Ghostwriting

- Introduction

- The Man Who Never Read Novels

- Beauregard

- Li Ketsuwan

- Ghostwriting

- Taipusan

- The Memory of Joy

- The Disciples of Apollo

- The House

Ghostwriting

Eric Brown

infinity plus

Ghostwriting

Over the course of a career spanning twenty five years, Eric Brown has written just a handful of horror and ghost stories – and all of them are collected here. They range from the gentle, psychological chiller "The House" to the more overtly fantastical horror of "Li Ketsuwan", from the contemporary science fiction of "The Memory of Joy" to the almost-mainstream of "The Man Who Never Read Novels". What they have in common is a concern for character and gripping story-telling.

Ghostwriting

is Eric Brown at his humane and compelling best.

Published by infinity plus at Smashwords

www.infinityplus.co.uk/books

Follow @ipebooks on Twitter

© Eric Brown 2012

ISBN: 9781476285429

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

The moral right of Eric Brown to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

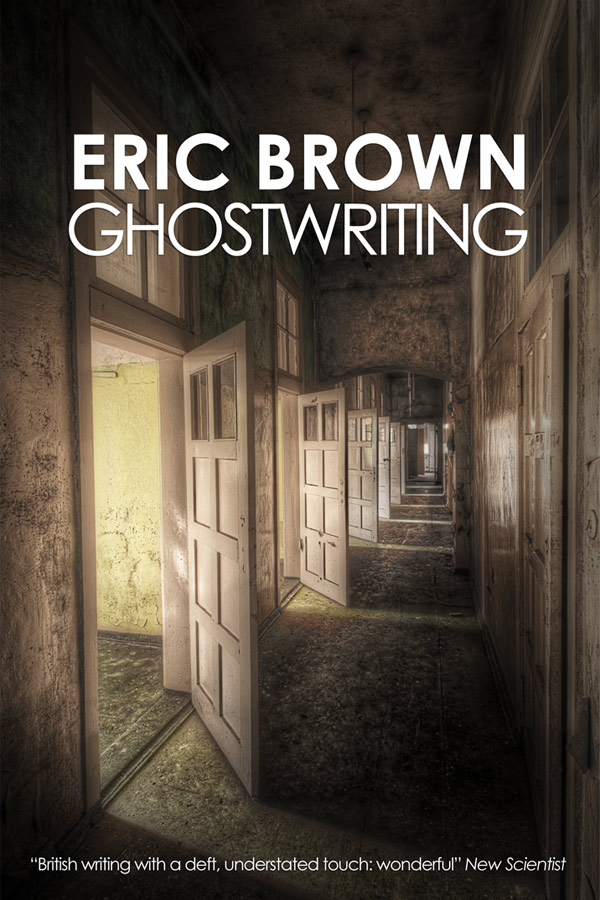

Cover image: © Unkreatives | Dreamstime.com

Electronic version by Baen Books

Acknowledgements

“The Man Who Never Read Novels” first published in

Cemetery Dance

#54, 2005.

“Beauregard” first published in

Dark Terrors 5

, 2000.

“Li Ketsuwan” first published in

The Third Alternative

34, 2003.

“Ghostwriting” first published in

Cemetery Dance

#59, 2008.

“Taipusan” first published in

Cemetery Dance

#60, 2009.

“The Memory of Joy” first published in

Choices

, 2006.

“The Disciples of Apollo” first published in

Other Edens 3

, 1989.

“The House” first published in

House of Fear

, Solaris, 2011.

~

I’d like to take this opportunity to thank the editors who first published these stories: Robert Morrish, Stephen Jones, David Sutton, Andy Cox, Christopher Teague, Christopher Evans, Robert Holdstock, and Jonathan Oliver.

Also by Eric Brown

Novels

The Kings of Eternity

Guardians of the Phoenix

Cosmopath

Xenopath

Necropath

Kéthani

Helix

New York Dreams

New York Blues

New York Nights

Penumbra

Engineman

Meridian Days

Novellas

Starship Winter

Gilbert and Edgar on Mars

Starship Fall

Revenge

Starship Summer

The Extraordinary Voyage of Jules Verne

Approaching Omega

A Writer’s Life

Collections

The Angels of Life and Death

Threshold Shift

The Fall of Tartarus

Deep Future

Parallax View

(with Keith Brooke)

Blue Shifting

The Time-Lapsed Man

As Editor

The Mammoth Book of New Jules Verne Adventures

(with Mike Ashley)

Introduction

I write very few short stories that can be termed horror, ghost, supernatural, occult, or fantasy. In fact, in a career spanning twenty-five years I’ve written just eight (nine, if you include the novella

A Writer’s Life

) out of a total of around a hundred and twenty published stories. Most of those have been science fiction, a genre with which I feel more comfortable. The ideas I have just happen to be about the future, concerning the staple tropes of the genre: other worlds, space-flight, aliens, fantastical technologies, time-travel... I rarely get ideas that fit neatly into the horror genre or related sub-genres.

