George's Grand Tour (11 page)

Read George's Grand Tour Online

Authors: Caroline Vermalle

George was relieved to see Charles in the breakfast room; he had been beginning to worry. Charles told him with a little smile that he had received the message, but had thought it might be better to give them some time alone. George returned his smile. No need to go into detail.

But the words that George had been going through in his head all night weren't coming out. What was more, he didn't want Charles to think that it was because of the ridiculous squabble by the Louison Bobet. He had to play this very carefully.

âErm, Charles, I've got something to tell you. I think I might stop here, you know.'

âI see,' said Charles, suddenly sitting very straight in his seat.

âYes. It's all very well going on an adventure, but it's hard on my old bones. I feel like such an old fool, and I'm sorry to have

to let you down like this but sometimes you just have to listen to yourself and I can't keep going if my heart's not in it. Well, I say that; it's actually the rest of my body that needs a break. I've been thinking about it for the last few stages. I can't keep up any more.'

Charles said nothing.

âAnd I'll tell you something else, Charles. I didn't see any of Brocéliande Forest. Instead, I had a two-hour snooze in a supermarket car park in Saint-Méen. And it wasn't even a good nap, because we were cross with one another.'

âFunny you should say that,' Charles replied sadly. âI didn't see any of the museum either; it was shut. So I had a little kip too, in the Café des Sports in Saint-Méen. And you're right, it's hard to sleep when you've ⦠Well, you know what I mean.'

Charles looked more emotional than George had imagined, which threw him off guard. Almost in a whisper, Charles murmured:

âIt's Ginette, isn't it?'

âNot just her ⦠I mean, she is partly why,' George answered after a moment's hesitation. âShe's invited me to stay in Notre-Dame-de-Monts. To spend the week there. It'd be a good chance to recover after so many days on the road. And bloody good days they were too, by the way. That's why I think there's no shame in taking a little break.'

As if he hadn't heard any of this explanation, Charles looked at him with tears in his eyes, and asked in a quiet voice:

âIsn't there any way you could spend a week there after the last stage? Or we could even go before, if we could just go a little way further?'

It was the first time that George had seen Charles's vulnerable side, good old Charles with his rough farmers' hands, and it upset him a great deal. He felt as though Charles was hiding something from him. For the first time in years, he couldn't read his neighbour, and he was momentarily lost for words.

âCharles, it's not as if we're after the yellow jersey, right?'

The words he had repeated to himself over and over in his head now rang false.

Charles stared wordlessly down at his breakfast. After a long silence, he said:

âGinette doesn't know what's going on. If she did, she'd never have invited you to stay with her.'

George was taken aback.

âW-what do you mean?' he stuttered. âI've never kept anything from Ginette, I've never kept anything from anyone, I'mâ'

âWhat I mean is, she doesn't know why I'm doing this.'

âOh, Charles, you're doing it because it was your boyhood dream and we're all allowed to try and realise our boyhood dreams at the grand old age of eighty, there's no shame in that, none at all! And we've been gallivanting around like a couple of young boys for the last two weeks, but I'm sorry to say that my legs can't take any more and I wouldn't say no to a little break ⦠And who knows, maybe we'll even finish it some day.'

âNo George,' Charles interrupted. âThat's not why I'm here. Of course I've been dreaming of this for yonks but whether it was this or something else, it's not a lack of anything else to do that's the problem. I'm doing it because I need â¦'

He paused for a moment, and then continued:

âI need you and this Tour and to get out and see the world

because my mind is getting worse by the day, George. It's the curse of old age; my brain is

degenerating

and it doesn't matter how many times they tell you that that's just the way it is, and there's no avoiding it, believe me George, when it does hit you it's a living nightmare. And there's no medication for it, there's nothing but the loony bin and big black holes in your memory. So the only thing the doctors tell you is that you've got to keep your noggin working at all costs. And how? They tell you to do crosswords, that's what they tell old fogeys like us, because they think that's all we're good for. But I'm telling you, you need crosswords and wordsearches and anagrams and Sudokus and all the rest of it just to keep your head straight; you need more puzzles than

