Getting Into Character: Seven Secrets a Novelist Can Learn From Actors (9 page)

Read Getting Into Character: Seven Secrets a Novelist Can Learn From Actors Online

Authors: Brandilyn Collins

Tags: #Writing

With this opening, Steinbeck begins to build Kino’s Desire. Kino wants to gain wealth in order to raise his family out of poverty. We see how hurt and upset he is over not being able to provide the medical care his baby needs. More than anything he wants a better life for his son.

Kino is well set up for the inciting incident to occur, which will change and specify his Desire. The inciting incident: As Kino dives he does indeed find a huge pearl—the “greatest pearl in the world.” In this case the inciting incident—at least at this point in the story—appears positive instead of negative. Kino’s Desire is now completed: “I want to sell this pearl for its full value so that I can raise my family out of poverty.”

Note that this Desire has three parts. The first two are in the first prong: (1) “I want to sell this pearl” (2) “for its full value.” The second prong is the ultimate goal of caring well for his family, especially his son.

Looking at the various parts of this Desire, can you already think of some potential scenes for conflict?

We’ll come back to this example in our discussion of the second D.

One final note about Desire

As we’ve discussed, knowing your character’s Desire helps you plot your novel. One immediate way it helps is to lead you to the story’s conclusion. When readers see what your character is pursuing, an inevitable question is placed in their minds: Will the protagonist obtain that Desire? The resolving of this question is your novel’s “answering end.” Your character will obtain his Desire or he won’t. Maybe he obtains only part of it. Or he may obtain the whole Desire, but at far greater cost than he ever wanted to pay. Or he may have the Desire within his grasp but decide he doesn’t want it after all, like Scarlett O’Hara. The possibilities are many.

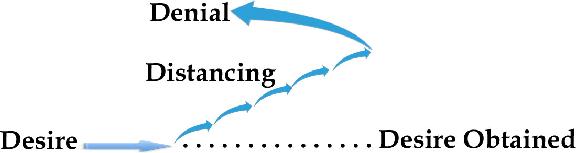

Once you determine your character’s Desire and the answering end of your story, you have a picture of your character’s starting and finishing points. If you were to diagram your story at this point, with your character obtaining his Desire, it might look like this:

If the character does not obtain his Desire, the diagram might look like this:

Okay, I can hear the pantsers screaming now. “I’m not a plotter!” Fine. But usually even the strongest pantsers know something about their story when they begin. If you know the inciting incident—which forms the premise of your book—and you know whether or not your character will obtain her Desire, a lot of unknowns remain in the middle. There’s still plenty of room to do your pantser thing. If you don’t want to know how the story turns out—whether your protagonist obtains his Desire or not—fine. Just don’t fill in the “answering end” question. But

do

start your novel with a strong knowledge of who your character is, his inner values, and his Desire. With these guides in mind, you can progress with your story in a logical way. And you’ll follow fewer rabbit trails—scenes that will eventually need to be discarded.

The Second D: Distancing

The trouble with the first diagram above is that it represents a very boring novel. There’s no satisfying story in a character’s desiring something and homing in on a straight, unobstructed course to obtain it. Story is about conflict. Story occurs when a character meets opposition along the course of pursuing his Desire and then struggles to overcome it. The second D—Distancing—refers to the conflicts that arise as barriers to oppose your character as he pursues his Desire. These will form the main body of your novel. If you experience a “sagging middle” it’s during this Distancing process. Go back and take another look at your protagonist’s Desire. Is it strong enough to propel him through the story? Is it specific enough?

As these conflicts build upon one another, they push or “distance” your character farther and farther off his path. This Distancing increases until your character reaches the third D.

Picture again the analogy of the straight brick path, created to most efficiently link the beginning and end points. If you were following that path, and a large wall suddenly loomed in your way, what would you do? You’d go around it with the intention of getting back on the path as soon as possible. But say you go around the wall and discover a huge tree in your way. Now you have to go around the tree, which leaves you even farther from the path. And once you’re around the tree, there’s a building in front of you. So you go around the building, leaving you even

farther

from the path. Still your intent is to get back on the path as quickly as you can.