Now, why is this?

Perhaps it’s because my preferred reading, along with mainstream novels, is SF. I’ve been reading it since I was about fifteen and I know it inside out. I do occasionally read horror (or ghost or supernatural), and enjoy the likes of Robert Aickman, R. Chetwynd-Hayes, M.R. James, and more modern practitioners like Joe Hill, T.E.D. Klein, Adam Neville. And while I can appreciate the literary merits of the genre, I always have to work hard at suspending my disbelief. Fundamentally, I don’t believe in the occult, ghosts, ghouls, vampires, etc... Therefore when I come to write about them, I find it that much more difficult to do so.

Now I can hear you crying, “Why! That’s ridiculous! What makes ghosts, ghouls, vampires etc any less credible than little blue aliens, FTL travel and all the other fantastical trappings of SF?” And I admit that there is, perhaps, nothing more credible about the furniture of SF... other than a sneaking suspicion I have that the things I write about in SF might, just might, possibly, in some way, at some point in the future, come to pass. At any rate, the characters I write about in my science fiction tales believe implicitly in the scientific process and believe that the fantastical things in their world have a credible, rational, scientific basis.

When I do get ideas for horror tales, I find that they’re about the exploration of character. They’re gentle horror tales, often metaphorical, with little or no blood and guts, precious few ghosts, ghouls, and certainly no werewolves or vampires. I prefer to call them psychological horror stories.

Which brings me to the eight short tales of ‘horror’, for want of a better term, collected in this volume.

A few years ago the then editor of the horror magazine

Cemetery Dance

, Robert Morrish, contacted me saying that he’d very much enjoyed

A Writer’s Life

, and that if I wrote any further horror stories could he take a look at them. Never one to turn down an opportunity, I wrote “The Man Who Never Read Novels”. Now, what category does this tale fall into? It was published in a horror magazine, but the events in the story could be interpreted two ways. It might, after all, be termed a mainstream tale with dark psychological undertones and touches of the fantastic. Or it might be straight horror. I’ll leave the reader to decide.

“Beauregard” is one of my favourite stories in this collection. The eponymous central character of this tale is an amalgam of two friends, sharing characteristics of both. While Beauregard is not a very nice person, I make no such claims for my friends. And while they are both beset by demons, they are psychological demons, rather than the type which hound Beauregard. This story was first published in

Dark Terrors 5

edited by

Steve Jones and David Sutton.

I have very little recollection of writing “Li Ketsuwan”, or the ideas behind it. It’s set partly in Thailand, where I’ve lived for a time, and unlike most of my stories features a wholly unlikable central character, and

is

overtly supernatural. “Li Ketsuwan” saw light of day in Andy’s Cox’s magazine

The Third Alternative

.

“Ghostwriting” was the second story I wrote for Robert Morrish at

Cemetery Dance

. It’s based on an idea I’d had kicking around in my head for years, ever since a friend demonstrated to me his PC’s voice recognition program. “Now,” I thought, “what if he were to leave the room with the program still running, and he came back to discover words on the screen?” I don’t know why the idea took years to turn itself into a story, but it did. Again, this one is an ostensible horror story that just might be interpreted as a psychological mainstream tale.

“Taipusan” had an interesting genesis. I wrote a vastly different version of this story as a science fiction tale in my

Fall of Tartarus

story cycle, about the planet of Tartarus and its sun which was in the process of going nova. The story didn’t work as SF, and didn’t fit into the cycle. I left it out, filed it away, and resurrected it years later. Over a long period I cut it to pieces, rewrote, cut and rewrote, excising scenes and characters and even a sub-plot. I also stripped every SF element from it and set the story not on Tartarus but in India in the late 1940s. It was the third of my tales to be published in

Cemetery Dance

.

