Georgian London: Into the Streets (25 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

Not content with building a serious London-based business, Lamerie expanded into the export trade. Robert Dingley was a goldsmith on Cornhill who had connections to the Russian court. He took orders for certain items and had them made by Huguenot craftsmen, but he wasn’t in the habit of paying the tax on them before they were exported. In August 1726, officials tried to seize the cargo as it lay aboard ship near Customs House. Dingley, who had been tipped off, was waiting for the officials and took them to the Vine Tavern in Thames Street, just around the corner from the ship’s mooring, to discuss the matter. As soon as they were inside the inn, the ship slipped its mooring and sailed for Russia. Dingley was brought before Guildhall Court, where he testified that the 18,000 ounces of the Tsarina’s purchases had all been properly hallmarked. The vast majority of the Tsarina’s collection, now in the Hermitage, is not hallmarked. More than half of it bears only the maker’s mark of Paul de Lamerie.

However, in December 1737, the poacher turned gamekeeper when Paul de Lamerie was appointed to a Parliamentary Committee to prevent fraud in gold and silver work. The committee intended to restore the Goldsmiths’ Company’s medieval right to search the premises of goldsmiths. This was the year Paul de Lamerie sold a large duty-dodging ewer to Lord Hardwicke. Unsurprisingly, he insisted the clause be ‘entirely left out of the new intended bill’ and then failed to turn up for the subsequent meetings.

He died in 1751, from a ‘long and tedious illness’, and was interred in St Anne’s Church, Soho.

The General Advertiser

reported that: ‘His

corpse was followed to the grave by real Mourners, for he was a good man, and his Behaviour in and out of Business gain’d him Friends.’ His tomb was destroyed in 1939, when the church suffered significant damage during an air raid.

It would be easy to cast Paul de Lamerie in the mould of villain: cheating the system, swindling a chimney sweep and lying to anyone in authority. Yet a document pertaining to the French Hospital for Huguenots ties Paul de Lamerie to an act of decency, and one typical of the close-knit French community in Georgian London. James Ray was a gilder. The heated mercury used in the gilding process often sent workers mad and, in 1734, Ray began ‘running about the streets like a madman, forsaking his business and crying “oranges and lemons”’. Before admitting a violently ‘distracted soul’ to any hospital, it was customary to find a member of the community who would pay for damage caused by the patient. The signature on James Ray’s bond is that of Paul de Lamerie.

Close to the French parish of St Anne’s was St Martin’s Lane, full of creative types and pioneers.

Here, treatises on fireworks

and the first English pamphlet on figure-skating were written by Robert Jones, who would later be condemned to death for abusing a twelve-year-old boy in his lodgings. Many engravers, painters and intellectuals lived on or close to the street, and they all congregated in Old Slaughter’s Coffee House.

Over the years, Old Slaughter’s played host to William Hogarth, William Kent, the engraver Hubert Gravelot, the sculptors Henry Cheere and François Roubiliac, the writer Henry Fielding, the artists Francis Hayman, Thomas Gainsborough and George Moser, and the Huguenot mathematician Abraham de Moivre. When money was tight, de Moivre gave maths lessons here. Isaac Newton lived nearby, and the two were friendly. Theirs was far from a serious society, yet the coffee house was not a frivolous place of entertainment. The

inhabitants of these quasi-public spaces were not only thinkers, writers and artists but also ordinary men. ‘

All Englishmen are great newsmongers,’ the visitor César de Saussure was to remark. In 1730, he wrote that they ‘habitually begin the day by going to the coffee rooms to read the latest news

’. Just as City coffee houses catered for remarkable and specialist cabals in stocks, banking and insurance, Old Slaughter’s catered for a band of artists known as the St Martin’s Lane Group.

The art group was organized by William Hogarth, who set up a life-drawing class in Peter’s Court, just off the lane. Hogarth’s sign was Anthony van Dyck’s head: from ‘

a mass of cork

made up of several thicknesses compacted together, [he] carved a bust of Vandyck, which he gilt, and placed over his door’. It harked back to a golden age of British ‘courtly’ art, when van Dyck was court painter to Charles I, the greatest royal patron.

