Gentlemen of the Road (8 page)

Read Gentlemen of the Road Online

Authors: Michael Chabon

Tags: #Fantasy, #Travel, #Modern, #Contemporary, #Adventure, #Historical

“Late as usual,” Amram said.

CHAPTER SEVEN ON THE SEIZING

ON THE SEIZING

OF A LOW MOMENT

H

anukkah had been kicked awake by worse men, among them his own father, and so the curses he muttered, with his eyes shut and the honeyed hand of a dream still caressing his thigh, extended no further into history than the African’s great-grandmother and confined themselves to envisioning her use by scabby Pecheneg stallions, making only glancing reference to the attentions of Bactrian camels. The true object of Hanukkah’s spleen was wakefulness itself and the world that it would oblige his five outraged senses to certify. Hanukkah had soldiered in the army of an empire at peace and had thus dealt and witnessed death only in small batches, and he was shocked by the scale of slaughter he had seen today, wrought by foreign invaders against Khazar men and women like him—children of Kozar the son of Togarmah the son of Gomer the son of Japheth the son of Noah—“people of the felt walls,” burners of dung fires, sworn to the solitary god of the clear blue sky, whether that god was called Tengri, Jehovah or Allah. Most of all he was shocked by the pointless butchering of a stranded Rus, mute, dazed and trembling with some fever, white as a fish belly, who was dragged by the Arsiyah from his hiding place and slashed open like a gushing sack of wine. After that, Hanukkah curled up on the steps of the mosque and withdrew into sleep and his dream of Sarah, of the faint smell of burning sandalwood when she took his head into her lap, a dream from which Amram’s toe now dislodged him with all the tenderness of a boathook

Hanukkah sat up, and opened his eyes, and saw amid the smoke, dust devils and steady snow of ash a gaunt, bloodied figure, tottering, asleep on his feet, his black cloak crusted and dragging behind him, the air around him wavering in a madness of flies.

At the sight of the Frank who had saved his life, Hanukkah felt something swell inside him, like the bladder that kept a sturgeon buoyant and swimming true in the dark of the Khazar Sea. Men could be broken more terribly than he had ever imagined; but they could also be repaired. Hope was a powerful cordial, and for a moment, with the burn of it at the back of Hanukkah’s throat, he could only stand there, barking like a goose. Then he wiped his face on his filthy sleeve and hurried to Zelikman’s side.

“Sit,” he said, “please.”

He sat the Frank down on the steps, pulled off his boots and fetched some water from a cistern. Some of the water he mixed with wine and passed to Zelikman in an overturned steel helmet. The rest he used to wash the blood from Zelikman’s hands and face and to bathe his feet. From this mild and voluntary act of self-abasement, from the routine business of cistern and dipper and the wringing of a cloth, from the Frank’s pale feet with their surprisingly soft ankles, Hanukkah derived a measure of comfort and regained his spirits. He found a neglected passage behind the mosque that the Rus had disdained to plunder, and in a cellar there a pair of toothless old sisters who at extortionate prices provided him with cold porridge, some lentils and mint, a bag of apples and the butt of a lamb sausage. He gave the food to Zelikman, who ate, and drank, and rested, talking to the African in Greek or Latin.

The subject of their conversation appeared to be Filaq, who sat slumped on the steps of the mosque with his chin in his hands, wearing a mask of tear streaks and ash. The stripling had scarcely moved in the hours since the Arsiyah mercenaries had paroled their prisoners to shift for themselves, saying nothing at all for what struck Hanukkah as an abnormally long period of time. With his smudged cheeks and staring eyes he seemed younger than ever, a child with an empty belly too weary to sleep. He did not appear to notice when the Arsiyah at last came trudging out of the mosque and clattering down the steps around him, stooped as by time or a heavy load, their gait uncertain, their evening lifting of their voices toward far-off Mecca having done little to ease the painful knowledge of their failure to defend this Muhammadan town from destruction by the Northmen. They loitered in the square, cast down, aimless. Their commander was dead, drowned in the collapse of the wharves. The surviving captains could not come to agreement on whether they ought to pursue and punish the Rus or return to Atil and face condemnation, and possibly execution, by the bek for having disobeyed his direct order that no one interfere with or harass the Northmen in their “trading mission” among the peoples of the littoral. This order was accompanied by rumors that these same ambitious Northmen had backed the new bek in his coup; but an order it remained. Now the Arsiyah, whose most prized asset as with all mercenary elites was not their skill at arms and horsemanship or fearsome reputation but the stainless banner of their loyalty, found themselves confronted by the dawning awareness that the only thing less forgivable than a mutiny was a mutiny that failed.

