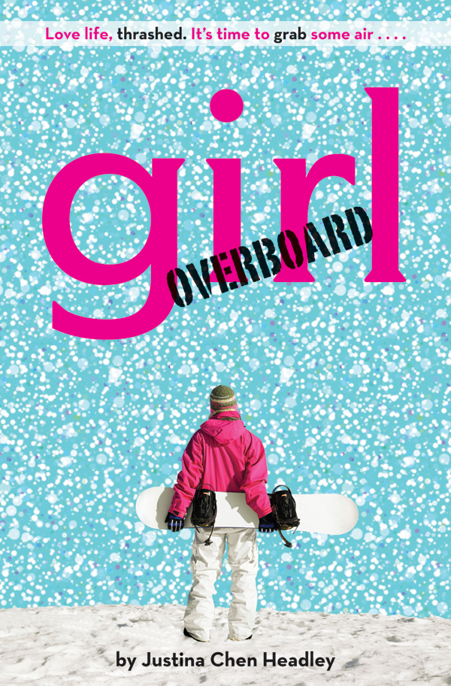

Girl Overboard

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For Robert, my man for all ages

If you were to ask me why I dwell among green mountains,

I should laugh silently; my soul is serene.

—Li Po (

A.D.

701–762), T’ang Dynasty poet

T

he worst part of

having it all is having to deal with it all—the good, the bad, and the just plain weird. Like seeing more of my dad when he’s on the cover of

BusinessWeek

than I do in person. Like the surgeon whose schedule was too jammed fixing professional ballplayers to deal with my busted-up knee… until he heard who my parents were, and miraculously his calendar was wide open. Like the pseudo-boyfriend who was more in love with my last name than with me.

So that full-body girdle waiting on my bed after school today? It doesn’t faze me at all. Not when I already know that the body I have isn’t the body Mama thinks I ought to have.

I ignore the corset and continue updating my manga-slash-journal as if the most important social event on Mama’s calendar isn’t starting. Whoever these guests are, they’re early birds who want to catch every last minute of Ethan Cheng’s birthday extravaganza. Not that I blame them. Considering that people still talk about my dad’s sixty-fifth blow-out bash five years ago like it was the party of the millennium, Mama’s inspiration at combining his seventieth along with Chinese New Year means tonight is sure to be a once-in-a-lifetime spectacle.

I flip to a blank page in my journal, draw Mama cattle-prodding my big butt with a jewel-encrusted chopstick down our marble stairs, and add her speech bubble—

“Aiya!”

cries my nanny, Bao-mu, barging into my bedroom without so much as a knock. Her slippers slap against her dry heels as she marches for me faster than you’d imagine a septuagenarian could move. “You suppose be downstairs.” When she sees that I’m still in the shapeless jeans that Mama hates, I earn two more

aiya

s and a distressed “You not ready!”

“I’ve got ten minutes,” I say confidently before I even nudge aside the silk curtains hanging from the canopy of my Ming-Dynasty bed and quick double-check the clock on my wall. “Actually, twelve.”

As though I don’t hear the doorbell ringing, Bao-mu tells me, “Guests here already.” Sighing impatiently, she takes matters into her own hands and plucks the journal out of mine. “Why you have draw now?”

“I just had to prepare,” I tell her honestly. Three hours of smiling and small-talking wipes me out more than a day riding the mountain. Or at least how I remember snowboarding before I tore my anterior cruciate ligament back in August.

Bao-mu nods as if she understands how I would need to fortify myself with some borrowed bravado, but that doesn’t stop her from ordering,

“Lai!”

and expecting me to follow. She forges ahead to my closet, the one place in this antique-laden bedroom where I can hang my snowboarding posters and ribbons from local riding contests, relics from my pre-Accident days.