The following year, a young Yorkshireman rented three houses in St Martin’s Lane. The move was a departure from everything he knew, a monumental risk for a man of thirty-six with a rapidly expanding family. The young man was Thomas Chippendale.

His St Martin’s Lane premises were not so much a workshop as an expression of his desire to change the way the English occupied their drawing rooms. In 1753, Hogarth published his ideas on art in

An Analysis of Beauty

. In 1754, Chippendale published his

Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director

and changed the way English furniture was bought and made.

What Chippendale did was not particularly new; others, such as Batty Langley, had been producing books of designs for gardens and buildings since the early eighteenth century. What Chippendale did was to imagine a harmonious interior, much in the way that Hogarth thought about the composition of a picture. His designs were fashionable, and available. Soon, he had a large group of men and apprentices working from what became 61 St Martin’s Lane while he and his wife lived next door.

Chippendale changed the way his contemporaries thought about design and furniture, and he continues to define a style and type. He did not sign his furniture, so only pieces accompanied by an

invoice from Thomas Chippendale can be connected to him. Chippendale’s success was to do with the coherent, distinctive themes of his manual. Anyone with reasonable skill could buy the book and create ‘Chippendale’ furniture in the latest fashion, in whatever wood was available. Examples are seen in oak, elm, walnut and mahogany. The

Director

was so successful that there is nothing to tell between pieces made by Chippendale and his more talented imitators.

The artistic environment in Soho was pervasive. In 1746, William Hunter the anatomist arrived in Paul de Lamerie’s Windmill Street and set up his Anatomy School so that ‘

Gentlemen may have

an opportunity of learning the Art of Dissecting during the whole winter season, in the same manners as at Paris’.

Hunter was already making large strides into the science of obstetrics. This included making casts of women and their reproductive organs when they had died in various stages of pregnancy. These casts in plaster were then painted to resemble the living form and used for teaching purposes.

Knowledge of the human body was essential for artists, and had been a vital part of artistic education since Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. In the early 1750s, the artists of the St Martin’s Lane Academy engaged William Hunter to help them develop their understanding of the human body, how it worked and moved. This combination created one of the most important artistic experiments in the eighteenth century.

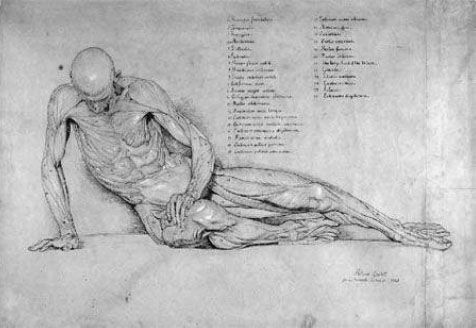

‘Écorché’ means flayed, and by removing the skin and fat of a corpse William Hunter was able to explain the underlying musculature to his pupils, who by now had their own corpse to practise upon. Realizing this musculature would be equally valuable to art students, Hunter set about creating a series of écorché casts. The first, a man with his right arm raised and his left slightly out from his body, was

chosen by Hunter and the St Martin’s Lane group from criminals executed at Tyburn. The body of a murderer was chosen because of the beauty of his physique. He was transported to St Martin’s Lane before rigor mortis had set in, then Hunter and the artists placed him into ‘

an attitude’. When ‘he became stif we all set to work and by the next morning we had the external muscles all well exposed ready for making a mold from him

’.

The resulting écorché figure is now part of the collection of the Royal Academy, who appreciate life models who can keep very still. In his opening address as President of the Royal Academy on 2 January 1769, Joshua Reynolds posited his theory that life drawing was essential to the skills of an artist, stating: ‘

He who endeavours

to copy nicely the figure before him, not only acquires a habit of exactness and precision, but is continually advancing in his knowledge of the human figure.’ In the same year, William Hunter was appointed Professor of Anatomy at the Royal Academy. In the late 1760s, as Hunter became more closely allied to the artists who would become the Royal Academicians, he associated art with medicine ever more closely, resulting in the work for which he is still remembered:

The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures

(published in 1774). This beautifully illustrated book, with its engravings by Jan van Rymsdyk, did much to advance the understanding of the mechanics of pregnancy.