“They will go south, to Derbent,” said the first captain, a florid, gaunt man bleeding from a dozen cuts, naming the next great Muslim town on the littoral. “We must anticipate them there.”

His fellow captain, stout and languid of manner, pointed out the unlikeliness of their arriving at Derbent in time or force enough to stop the Northmen, who had the advantage of a prevailing north wind, and then by way of epilogue composed on the spot an unfavorable judgment on the gaunt captain’s intelligence in even offering such a futile suggestion. The two officers were separated by their men only long enough to permit a general exchange of insults that soon devolved into a melee. In the course of the fighting, the lean captain ran onto the sword point of the stocky one and added his own life to the day’s grim total and to the slick, rank slurry of blood and dust that filmed the square.

A shrill horseman’s whistle split the air, and the soldiers abandoned the violence of their grief and turned to listen to the words of a trooper who had stayed out of the fracas, a wiry, bowlegged veteran nearly as grizzled as Amram, one of those men of no great rank or bravery who by virtue of heartlessness, opportunism and a long streak of luck outlasted all their fellows and so ranked as secret commanders of their troops. When this old veteran had the ears of his comrades, he explained, with patience and regret, and with Hanukkah keeping up a whispered translation into Arabic for the benefit of Amram and Zelikman, that they must now consider their company disbanded and, each man taking a share of water and food and a horse, scatter to the winds and the mountains, like drops of mercury on a rumpled carpet. In Hanukkah’s view there was merit in this suggestion, but it was so greatly outweighed by shame and ignominy that a number of Arsiyah, unable to refute the old veteran’s wisdom, sat down in the shadow of the mosque and cried.

The spectacle of weeping cavalrymen seemed to have a stimulating effect on Filaq. He rose to his feet, nose wrinkled as if in disgust, fists balled at his sides, and called for the men’s attention. In his thin and reedy voice, he harangued the troopers in terms that made the most hardened soldiers among them flush, while those who had been lamenting fell silent. One or two sniggered at the youth’s use of a particularly vile Bulgar epithet and smiled at each other under lowered brows.

“What does he say?” Zelikman asked Hanukkah

“He says,” Hanukkah said in a whisper, “that he has a proposition to make, but it is to be heard only by men in full possession of their manhood, and not by a mob of blubbering grandmothers who would spare the Northmen the trouble of gelding them by performing that service upon themselves.”

“What proposition?”

“I can only imagine,” Hanukkah said, “having sampled his wares in that line a week ago, sitting around the fire with my fellow gentlemen of the road.”

But now that Filaq had the attention of the soldiers, he seemed to lose his nerve or his taste for handing out abuse, and wavered, blinking and swallowing, as if the thread of his own argument eluded him. Amram glanced at Hanukkah, then rubbing his chin contemplated the soldiery, who stood in the square gazing down at their bloody buskins like farmhands awaiting the lash. In one of their Western tongues Amram put a solemn question to Zelikman. Its import appeared to consist in assessing his partner’s readiness for some hard business whose profit was outweighed by its impracticability. Zelikman’s face expressed first grave reservation and then utter lack of interest. Amram went to Filaq and took up a place just behind and to the right of him.

“Go on,” Amram told him, in passable Khazari, giving him a gentle push. “Do it.”

Filaq pushed back, the expression on his face wondering and doubtful, reluctant and eager, returned for an instant to childishness.

