GodPretty in the Tobacco Field (28 page)

Read GodPretty in the Tobacco Field Online

Authors: Kim Michele Richardson

Six Years Later

I

'd found him.

'd found him.

Or maybe it was Freddy who found

us

.

us

.

“

Howdy, pretty lady . . . Howdy, howdy, soldier,

” the big wooden doll called out.

Howdy, pretty lady . . . Howdy, howdy, soldier,

” the big wooden doll called out.

Twinkly lights painted the summer evening skies. The Kentucky State Fair bustled with all kinds of folks from all over the Commonwealth, its last night pleated with scents of tired cooking oil, stale popcorn, and spent sparkle.

We'd been bringing our twins here every year for the last three. Our daughters insisted on visiting Freddy as soon as we arrived and before we left, calling out their excited good mornings and blowing sleepy good-night kisses to him.

Gunnar'd even bought us one of those fancy Polaroid cameras to mark our visits, saying, “The Sheriff of Nameless and his family deserve a fine camera!”

I watched Bur and Gunnar carry the twins over to the balloon vendor across from Freddy. The four of them like that put a smile on my face.

Baby Jane set her cage down beside me and handed me the prize money to put back for her college. I slipped her winner's check into my purse. Excited, she wagged the shiny ribbon in front of me, waiting.

For the third year in a row I pinned the ribbon onto her Future Farmers of America jacket. Baby Jane caught my hand and squeezed, then smoothed down the purple streamers draped over the locket beneath it. I'd given her the silver locket on her sixteenth birthday, tucking inside one of the slots my sketching of the basket that I had plucked off the tobaccos that long-ago day. Baby Jane'd saved part of that old fortune-teller, too, and placed my drawing of the hen alongside it.

She kissed my cheek and hurried over to the balloon vendor to show off her award, turning heads with her bright smile and the same Siren-calling hips of her older sister Henny. Baby Jane's Grand Champion hen called after her, fussing in soft, rolling clucks.

Two teenagers strolled past, slapping Rose's musical wooden spoons against their palms. They hummed “Black Jack Davey,” the song Rose taught folks to go along with their new spoons.

I tapped my foot remembering how we'd sung it in the parking lot till Crockett'd showed up. . . . At first I worried about coming back to the fair until Rose said Cash Crockett had gotten into trouble after I'd left. “They caught him in a storage barn with a thirteen-year-old 4-H girl and fired himâsent him to the city can for a while, too.”

I smoothed down the day's wrinkles that puckered my old strawberry dress that Bur always teased me about. He'd laugh. “You've been wearing that old dress every year for this fair, sugarâdone wore off the creases even.... How 'bout I buy ya a new one from the mail-order catalog?”

A quivering wind kicked up. I covered the two flapping ribbons pinned to my chest that I had won for this year's art exhibit. I'd already sold the illustrations to a book publisher in New York. A few years back, one of their businessmen had been traveling down our way and spotted my art at Zachery's in Tennessee. He'd taken a fancy, using them for a hotshot author's book covers.

The burst of air calmed. Resting my tanned hands on Freddy's white picket fence, I soaked up the night breeze.

Then he walked up alongside the small crowded fence, tall-dark-handsome as a mountain shadow over flower root. Looking smart and straight ahead at Freddy he was all decked out in a pressed uniform, polished black shoes, shiny belt buckle, and his garrison cap angled just right.

He hadn't come back to Nameless. Not once. He'd not written to me either after that long-ago good-bye letter I'd posted to him. Though he'd been sending letters and money to his mama, regular-like. She'd go off to visit him once in a great while but kept tight-lipped mostly, saying he had made the army his career.

Myself, I didn't get away from the fields much, except for this fair, and maybe once a year to see Henny and her four kids over in Beauty. She'd call, begging a ride to the penitentiary so she could visit her man, and then over to the old state insane asylum to visit Ada.