Téléstar

can print. And I've had it up to here with crosswords, I can't stand them any more. I know all there is to know, all the “ing”s and the “ed”s, the abbreviations of every country; I could do crosswords for France. OK, then there's

belote

, and gardening, and letter-writing, and Scrabble â if you listened to them you'd be doing bloody basket weaving before long. But I've had enough of all that, George, I can't do it any more ⦠There's something eating away at my brain, and it's destroying everything: my memories, familiar faces, even the rooms in my home and the names of my grandkids. I've forgotten all the things I know. All of my memories have a chunk missing from them, and sometimes I get terrified that one day everything will just go, bam, and then what will be left of me? I'll be all hollowed out like a shell on the beach, with nothing left, nothing â because what's the point of being old if you don't have any memories? Is life worth living when you've got no one left, because you've forgotten who your family are?

It's worth bugger all, George. Bugger all. There you go. The only thing Thérèse and I could come up with was this Tour de France. Changing scenery every day, seeing new things, meeting new people, learning ⦠And at the same time I got to do what I'd always wanted, so when it was a choice between that and crosswords ⦠We didn't really believe it at the start, because you weren't sure, so I didn't let myself get too involved. But now, now we're doing it. Maybe it won't make a difference, maybe the lights are going to go out anyway and there's nothing I can do about it. But maybe not, maybe it'll work. Thérèse believes in it. As for me, I'm not convinced yet, but what can I do? Even if it doesn't help, it's definitely not doing any harm. And you know what, maybe I do believe in it, even if it's just because I've got to believe in something. There you go. And Ginette doesn't know. She doesn't know that her brother's losing his marbles. If she did, she wouldn't have invited you to Notre-Dame-de-Monts.'

Charles stopped talking. George didn't know what to say. He felt a lump in his throat. Why hadn't he seen this earlier? He should have worked it out from the incident with the petrol pump, and from the leftovers after the picnic at Châteauneuf-du-Faou ⦠And there had been other signs, now that he thought about it, like the day he forgot how to make a cup of tea. He now understood why Charles, who was normally unbeatable when it came to trivia, hadn't joined in the recounting of the Tour's historic moments.

What was he supposed to say? That the Tour was all very well, but what about when it was over? Was he going to go on a tour of the world? These days nothing was as far away as it had once been, it probably wouldn't even take him that long â¦

Was he planning on roaming the globe like a nomad until the end of his days, separating himself from his loved ones so he wouldn't forget them? Charles was right, there was a lot of talk of dementia and so on, but he didn't really know anything about it. It was something that happened to other people. And now he saw one of his friends clinging to illusions, trying to fight it. This Tour de France now seemed utterly absurd. At that moment he wished more than anything that he were one of life's optimists, he wished he could believe what his friend was telling him, believe that this was making him better, heck, he wished at that moment that he believed in God, because God was capable of miracles.

Charles broke the silence.

âI've got to tell you, George, I feel better for telling you. Keeping it a secret this whole time was ⦠Well, anyway I told you because you should know Ginette asked you without knowing all of this. But I guess if your joints are playing up, there's nothing we can do. Nothing we can do.'

It was a while before George had the courage to reply.

âYes, there is.'

That same afternoon, they were heading towards stage five. And this time they were determined to see it through.

Â

âAnd the Tour de France is off again! Over to you, Jean-Paul Brouchon, our man on the starting line!' said George exuberantly as he plugged in his seatbelt. The companions got back on the road with an enthusiasm neither of them had felt since the first day of the Tour â and even on that day there had been a lot less laughter. Charles's revelation had marked a new phase of their friendship. They could now say without hesitation that they

were no longer

neighbours

, they were

friends

. Charles was visibly relieved to have shared his anxiety with George. He had also had a long telephone conversation with his sister. It had come as a shock to her, but she wholeheartedly agreed that some mental exercise was just what he needed. And George would not go to see her in Notre-Dame-de-Monts for the moment, but it was agreed he would come in November.