“It isn’t going to work,” he said.

“Probably not,” Amram agreed. “It’s a terrible idea. But it seems that nobody here has a better one.”

Filaq nodded and climbed to the top step of the mosque. He ran the back of a hand across his forehead and stood looking down at the weary soldiers, searching for the words to wake them.

“Do they know who he is?” Zelikman said. “Who his father was?”

“They will now,” Hanukkah said.

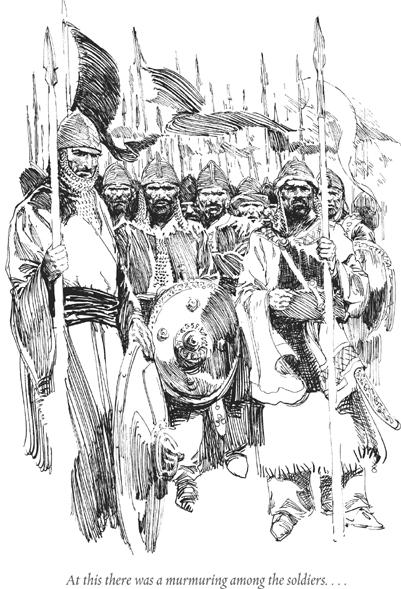

So Filaq told his story, turning fine phrases in the dialect of the palaces and gardens. He asked them first to remember the fair and temperate rule of his father, the late bek, of whom, he now revealed, he was the youngest son. At this there was a murmuring among the soldiers, and one of them said that indeed Filaq resembled very strongly the late bekun, whom the soldier had seen once during the festivities attending the Feast of Tabernacles in Atil.

Next Filaq reminded them of the kindness and consideration that his late father had always shown his Muslim subjects, and above all his faithful Arsiyah mercenaries, of whom he, Filaq, had heard it said and been ready to believe that they were the very last troops in the Army of Khazaria to swear loyalty to the usurper Buljan. The Arsiyah agreed that this could not be gainsaid, and a notion of the business the youth was about to propose began to blow among the enervated and downcast soldiers like a wind through dry rushes.

“We can be at the gates of Atil in two weeks,” Filaq said. “Along the way we will surely pass through other towns, cities of the Prophet that have known defilement by the Rus. When they see your example, your loyalty to the family of my father, that great respecter of the property and the faiths of all his peoples, they will flock to our banner. By the time we reach the capital there will be thousands sworn to the cause of restoring the true heir: Alp, my good, my wise and pious brother, that strong fighter, that wolf of our ancestors, that keeper of the law common to Jews and Muslims, whom Buljan sold to the Northmen. Thousands! Ten thousand!”

“Hundreds, at least,” the old veteran said. “Possibly even dozens.”

The wind of righteous adventure that had begun to sweep through the square subsided as this secret captain and master of the accumulated lore of soldierly skepticism began to explain that any king who controlled both the treasury and the army was, in the eyes of the world, legitimate, and that while no one could know the mind of God, the Almighty had in the past shown a marked tendency, in his view, to ratify public opinion. If the Rus had treated the towns along the coast between here and Atil as harshly as they had this poor ruin, a rebellion could hope for little to feed them along the way, let alone to swell their ranks. He had just begun to describe the torments that, he understood, awaited those convicted of mutiny when, taxed apparently by lack of food and drink and the exhaustion of the past week, his eyes rolled in their sockets, and his head tipped backward, and he slid boneless to the ground, where, fortunately for him, his skull was spared fracture by the timely action of Zelikman, who caught him and eased him to the ground, concealing the pad of wadded chamois in his fist so adroitly that Hanukkah was certain no one saw it but him.

“God has silenced this man and his cowardly counsel,” Amram said in Arabic, the mother tongue of the Arsiyah. “Perhaps you would do well to heed this indication of His will.”

There was general acclaim at this suggestion, shouts and whoops and wild ululation of the steppes, but it all ceased abruptly when Filaq pumped his fist and cried: “Alp! Alp!”