He brushed against my elbow as he eased himself into the row of people.

My insides rattled, ears filled with a whooshingâsame as it did in the tobacco fields back then. I gripped the fence, a knowing banging my chest.

I was getting ready to slip away, when slowly,

a slow-talking-hands-slowly,

he stretched his pinky finger, hooked on to mine, and squeezed. Quietly, he stared up at Freddy.

a slow-talking-hands-slowly,

he stretched his pinky finger, hooked on to mine, and squeezed. Quietly, he stared up at Freddy.

I kept my eyes locked on Freddy, too, and lightly pressed back.

Soft and low, Rainey struck the words to “Sweet Kentucky Lady.” “ â

Honey, there's no use in sighing

. . .

Your eyes were not made for crying . . . Sweet Kentucky Lady . . . Just dry your little eyes

. . .

You're still my rose of Kentucky. No rose is sweeter to me . . .

' ”

Honey, there's no use in sighing

. . .

Your eyes were not made for crying . . . Sweet Kentucky Lady . . . Just dry your little eyes

. . .

You're still my rose of Kentucky. No rose is sweeter to me . . .

' ”

A small boy pushed up behind us, wound himself tight around Rainey's long legs. A pretty Asian lady leaned in between them, sweetened Rainey's cheek with a kiss.

“Daddy,

Daaa-dy!

” the boy shouted up at Rainey, tugging, smiling big as the moon. “Mama says it's time to tell Freddy good-bye! I don't wanna!”

Daaa-dy!

” the boy shouted up at Rainey, tugging, smiling big as the moon. “Mama says it's time to tell Freddy good-bye! I don't wanna!”

Rainey dropped his hold and lifted the little boy up. “Time to go, son.”

The boy shook his head. “I want to stay

forever,

Daddy,” he pouted, rubbing his sleepy eyes.

forever,

Daddy,” he pouted, rubbing his sleepy eyes.

“Hear, now.” Rainey hoisted his son a little higher. “We don't have to say good-bye, Gunnar. How 'bout we just say good night?” he coaxed, latching on to his son's pinky finger.

Little Gunnar grinned and clamped back, then hugged his daddy's neck.

Rainey pressed a kiss into his son's tiny black curls. Resting his head atop the boy's, Rainey's tender gaze fell to mine.

“Good night,” he said softly over his son's head and at me this time, and stretching his wiggling pinky.

Good night

Acknowledgments

Thank you bunches to Liz Michalski, Ann Hite, Danielle DeVore, and others who gave their valuable time, feedback, and suggestions during first drafts. Thank you, Mike Schellenberger and Homer Richardson.

Jamie Mason, thanks for being a wonderful writing friend. George Berger, thank you again for staying with me all the way.

Agents Stacy Testa and Susan Ginsburg, my wise and talented representatives and my biggest cheerleaders, you have my deepest gratitude forever.

To the folks at FoxTale Bookshop, in Atlanta, I'd be remiss if I bypassed your kindness and huge support. I love and thank you to the moon and back.

John Scognamiglio, you are the. very. best. an author can have, and I thank you for being so very good to me. To Kensington and its amazing team: Vida Engstrand, Paula Reedy, Kensington's amazing artists, and so many others behind my novels, I thank you for your dedication and endless hard workâalways, always, I am grateful and indebted to you.

Joe, I love you like salt loves meat. Son Jeremiah and daughter Sierra, I love you forever.

To you, wonderful reader: Thank you for inviting me into your home.

Please turn the page for an intimate conversation

with Kim Michele Richardson about

GodPretty in the Tobacco Field

.

with Kim Michele Richardson about

GodPretty in the Tobacco Field

.