In 1775, the most famous of the Royal Academy’s écorché figures arrived. William Hunter arranged with the sculptor Augustino Carlini that they would obtain a corpse from Tyburn. The identity of the dead man remains controversial, as Hunter chose the best physical specimen on the day. It could be one of two men: Thomas Henman or Benjamin Harley. The body was taken back to Windmill Street and flayed, which took most of the night. When the work was done, he was placed in the position of the Dying Gaul, allowing the head to fall forwards on its broken neck. The original bronze used in the Royal Academy rooms has now been lost but another cast survives in the Edinburgh College of Art. He became known as ‘Smugglerius’, supposedly after the crime for which he was executed.

‘The Dying Gaul, or Smugglerius’, the flayed body of a Tyburn corpse, drawing by William Linnell, 1840

In 1801, Richard Cosway, by then President of the Royal Academy, was keen to do another anatomical figure, that of Christ Crucified. The body of murderer James Legg was taken back to Windmill Street and flayed whilst still malleable. He was crucified, and they watched as he ‘

fell into the position

a dead body must naturally fall into’. He was then cast.

The Royal Academy also used skeletons and life models, and these became increasingly important as public taste turned against using the écorché criminals. ‘

These kind of figures

,’ a critic stated, in 1785, ‘do very well for the Academy in private, but they are by no means calculated for the Academy in public.’ Increasingly, models were chosen from the streets, often being men of extraordinary natural musculature or cases where the body had become superannuated through physical labour, such as coal-heaving.

One life model, Wilson, arrived in London in the summer of 1810. He was ‘

a black, a native

of Boston, a perfect antique figure alive’. On the journey, or soon after disembarking from the ship, he was injured and visited Dr Anthony Carlisle. Carlisle was one of

William Hunter’s successors as Professor of Anatomy at the Royal Academy. He immediately saw his patient’s potential, and hauled him into life classes.

Thomas Lawrence was particularly impressed

, and declared Wilson ‘the finest figure … [he had] ever seen, combining the character & perfection of many of the Antique statues’.

Benjamin Robert Haydon, Wilson’s regular employer, soon took him on for extended periods of time to make the detailed sketches which would inform an entire career. Haydon’s admiration bordered on the fervent. Years later, he would wistfully remember how, ‘pushed to enthusiasm by the beauty of this man’s form, I cast him, drew him and painted him till I had mastered every part.’ He cast Wilson’s whole body, up to his neck in seven bushels of plaster, but noted: ‘In moulding from nature great care is required … by the time you come to his chest he labours to breathe greatly.’ Wilson passed out inside the casing of hot plaster, and Haydon and his workmen broke him out ‘almost gone’. At first, they were busy attending to Wilson, who ‘lay on the ground senseless and streaming with perspiration’, but when he began to recover Haydon looked at the mould of Wilson’s buttocks ‘which had not been injured’. He described them as ‘the most beautiful sight on earth’ before remarking, ‘the Negro, it may be said, was very nearly killed in the process, but in a day or two recovered.’ Indeed, Wilson came back to Haydon after ‘having been up all night, quite tipsy’ and wanted to make another cast.

Wilson’s fleeting cameo in London is too short, and much of what it reveals does not reflect favourably upon the attitudes of artists or critics; he was at once beautiful, yet parts of his face and body corresponded to ‘the animal’. In every modern sense, Wilson was an American man who came to London and made a small fortune in a short time. For him, London’s streets really were paved with gold. The image his body created – that of the noble savage – would endure to become an icon for abolitionists. For most of the nineteenth century, his body-type dominated the image of the black male in British and American art. The details of Wilson’s life may be sparse, but we are left with the image of an ‘extraordinary fine figure’.