“The Memory of Joy” is a bleak story of loss and grieving or, in the case of the mother in the story, of not grieving. It’s certainly a science fiction story, but also very definitely horror, to my mind. After all, what can be more horrifying than the death of a child? It was first published in Christopher Teague’s anthology

Choices

.

“The Disciples of Apollo” is the earliest story in this collection, written way back in 1988. This could be seen as a mainstream story right up until the very last, twist-in-the-tail line, which very definitely turns it into a horror story. It’s not often that I get ideas for kicker endings like this one, more’s the pity. It appeared in

Other Edens III

, edited by Chris Evans and the late and sadly missed Robert Holdstock. It was only the sixth tale I’d sold, and I treasure Rob’s acceptance letter in which he wrote: “And when I reached the end I leapt out of my chair and punched the air!”

“The House”, by contrast, is my most recent horror tale, this time for Jonathan Oliver at Solaris, where it appeared in the anthology

House of Fear

. It concerns another writer (I like writing about writers), and something that has cursed him for years and years, and how, at last, he is exorcised of that curse. Horror or mainstream? Again, I’ll leave you to decide.

I hope you find these pieces entertaining – and I hope I can muster another collection of horror tales before another quarter century has passed.

Eric Brown

Dunbar

January, 2012

The Man Who Never Read Novels

Simon Russell met the Man Who Never Read Novels on the train from York to London. It was a bitingly cold day in February and he was due to deliver his latest novel, a suspense thriller entitled

The Devil Takes All

, to his publisher. He thought it the best of his dozen novels to date, the book which, despite its title, he hoped would bring an end to his being categorised as a horror novelist. It was about a man who, when confronted with a series of supposedly occult events, works gradually towards a rational conclusion.

Russell himself was a rationalist, a man for whom there was always a scientific explanation. And if some phenomenon could not be explained scientifically, then it would be only a matter of time before science came up with the answer.

Carstairs, his editor, often laughed at the paradox that a man of Russell’s unbending materialism should make a living from writing horror stories. Russell, somewhat shamefacedly, defended himself by saying that he had started in the genre as a young man in the ’Eighties, when he had been impecunious and impressionable,

and needs must when the Devil drives

...

But with this novel, he told himself as he boarded the train, he would break the mould.

~

The carriage was almost deserted. He took a window seat and, as the train rolled from the station, stared out at the frozen river and the frost-shocked trees in the park.

He always looked forward to his London trips. He led a quiet life with his wife Fiona, a university lecturer; long hours alone at the keyboard during the day and calm evenings over leisurely dinners discussing their work. London was an opportunity to meet like-minded individuals and talk shop. He had booked into a comfortable hotel in Kings Cross, and tonight he would make his way to the Groucho club, where he was bound to know someone among the writers and editors who were members.

He opened the novel he was currently reading, an early Graham Greene, and settled back into his seat. The Greene was a much anticipated reward for having ploughed through the manuscript of a good friend, the thriller writer Edmund Perry. Edmund wrote what the media termed techno-thrillers, and while Russell liked the man very much, he found that the novels were too loaded with crass action sequences to make them enjoyable. This, however, seemed to be what a certain section of the public wanted these days, so Russell limited his criticism to faults of plot and characterisation. He had finished the Perry manuscript late last night, with a vast sigh that the labour was at last completed, and he looked forward to beginning Greene’s

Stamboul Train

aboard, appropriately enough, the 12.02 to Kings Cross.

At Leeds, a dozen passengers boarded the carriage and one of them seated himself across from Russell, who refrained from establishing eye contact and continued reading. He sincerely hoped that the man was not one of those people who considered a journey ill-spent if unable to chat to strangers about whatever superficial subject came to mind. While normally affable and willing to strike up conversations with total strangers, Russell considered certain pastimes sacrosanct: reading was one of those.

As the train pulled out of the station, his mobile went off. He had set it to vibrate, loathing its irritating, pre-loaded jingles, and he answered the summons with reluctance. He was always self-conscious when using the contraption. He felt the stranger’s gaze boring into him as he said: “Hello?”

“Simon. Edmund here. Hope I’m not interrupting anything. I was wondering if you’d got round to reading the latest...”

Russell’s heart sank as he explained that he had finished it last night and would write a report on the novel when he got back from London. He hoped Edmund didn’t want a blow by blow account of the book’s strengths – and failings – over the phone.

