to discuss it. Then she said slowly, ‘It’s something Cousin Eunice said. I don’t think it would have entered my mind, but hearing her put it into words and seeing him afresh after a few years— it made all the difference.’