Inside the closet I shed my jeans, sweatshirt, and bra to tackle the “gift” Mama so generously left me. What starts as a healthy glow turns to an all-out sweat usually seen only in hot yoga classes, as I struggle into this “Torso Bustshaping Bodyslip.” I suck in my stomach like, yeah, right, that’s going to help this lycra boa constrictor down my hips. It takes a full eight minutes of contortions never witnessed outside Cirque du Soleil before the bodyslip finally snaps across my thighs. According to my surgeon, at an inch over five feet and one hundred ten pounds—six pounds over my pre-Accident weight—I’m still smaller than the average American girl, which is why I’ll probably feel the pins in my reconstructed knee for the rest of my life. According to the Nordstrom lingerie department, I barely fill an A cup. Whatever the experts say, I challenge anyone to stand next to my mother and not become Sasquatch: huge, hulking, and with perpetual bad hair.

“Wah!”

says Bao-mu, admiring the miracle of microfiber with a light poke at my corseted tummy.

I’d

wah,

too, if my head didn’t feel like it’s floating away. I may have shed ten pounds in under ten minutes, but all I can manage are little hyperventilating pants. Tomorrow’s headline in the business section is going to read: CHENG DAUGHTER, 15, FOUND MUMMIFIED IN GIRDLE.

My smirk ends in a gasp. “I can’t breathe,” I tell Bao-mu.

“You get used to,” she assures me, although she looks awfully skeptical.

The voices downstairs recede into the living room. Hoping that fresh air might revive me, I hobble over to crack open a window. Below, one of the valets drives off to park a guest’s car. If my best friend Adrian were here, he’d identify the type of car just by the way its engine rumbles, but Age is probably still snowboarding on all the new powder at Alpental. This morning, he text-messaged me during History: “Fresh pow. Blow off school.”

“No can do,” I had surreptitiously messaged back, watching the rain through the classroom windows and imagining the snowflakes layering the mountain. But I couldn’t risk being late for Baba’s party. Besides, I still have my parents’ snowboarding embargo to deal with.

Chelsea Dillinger, It Girl of Viewridge Prep, barrels down our long driveway in her black Hummer. Even before the vehicle’s doors open, the shrill voices of the Chelsea clones, the girls I’ve dubbed The Six-Pack for all looking uncannily alike, shriek about

Attila,

the new teen flick premiering later tonight for the viewing pleasure of the “younger” set.

“Hurry,” urges Bao-mu, taking my hand in her wrinkled one and yanking me back to the closet.

It’s time for my showdown with the tiny yellow dress that Mama carted home from Hong Kong a couple of days ago. My nemesis of silk hangs like a piece of art in the center of my walk-in closet: a micromini halter dress so short it could pass for a sequined tank top, adorable on Mama, obscene on me. When I was little, I never played dress-up. Why bother when every day

was

dress-up? “She’s darling,” salespeople would coo at five-year-old me dolled up in outfits that coordinated with Mama’s, as if I was a purse or a pair of shoes.

Now, even with the super-suctioning power of the body shaper and Bao-mu’s

aiya

-ing, I struggle with the back zipper and catch myself in the floor-to-ceiling mirror that runs the entire back length of the closet.

“Oh, no!” I gasp, the words weak, horrified. Perhaps that was Mama’s intent all along: deprive me of oxygen so I won’t have the breath to complain about looking like an overstuffed potsticker.

“Ni zhen mei,”

says Bao-mu, eyeing me with pride as if she were my grandmother, one in desperate need of an eye exam if she really thinks I look beautiful with this sequined dragon, flapping wings and all, rising from my hip to my chest.

I turn to my side and correct myself. The dragon isn’t flying away; it’s being catapulted off the taut trampoline of my girdle. I’d fling myself onto my bed if I could, but in this vise, the chances of that happening are about as good as me sneaking off to catch some Friday night riding with Age.

I turn to my other side as if the view might be better. It’s not.

“I need take your picture,” says Bao-mu.