GodPretty

is a phrase that I made up to show starkness in the brutal and beautiful land and its people and mysteries. The term is necessarily paternalistic in the book and means to the one character, Gunnar, to keep a good and Godly soul if you are of a religious nature as he is. To Gunnar,

GodPretty

is applicable to females, while a male would be “righteous.” Gunnar uses my coined phrase

GodPretty

to push his strict moral code on his fifteen-year-old niece, RubyLyn. It came out of the uncle's yearnings for his nieceâwanting her to be pretty and pretty in the eyes of the Lord, so God would protect her when he no longer could, so that she would have a good life and be smiled upon by others not only because she'd be pretty but because her soul would shine, too. From the opening scene you can feel the title, the contrast with the ugly tobacco fields, giving a foreboding presence. Gunnar controls RubyLyn with this phrase, his large presence, big hands, hard ways of talking, acting. So when he punishes her, she can't resist, can't fight, until one day . . .

is a phrase that I made up to show starkness in the brutal and beautiful land and its people and mysteries. The term is necessarily paternalistic in the book and means to the one character, Gunnar, to keep a good and Godly soul if you are of a religious nature as he is. To Gunnar,

GodPretty

is applicable to females, while a male would be “righteous.” Gunnar uses my coined phrase

GodPretty

to push his strict moral code on his fifteen-year-old niece, RubyLyn. It came out of the uncle's yearnings for his nieceâwanting her to be pretty and pretty in the eyes of the Lord, so God would protect her when he no longer could, so that she would have a good life and be smiled upon by others not only because she'd be pretty but because her soul would shine, too. From the opening scene you can feel the title, the contrast with the ugly tobacco fields, giving a foreboding presence. Gunnar controls RubyLyn with this phrase, his large presence, big hands, hard ways of talking, acting. So when he punishes her, she can't resist, can't fight, until one day . . .

I wanted to write a tale of tender love and loss, the importance of land, oppression of Appalachian women in the '60s, and use a unique place. More than anything it was my hope to weave the theme of poverty's oppression on women and portray the consequences. I do this with the four Stump girls, RubyLyn, and the rest of the women in the fictional town of Nameless, Kentucky. The girls' actions show how the crushing poverty knows no gender, age, or boundaries, and how it becomes a scatterbomb, harming the person, the family, friends, and everyone in larger societyâhow it affects learning, choices, and notions of self-worth on life's whole journey. And again, in

GodPretty

we visit racial strife and examine difficult history from this timely subject. We also look at the last public hanging that took place in Kentucky (Rainey Bethea, August 14, 1936, Owensboro, KY).

GodPretty

we visit racial strife and examine difficult history from this timely subject. We also look at the last public hanging that took place in Kentucky (Rainey Bethea, August 14, 1936, Owensboro, KY).

I hoped to explore Appalachia's history, back to when President Johnson and the First Lady, Lady Bird, surprised the world and visited the tiny eastern Kentucky town Inez in 1964. Bearing witness right down to the hand-hewn porch of Tom Fletcher that Johnson squatted on, to the color of the First Lady's coat, and to the reminder of the newly minted coin commemorating President Kennedy. I wanted the reader to feel that hope and loss through the eyes of a 10-year-old RubyLyn.

GodPretty in the Tobacco Field

is rich with music. I love music, particularly the violin. Though I can't play a lick, my daughter started playing strings when she was three, and my husband plays the clarinet and piano. And we have a set of simple hand-carved wooden musical spoons like those mentioned in the book.

is rich with music. I love music, particularly the violin. Though I can't play a lick, my daughter started playing strings when she was three, and my husband plays the clarinet and piano. And we have a set of simple hand-carved wooden musical spoons like those mentioned in the book.

The people of Appalachia are born to music, much of it still lost to time's passing, and I pull some lost treasures into the novel like this one I found from the National Jukebox in the Library of Congress: “Sweet Kentucky Lady” (

http://www.loc.gov/jukebox/recordings/detail/id/913

).

http://www.loc.gov/jukebox/recordings/detail/id/913

).