This is human nature. We don’t like conflicts that come out of nowhere and knock us from the path we choose to follow. The stronger our desire to reach the end of the path, the harder we’ll fight to return to it. In addition, it’s human nature to believe we will succeed in getting around that first conflict, and then we’ll have a straight path once again. At the first sign of problems we don’t tend to visualize a series of conflicts that will knock us farther and farther off course. We should, because that’s often what life does. But we tend to be optimistic creatures.

Think of someone who is told he has cancer, with only six months to live. That person will not immediately say, “Okay, I accept that. I’ll never finish the path of life I was on.” Quite the contrary. The first reaction is to fight it. To say, “No matter what the doctors tell me, no matter how little chance I have,

I

will beat this illness.” The person envisions himself going around the wall of cancer and getting back on his path.

In the same way your protagonist is on his path of life. He has goals he wants to achieve in his normal world. Then an unexpected event occurs—the inciting incident—that knocks him off that path. At this point his Desire is formed. He will spend the rest of the book dealing with that incident and subsequent conflicts, always with the intent to get back on the path that leads to obtainment of his Desire.

Example of Distancing

Let’s look again to

Steinbeck’s

The Pearl

. When Kino finds the “greatest pearl in the world,” his Desire is formed: “I want to sell this pearl for its full value so that I can raise my family out of poverty.”

Remember our discussion about how specific Kino’s Desire is. He doesn’t want to just sell the pearl for some fast money. He wants to sell it at its full value. And the goal of selling the pearl is to raise his family from poverty. Kino dreams of providing his son with the kind of life Kino himself had never enjoyed. When Steinbeck created Kino with this specific Desire, he set the character on an inevitable course he will doggedly pursue even as one conflict after another arises.

Kino finds himself in danger because others want to steal the pearl. In trying to protect the pearl he loses his house and fishing boat. Now he

really

has to sell the pearl, because they’ve lost what little they had. He can’t even make a menial living without his boat. But his wife begins to tell Kino they should throw the pearl back into the sea. It’s bringing them nothing but evil. Kino cannot listen. He remains obsessed with selling the pearl.

Next, he finds that he can sell the pearl, but for far less than its real value, for would-be buyers want to cheat him. (See how this specific part of his Desire leads to further conflict?) So he must set out on a journey with his wife and child to the capital, where he can find a proper buyer. But the journey will place not only himself but also his wife and child in danger from those who would steal the pearl.

Making that journey is the kind of choice that, at the beginning of the story, Kino would never have even considered. His end goal is to give his son a better life. Now he’s putting that same son in danger? Why does he do this? Why doesn’t Kino listen to his wife when she continues to say the pearl is bringing evil? Because of his very specific, very strong two-pronged Desire, which propels him through Steinbeck’s tragic story. The fact that the second prong of Kino’s Desire focuses on bettering his family sets up the book’s irony. His very obsession to richly provide for them by selling the pearl for its full value leads him to make poor choices he otherwise would never have made. By this point in the story readers can see the foolishness of Kino’s choices, even though he, driven by his Desire, cannot. At the same time, his poor choices are believable. Why? Because Steinbeck took the time at the beginning of the story to set Kino’s Desire so strongly in place that all he can think of, despite conflict after worsening conflict, is to get back on his path of providing a better life for his son. And to do that he has to sell the pearl. Readers can understand Kino’s motivation. They may not agree with what he does, but they understand why he does it. It’s part of the human condition. Sometimes we’re so blinded by what we want, we can’t see that our desire is ruining us.

Also—remember my earlier point regarding how the second prong, if focused on a good cause, can keep your character from seeming selfish and shallow? That’s at play here. Imagine if the second prong was all about Kino. If he was single—no wife, no child—and all he wanted was wealth for himself. Or worse, if he had a family, but wanted the money for his own gain, not theirs. We wouldn’t like him. Nor would we understand his poor choices. We’d just think he was an idiot, deserving everything he gets. But a Desire that involves the well-being of a loved one, especially a child, is a different matter.

The Third D: Denial

The third D is the Denial of your character’s Desire. The Distancing conflicts have built up to such a degree that all now appears hopeless. Tension and suspense are at their peak. No matter how hard your character has tried, how much he has hoped, he now faces the worst conflict of all, which brings a terrible realization—he just might not attain his Desire at all.

The Denial occurs at the time of your story often called the “crisis.” It is nearing the end of your novel. Usually it takes place in one pivotal scene. Sometimes a quick sequence of scenes forms the Denial.