“No way. I can’t wear this,” I tell her, desperate. Downstairs, another doorbell rings and more hearty “good to see you’s” are exchanged. Nervous beads of sweat form on my nose, and I wipe them off. I should have tried on the dress Tuesday night after Mama handed it to me.

Bao-mu hurries to my bathroom and returns with concealer, still in shrink-wrap.

“Your mommy want you cover scars on your knee,” she says, urging the concealer on me, a makeup pusher.

I can’t formulate a single word, not even the two little letters that want to burst from my lips: N-O. No, I won’t wear this stupid dress. No, I won’t wear the heels. No, I won’t slather on makeup. No, I won’t hide the scars the way my parents want me to hide my snowboarding dreams.

“Hurry,” says Bao-mu as if she can hear my protests that she can do nothing about either, and flies out for her party duties.

Downstairs, Mama calls brightly to guests, lavishing them with her attention, “

Gong hay fat choy!

Happy New Year! Helen, you look brilliant.”

Alone in my bedroom, I stare at my pale face. Turning away, I rush over to my bedside table, grab my cell phone, and call Age, wherever he is, ready to beg him to come get me. Bring me to the mountains. To hell with my knee. And my parents.

“You know what to do,” Age’s voice rumbles before his voicemail beeps.

Another doorbell, another rash of greetings, another burst of laughter. You bet I know what I want to do. But what I have to do is non-negotiable. Missing a Chinese New Year celebration would be one thing, but my dad’s birthday bash? That’s impossible. I hang up without leaving a message.

Instead, I upturn the concealer and shake the brushed glass bottle until a drop wells on my finger like colorless blood. I bend down and work the thick, flesh-toned liquid over the red scars leftover from my knee surgery, rubbing until I look as good as new.

P

erma-smile in place,

I stand in the foyer where I’ve been commanded to stay until the very last guest arrives. The only guest I want to see is Age, but a glance at the grandfather clock—seven forty-five—has me sighing. If Age hasn’t shown up by now, he’s still snowboarding, which means the new powder’s so good, Age isn’t coming at all tonight.

My right knee throbs, calling into question Dr. Bradford’s pronouncement yesterday that I’m back to normal. This ache is not how I recall normal. No sooner do I perch on the bottom step of the staircase than the front doors bang open. I stand up hastily, wincing at the sharp jab in my knee, and then greet my older half-brother, “Wayne!”

All I rate from him is the barest nod of recognition that he reserves for acquaintances he can’t quite place. I, on the other hand, can place Wayne instantly, anywhere, any day. Dressed in a tailored double-breasted suit to elongate his slight build, Wayne’s the forty-five-year-old version of Baba, the right age to be my dad. Or my mom’s husband.

As usual, Wayne ignores me and strides toward Grace, my half-sister who’s standing near the pianist, offering a morsel of dumpling to the miniature poodle cradled in her skinny arms. As Grace laughs at whatever Wayne is saying, I retreat back to the foyer where no one can see how much I wish he would be the perfect big brother for me, too.

I lean against the altar table and rub my cheek muscles that deserve a gold medal for party-smiling. Even if I want to dump my hostessing duties, I can’t leave to sprawl on the red velvet couches in the theater downstairs with the rest of the kids, commiserate with the girls about being strangled by girdle. Anyway, which girl? And how far would I get before they started asking for something? Say, a personal tour of my closet. Or a joy ride in one of Baba’s sports cars. And then they’d snicker behind my back about how I was showing off again.

Over by the bar, a man bloated with self-importance broadcasts to the entire party, “We’re about to remodel the garage at our cabin because, you know, we’ve got to have a place to store the boat.”

Be still my heaving stomach.

While I’m mentally retching, a waiter trots over with a tray of bite-sized crab cakes resting on porcelain spoons. “Miss Cheng, anything you need?”

Yeah,

I think, reaching for a spoon but stopping when ever-vigilant calorie police Mama shakes her head at me from across the living room before returning to her conversation.

Miss Cheng needs a one-way ticket out of Cheng-ri-La.