“You’ll be in London tonight? Excellent. I’m up to see some film people in the morning. How about a drink at the Groucho and something to eat later on?”

“That sounds like a good idea – but don’t quiz me about the book, okay? You’ll have to wait for the report.”

“That’s fine. Meet around eight?”

Russell agreed and cut the connection, cheered by the thought of meeting his friend. He returned to his book – Greene was expertly introducing the train’s many passengers – and settled himself for a long, enjoyable read.

“Excuse me,” said the man sitting opposite.

Russell looked up. “Yes?”

“I couldn’t help but notice that you’re reading one of the very few modern novels I myself have read.”

Russell stared at the man. “Is that so?”

He was taken aback by the contrast between the man’s obviously educated accent and well-heeled appearance, and the content of his admission. He was perhaps seventy, severely thin but in the full flush of health, and dressed in an old-fashioned pin-striped suit. Something about his face, though, his darting, pink-rimmed eyes and thin-lipped querulous mouth, suggested eccentricity.

Russell decided that he might chat to the man, after all.

“I read it back in ’91,” said the man. “Ashworth, by the way,” he went on, leaning forward and proffering his hand.

Russell shook the limp hand. It was ice-cold. “Russell. Simon Russell,” he said. “Ninety-one? That’s a while ago...”

“And sadly it was the last book by a living writer that I ever read,” Ashworth said.

“It was?” Russell was amazed.

“And before that,” the older man said, “I read just three modern novels.”

“

Three

?” Russell echoed, disbelieving.

“

The Old Man and the Sea

– by Hemingway,” he added, as if Russell was not aware who might have written the book. “That would be back in 1961.”

“And before that?” Russell asked, intrigued now.

The man shook his head, sadly, it seemed. “That would be way back in ’46 and ’47. I read two books:

The War of the Worlds

by H.G. Wells, and

The Hill of Dreams

by Arthur Machen.”

For a few seconds, Russell found himself at a loss for words. At last he said: “But you do

read

, don’t you? If not living authors, then the classics, the Victorians?” As he asked this, he wondered at the man’s odd reluctance to read

living

writers.

Ashworth’s hyphen-thin lips stretched in self-deprecating melancholy. “Oh, I read all the classics,” he said, “the Victorians, and earlier – but I honestly haven’t had the experience of enjoying contemporary fiction...”

Russell nodded, non-plussed, and stared from the window for a while at the snow-bound landscape. He thought of the years of joy that modern novels had given him, the worlds they had opened up, the vicarious experiences and insights gained.

“If you don’t mind me asking,” he began tentatively, “why is it that you don’t read living...?” He trailed off as he beheld his companion’s bleak expression.

Ashworth stared at him, as if considering something, and then shook his head. “No... I can’t begin to explain. You wouldn’t believe me, anyway.” And he resumed his brooding examination of the winter landscape.

Russell was about to return to his book when something occurred to him. He thought about the books Ashworth had mentioned, and

when

he had read them. There was a pattern there that was not immediately apparent... and then he had it.

“You said you read the Wells in ’46 and the Machen the following year? Then in ’61 the Hemingway, and the Greene in ’91?”

Ashworth was watching him, his expression non-committal. “That is correct.”

“I hope you don’t think this a rude question,” Russell said, “but why did you choose to read these books when their authors had died the very same year?” Why, he wanted to ask, was he compelled to read only

dead

writers?

Ashworth shook his head, as if at a loss to explain himself. Then he lay back his head against the rest and closed his eyes, taking deep breaths.

Russell watched the performance, wondering what his words had provoked.

“Are you alright?” he said.

“How did you work it out?” Ashworth asked, staring at him.

Russell shrugged. “I’m obsessive about authors’ lives,” he said. “I read all the biographies. I have a thing about dates. Call it a good memory.”

Ashworth looked stricken, but for the life of him Russell was unable to work out why. “I must admit,” he began, “that I don’t begin to understand why you should be put off from reading living—”

Something in the other man’s cold stare stopped him dead.

Ashworth said: “I have never told anyone, before now, of my reason for not reading living writers.”

Russell nodded, his throat dry, as Ashworth scrutinised him.

The old man went on: “I did not, as you say,

choose

to read the books of recently dead authors.”

“Then–?”