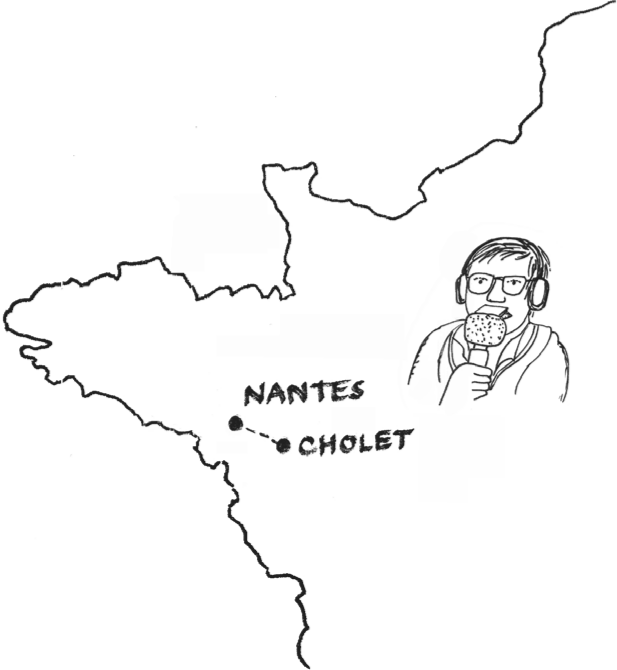

George was feeling so cheerful on the road from Nantes to Cholet that he started whistling

Y'a d'la joie

, the famous Charles Trenet song that reminded him of his childhood. Charles joined in, admittedly a little out of tune, but the end result was marvellous. And then all of a sudden, the words came pouring out of Charles's mouth: â

Miracle sans nom à la station Javel/ On voit le métro qui sort de son tunnel/ Grisé de soleil de chansons et de fleurs/ Il court vers le bois, il court à toute vapeur/ Y'a d'la joie bonjour bonjour les hirondelles!'

He sang the song all the way through. The lyrics surged up from the distant past and seemed to fill him with a fresh burst of energy. Just before the last verse, Charles was hit in his excitement by a wave of false modesty and said:

âOh, I don't think I can remember the rest.'

âEven so, I'm impressed!' said George. â“You did what you could, but you blew me away!”'

Charles thought for a few moments and then cried out:

âBrambilla! Pierre Brambilla! That's what he said to Jean Robic when he won the Tour in '47!'

âCorrect!'

âSo I haven't forgotten everything, then! Still got something between the ears!'

Slowly but surely, the Tour route was leading them back to their native region. They spent the night in Cholet with friends of Charles. After a challenging day Charles was able to relax with his friends, while George got an early night, claiming various aches and pains. In truth he was behind in his correspondence with Adèle; he caught up that evening with six texts updating her on the events of the last few days, from his day out in Nantes to the conversation with Charles. He mentioned Ginette, of course, without saying too much, but he knew Adèle would be able to read between the lines. And while he was about it, he sent a text to Ginette. Neither woman replied instantly and so, just this once, he switched off his phone, put in his earplugs and fell into a deep, untroubled sleep.

They took great joy in driving down the roads that passed through Bressuire, Mauléon, Les Herbiers and Thouars. These were the roads they had driven down all their lives; the names sounded familiar and comforting. They fitted in here. They knew what kind of bread they would find in the bakeries, they could name all the plants, trees, and even the weeds. They knew which newspapers would be on sale in the newsagents and saw familiar old men waiting to cross the road. They would doubtless recognise the names on the village war memorials, names of families who still lived nearby. George and Charles saw their little corner of the world with new eyes. They had been looking at the same things all their lives, but only now were they really paying attention.

They were so close to home that Charles and Thérèse had

arranged to meet. God knows how they managed to arrange it, thought George to himself, because Charles didn't have a mobile phone. Returning the favour that Charles had done him, George decided to give the couple some time alone and went to sit in a café in the centre of Thouars with a seven-euro menu. There were a few other pensioners sitting inside. With the customary cloth over his shoulder, the owner was talking to a local sitting at the bar. It was technically forbidden to smoke inside so he kept going back and forth to the entrance, filling the room with smoke as he went.

George instinctively reached for his phone to give him something to play with and pass the time. He had received several texts from Adèle and one from Ginette. Two little old men nursing Duralex tumblers called over to him:

âSo young man, you're playing at mobile phones just like the kids, eh?'