Art is important to RubyLyn, and the papers she uses for her fortune-tellers are made from the pulp of the tobacco stalk and have her intricate drawings of pastoral scenes, portraits, and her fantasy cityscapes.

The land is a vital theme, too. It is how we live, breathe. When I was young, I worked in a tobacco field one summer.

I hated it

. Now my family and I grow vegetables and fruit on our small farm to give to the elderly. But last summer I grew a tiny patch of tobacco to visit that childhood setting again for my characters.

I hated it

. Now my family and I grow vegetables and fruit on our small farm to give to the elderly. But last summer I grew a tiny patch of tobacco to visit that childhood setting again for my characters.

You'll visit a State Fair in the novel, icons of summer and youthâand look at the Future Farmers of America club before it allowed female membership, the sweeping change it made in 1969, and the important role the youth organization has for our earth and our future farmers.

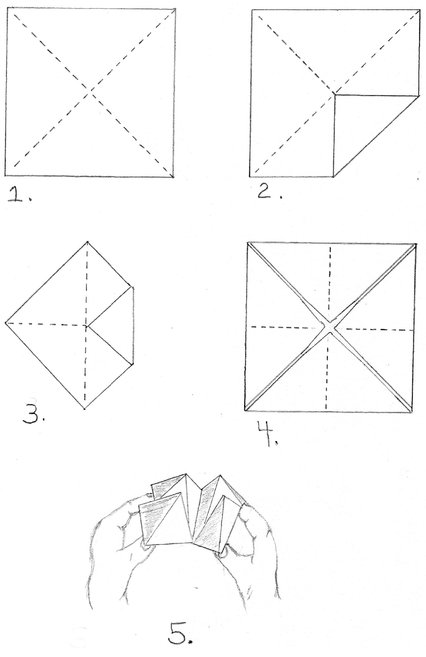

Making RubyLyn's Fortune-Teller

The paper RubyLyn uses for her fortune-tellers is made from the pulp of the tobacco stalk. She draws intricate scenes of rural life, portraits, and fantasy cityscapes. But you don't have to grow tobacco and produce your own pulp. You can have one by cutting out any piece of paper and following these simple instructions below. Decorate your fortune-teller any way you like.

To see other readers' fortune-tellers like the ones RubyLyn makes, please visit my Facebook page and post your photos:

I am excited to see your works of art!

Â

Â

INSTRUCTIONS

1.

Cut out square and fold over diagonally on both dotted lines.

Cut out square and fold over diagonally on both dotted lines.

2.

Flatten paper and fold all four corners to the center and press in creases.

Flatten paper and fold all four corners to the center and press in creases.

3.

Unfold, flip paper over, and fold four corners to center dotted lines.

Unfold, flip paper over, and fold four corners to center dotted lines.

4.

Fold vertically and then horizontally on dotted lines.

Fold vertically and then horizontally on dotted lines.

5.

Slip thumbs and forefingers into slots.

Slip thumbs and forefingers into slots.

A READING GROUP GUIDE

G

OD

P

RETTY IN THE

T

OBACCO

F

IELD

OD

P

RETTY IN THE

T

OBACCO

F

IELD

Â

Â

Kim Michele Richardson

ABOUT THIS GUIDE

Â

Â

The suggested questions are included

to enhance your group's reading of

Kim Michele Richardson's

GodPretty in the Tobacco Field.

to enhance your group's reading of

Kim Michele Richardson's

GodPretty in the Tobacco Field.

Other books

Ten Guilty Men (A DCI Morton Crime Novel Book 3) by Sean Campbell, Daniel Campbell

I’ll Become the Sea by Rebecca Rogers Maher

Size Matters by Stephanie Julian

The Madness of Mercury by Connie Di Marco

We Interrupt This Date by L.C. Evans

Don’t Bite the Messenger by Regan Summers

Semper Human by Ian Douglas

Anything For You by Sarah Mayberry

Arcanum by Simon Morden, Simon Morden