Ashworth returned his gaze to the frozen landscape, and continued speaking. “I left school when I was fifteen, in 1945, when I was apprenticed to an engineering firm in Leeds. I had been a poor scholar, and to my knowledge had never read a novel – not even at school. In 1946, in an effort perhaps to give myself the education in the arts that I so lacked, I decided to begin reading novels... I picked up Wells’

The War of the Worlds

on the recommendation of a workmate.” He paused, his eyes on the snow-covered fields, but his thoughts lost in the past.

“And?” Russell prompted.

He blinked. “I read the first few chapters very quickly, and enjoyed them, and a few hours later, on the wireless belonging to my landlady, I heard on the news that Wells had died.”

Russell’s nodded, wondering if there might be a story in this.

Ashworth went on: “I thought little of it at the time, merely remarking upon the coincidence to my landlady.”

Seconds elapsed. The train roared through the winter-still countryside. “And then?” Russell asked.

“I finished the Wells. I enjoyed it sufficiently to try another novel, but it was some time before I read an article about Machen’s

The Hill of Dreams

in a Sunday paper. That week I withdrew it from the local library. I read the first fifty or so pages, and then...” He stopped, his words catching in his throat.

Russell was aware of his heartbeat, while at the same time his mind was rationalising the old man’s experience as nothing more than coincidence.

Ashworth turned his head, staring directly at Russell. “The following morning I read in the paper that Machen had died the day before.” He paused, licked his lips. “I was scared, Mr Russell. I cannot begin to tell you how scared I was. I told no-one, frightened that they might think me mad. I kept my secret to myself and resolved, from then on, to read only dead authors.”

Russell opened his mouth, but thought twice about trying to convince Ashworth of his naivety. The old man continued: “I was badly affected, Mr Russell. I was very badly scared. I thought myself in possession of some terrible power... You cannot begin to imagine my fear and guilt.”

Ashworth took a long breath, gathering himself for the next part of his story. “I tried to put the past, and the experiences, from my memory. I applied myself to my work, finished my apprenticeship, and was taken on as an engineer by the same firm. I worked hard, and steadily gained promotion. The years passed. I married a wonderful woman – who fortunately had no interest in contemporary fiction. When I was thirty, in 1961, I thought back to 1946 and ’47, and what I’d experienced. I considered myself worldly-wise by now, and considered the reading of those books and the consequences as no more than unhappy coincidence.”

“So you read the Hemingway?”

“And within hours I heard on TV that Hemingway had shot himself.”

A silence came between the two men, notwithstanding the rhythmic drumming of the wheels on the track.

“And in 1991?” Russell said.

“I was foolish. I should have learned from the errors of the past and contented myself with the classics. I should have known what strange and singular power I possessed.”

“But you rationalised what had happened?” Russell suggested.

Ashworth nodded. “Thirty years had elapsed. I began to wonder if, perhaps subconsciously, I had heard about the deaths and only then read these books. I was fooling myself, of course. I

knew

what had happened. But God knows, I wanted to be rid of the curse.” He fell silent, and then said: “So, knowing full well what I was doing, and fearing the outcome more than you can imagine, I selected an author old and nearing the end of his life... and began reading

The Heart of the Matter

.”

“And how long after that–?” Russell began.

“That very afternoon I heard on the radio news that Greene had died in Switzerland.” He smiled bitterly. “From that day to this, I have read no work of fiction by a living author.”

Russell let the silence stretch, then said: “You do realise that what you experienced, though appalling, were nothing more than terrible coincidences?”

Ashworth glared at him. “

Four times

?” he said.

Russell went on: “Four times is nothing. Three of the writers you mentioned were old and nearing the end anyway.”

“And Hemingway?”

“He was profoundly depressed at the time, maybe even mentally unstable. Believe me, it was mere coincidence that you should have read these books when you did.”

“Coincidence? But

every

time? Can you imagine the effect it had on me?”

“And your superstition and fear would have been multiplied every time the appalling coincidence manifested itself.”

“I always wanted to believe it was coincidence. The rationalist in me truly wanted to believe that, but the frightened child in here...” He gestured vaguely towards his temple.

Russell leaned forward and laid a hand on Ashworth’s knee. “Think about it,” he said soothingly. “How could your reading of these novels result in the deaths of their authors, miles away? There could be no reason, no linkage, no cause and effect. The only rational, scientific explanation there could be is that it was coincidence.”

“Which is all very well in theory,” Ashworth said. “But impossible to prove...”

Russell let the words hang in the air. He thought for a while. “I don’t think so,” he said at last.