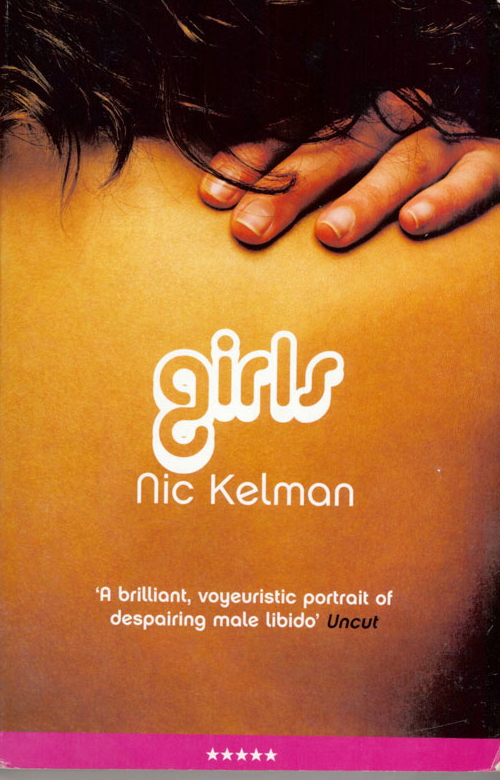

Girls

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library on request.

The right of Nic Kelman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright 2003 © by Nicholas L. Kelman

Excerpts from

The Illiad of Homer

by Richmond Lattimore.

Copyright © 1951 by The University of Chicago. Reprinted by permission of The University of Chicago Press.

Excerpts from

The Odyssey of Homer

by Richmond Lattimore.

Copyright © 1965 by Richmond Lattimore. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

Excerpt from ‘The Time of the Season’ reprinted by permission of Verulam Music Co. Ltd. Composer: Rod Argent

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, dead or alive, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com

First eBook Edition: September 2007

The Little, Brown and Company Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-316-02952-0

Contents

Nic Kelman

studied Brain and Cognitive at MIT. After spending a few years working in independent film, he attended Brown University on a full scholarship for his MFA in Creative Writing and where he was the James Assalty Prize for graduate fiction for

girls.

He now writes and teaches in New York City.

Not without M. & I.

. . . lacrimae volvuntur inanes.

. . .

the tears roll on, useless.

—

The Aeneid,

Virgil

What’s your name?

Who’s your daddy?

Is he rich like me?

Has he taken any time

To show you what you need to live?

— “Time of the Season,” The Zombies

Homer. From the Greek Hómâros:

“He who joins the song together.”

How did they get so young? These girls that only yesterday seemed so far away from us, these girls that seemed like another country. Tell me, when did they become children?

Children we want to indulge, to spoil. Children we will give anything to, everything. Except ourselves. Because, like a child, that is not something they desire. Like children, that is not something they will understand.

Yet unlike children, they make us tremble. Unlike children they can obliterate us with a glance. Just a glance. Or with their skin stretched so taut over every part of their body. With their flat bellies and unsupported breasts and bony ankles. With their, it must be said, “budding” lips because nothing is so much like a bud as the lips of a young girl, not even the buds themselves.

And when too did they cease to ignore us? When did they begin to fawn over us? When did we begin to fascinate them? With our money and companies and perceived security. When did we become the men that made us so jealous?

Perhaps you too will see her again. Perhaps on an ice field before a medieval stone church. Perhaps crossing a small piazza, empty but for you and her and a street vendor selling wet slices of coconut. Perhaps on a crowded subway, the stench of sweat and french fries and metal forcing you both to breathe through your mouths, to pant like animals. But not as you once did.

And it will be her that will recognize you, not you her. She will say your name with hesitation and a question mark. And you will continue to look at her dumbly for one more instant as you have been for minutes and then think, “No, it can’t be!” Yet you will say her name with pleasure. But not as you once did.

“My God,” she’ll say, “you’ve hardly changed!”

“And you look terrific too,” you’ll say. But that’s not what you’ll be thinking. You’ll be thinking how you never would have recognized her.

She doesn’t look bad, she’s only — what? — in her thirties after all. For her age, in fact, she looks excellent. If there are other men you will notice then how they are staring at her. If you are on a beach you will wonder then how, if the information was correct, after three children, she still manages to wear a bikini convincingly.

And yet you still never would have recognized her.

“Is that Chanel you’re wearing?” you will find yourself saying eventually, unable to stop, “I thought you hated Chanel — you always used to say it was. . . what was it?” and here you will find yourself pausing, then, as you actually say the word, smiling, openly mocking, the way you felt but never would have revealed when she used that same word so freely, so seriously, so long ago, “Bourgeois?”

“I don’t know,” she’ll say, shrugging, “I like it now.” And she will be embarrassed that you mentioned how she used to use that word. How she used to believe it meant something. Embarrassed. Even she recognizes she is not the same. But she believes it is because of something she has gained, not something she has lost.

You were in Pusan.

When you flew in, the port was hidden by cloud. You couldn’t see the city at all, only the tops of mountains. The man to the right of you, a Korean, said, “Ha! That’s smog. Smog! Not so pretty now, huh? Smog! Ha-ha! Ha-ha! Smog!” He went on laughing to himself as he picked up his paper again and read some more. You were still working for that investment bank, were there to find out why a container ship was behind schedule. You had been told it would probably be necessary to make an example of someone, that you should determine who.

And when you landed, it was drizzling, grey. The whole city was grey. Built of concrete and iron, built for building. You couldn’t see very far down the streets in that rain that was almost a mist. Through the haze the odd red or green punched — neons, traffic lights, trash-can fires. But that was all. On the way from the airport to the hotel and the next morning from the hotel to the office, you became completely disoriented. You tried to follow your route on the map your girlfriend had given you but it was useless. You didn’t know where you were.