âWell, I've got to,' George answered politely. âFor the granddaughter, you know how it is.'

And he turned his attention back to his text message, but the two men were clearly in a playful mood:

âNo, I dunno how it is, and I dun' want to know. If we're meant to do everything the kids do these days just to bloody talk to 'em, I dunno ⦠young people these days can't go a 'undred metres without tap-tap-tapping at their phones.'

And he imitated someone frantically writing a text. Before George had time to think to himself that this speech sounded familiar, the owner's wife rescued him by murmuring confidentially:

âWould you like to sit in the dining room upstairs? It's a little calmer up there.'

The dining room was pretty, with walls lined with tapestries. The owner's wife cleared the table and her iron, which she had left by the window, and gave him cutlery and a napkin.

Finally, he could concentrate on his texts. Ginette's was mainly about the weather. Adèle was unhappy with her working hours. Ginette had been to visit a friend in Les Sables-d'Olonne. Adèle was worried she was coming down with a cold. Ginette had decided to redecorate the kitchen before November. Adèle had recovered from the cold, thanks for asking. Nothing especially interesting, in short. Nothing urgent. How funny that it had taken him eighty-three years to see the enjoyment in small talk.

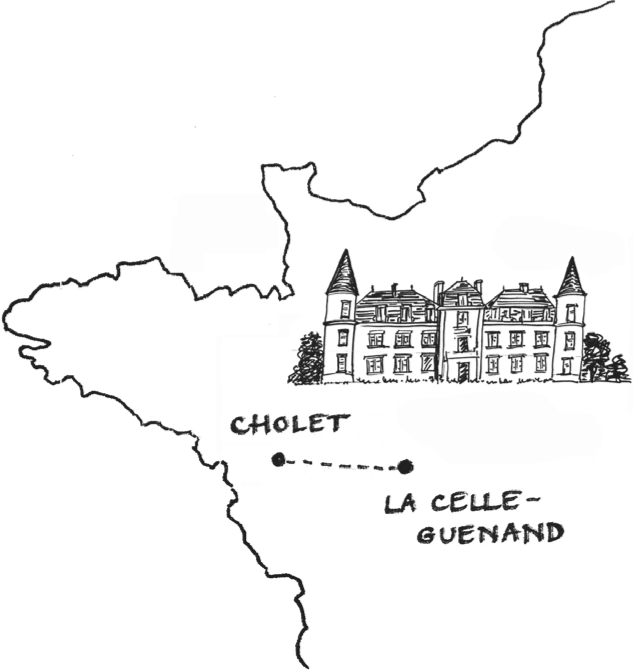

A little later, Charles came to meet George, told him Thérèse sent her love, and off they went again. They drove on to Le Grand-Pressigny, which had witnessed the Tour, and La Celle-Guenand, which had not but it did have a magnificent seventeenth-century château where they could stay for forty-five euros a night. Charles and George were struck by the vivid autumnal shades of the Touraine landscape, the pastel grey and orange of the fields, the slate roofs and delicate clouds that drifted across the sky like puffs of smoke, the lush green forests and the dried sunflowers that seemed to bow their brown heads in repentance. Any doubts George had felt about continuing the Tour had now vanished.

Â

For as long as they could remember, there had been a tacit understanding that George was wealthier than Charles. And

although this was a simple fact for George, Charles had never quite felt comfortable about the situation. So he was particularly proud to be taking George out for dinner that evening, in Le Petit-Pressigny. Not to just any restaurant either; this one was mentioned in all of the guidebooks, and had even been awarded the much-coveted Michelin star, with particular praise for its speciality: rustic bacon wrapped in buttered green cabbage, with black pudding and crackling. This was not Charles trying to show off to George, of course; rather the two companions had not had a chance to celebrate their epic undertaking properly, apart from the half-hearted Kir in Guémené. And so it was with genuine delight that George accepted the generous invitation. It was an evening to remember; the exquisite food and wine enhanced the euphoria of recent events. The pair were the last, and happiest, people in the restaurant. Neither of them wanted the day to end.