At the office you spent a day going over the numbers, over the tonnage of materials brought in, over the daily costs of delay, over the percentage of the ship complete. The day after that you visited the ship itself. The fog had not cleared and when you stood near the command tower, you could not see the end of that unfinished deck. About halfway down it dissolved into a skeleton of girders which then itself dissolved into the mist. As if the mist were acid, as if the mist had halted construction.

And when you took the man off the job he yelled in Korean. In front of everyone he yelled at you in Korean. His face turned red, he was stocky, his stomach bulged against his belt, he threw back his shoulders, pointed his finger.

And you grew furious at him because he did not understand. This had nothing to do with him. Did he think he was playing a game here, that some conception of fairness applied? You picked up a phone to call security but he stormed out of the room. As you opened your mouth to say something to the others in the room, something about not caring, he opened the door again, yelled one last thing, and was gone. You remember thinking how puffy he looked as he stuck his torso through that gap, how the arms of his glasses splayed outwards as they ran back to his ears, remember wondering if it was the salty Korean diet that made him that way. It was only natural. You hadn’t understood a word he had said.

But when you left the building, when you got in that black car that somehow ferried you from the office to the hotel in Haeundae Beach, you noticed you were shaking.

And as you shaved before dinner, looked in the mirror, you grew angry at him again, angry at him for making you feel that way, for making you feel ashamed that you did not feel ashamed. “I mean, what the fuck does he think?” you said, waving your wet razor at your own face, half-hidden in lather. “He can have the benefits without the liability?” “Screw him,” you said.

The local office people took you to a vegetarian restaurant. “I don’t really like vegetarian,” you said but the meal was actually quite satisfying. Everything was fried and you had a lot of soju.

And when you got back to the hotel, the carpet outside your room was wet.

You had no way of knowing it was because he had been there. No way of knowing he had been too ashamed to go home to his wife and so had wandered in the rain for hours before finally sitting outside your door hoping to appeal to you. No way of knowing he had only just given up, only just decided that what he was doing was ridiculous, only just taken the stairs down as you took the elevator up. You fumbled with the card lock momentarily. As you closed the door behind you, the smell of the wet carpet was overpowering.

You are in Pusan.

You sit on the edge of your bed, drunk. You want to lie down but you can’t, you feel sick when you do. Somehow your eyes find the clock. It is only 10

P.M

., your girlfriend will just be getting in to work. She is a graphic designer. You pick up the phone, you call her on the company calling card.

“Hey babe!” she says, happy to hear from you. “So how is it? How’s it going?”

You open your mouth but you don’t know what to say. You think you may want absolution so you tell her what happened today, leaving out the part about the wet carpet, the part you don’t know. But when she gives it to you, tells you you did what you had to do, you realize that wasn’t it at all. You didn’t want her to tell you you did the right thing, you didn’t care if she thought you did the right thing or not because you already knew you did, you just wanted her to say, “I know what that’s like.”

But of course, she can’t say that, will never say that. And if she ever could then you could no longer be with her. Then you would both be tired. Then she would be a better friend, but a worse lover.

You haven’t been listening to what she’s been saying. You have been thinking. But as you open your mouth to say, “Listen, do you think I should be doing something else? Something I enjoyed a little more?” you decipher the sounds she has been making.

She has been telling you how she finally used that spa certificate you gave her for her birthday, the one you could afford to buy because last year’s bonus was so huge it paid off your college debt. She has been telling you how she went there for the full day and how they pampered her and how they rejuvenated her and how she felt so good afterwards, like a new woman afterwards.

There is a pause. She says, “Were you about to say something?”

“No,” you say, trying to sound surprised.

“Oh,” she says, “it sounded like you were about to say something.” And you wonder how that could be because you’re certain you didn’t make any sound at all.

“Anyway, listen, babe,” she continues, “I have to go — I have a meeting — but when you get back Mommy will make baby feel all better — she pwomises, OK?”

“OK,” you say, chuckling. But you don’t feel any better after you hang up. Just like you didn’t need her to tell you you did the right thing, you also didn’t need that. Mommies are for sick little boys. You aren’t sick, you aren’t a little boy, you don’t need sympathy. There is nothing tender loving care could do for you right now, right now there is nothing even your real mother could do to make you feel better. She wouldn’t, couldn’t, understand what it was like any more than your girlfriend.

The headspin subsiding but not gone, you turn on the TV. There is a channel that shows only Go, twenty-four hours a day nothing but Go. This really is a different place. You change into a bathrobe, you flip through some channels. There is a channel that has some kind of beauty contest. You watch it for a few minutes and realize it’s actually a talent competition. You try to masturbate a little but it’s no good, you’re not interested, it’s not enough.

You turn out the lights. You get in bed. But you can’t sleep. The Korean girls in the talent competition keep coming to mind, you can’t get the Korean girls in the talent competition out of your head.

Then you remember the card. After he had told you he was sending you to Pusan, after he had told you it might be necessary to make an example of someone, your boss had looked around, had made sure there were no female employees nearby, and had said, “. . . and if you get bored, they have the best fucking hookers in all of Korea there.” Then he had taken out one of his business cards and written a name on the back, the name of the concierge at the hotel to ask for, the one who’d “take care of you.” “Come on, Saswat,” you’d said, “you know I have a girlfriend!” “Yeah,” he said, “I know,” and tucked the card in your breast pocket.

You turn on the light again. Naked, you find the suit and pull out the card. You sit on the edge of the bed turning it over and over with your fingertips. You study the printed name of your boss and the Korean name written on the other side, written with a $1,200 pen. So many things run through your head. It’s not really any different than masturbating, is it? I wouldn’t tell her I jerked off, would I? At last you decide you’ll call down and see how much it costs. Just out of curiosity.